Freedom had its fighters and its financiers!

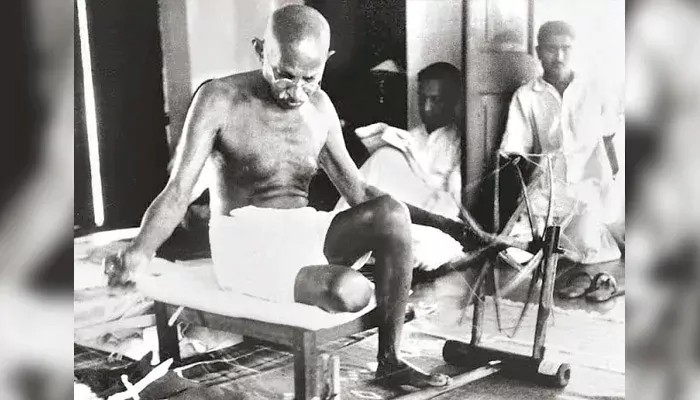

When we think of Gandhi, we picture a frail man in a khadi dhoti, walking miles with a stick. But there’s a lesser-known side to the story: the freedom struggle wasn’t just fought with salt and spinning wheels, it was also fuelled by bank accounts. Gandhi’s relentless campaigns, travels, and printing of literature needed massive amount of funds. And while the Mahatma never craved wealth, he knew the value of strategic support from those who had it.

The Maharaja of Darbhanga, Sir Rameshwar Singh, was no ordinary royal. While his palaces glittered with chandeliers, he understood that true prestige lay in contributing to the nation’s liberation. He discreetly financed several of Gandhi’s initiatives, from funding relief for indigo workers to supporting meetings and tours. His wealth gave Gandhi’s message the reach it needed in rural and urban Bihar, proving that a king could serve without a crown on his head.

Before "Tata" became a global corporate name, Sir Ratan Tata was using his fortune to drive social change. In 1912, he made a remarkable contribution to Gandhi’s cause in South Africa, supporting the struggle against racial discrimination. This early aid not only sustained the Mahatma’s campaigns abroad but also built trust between Indian industry and the nationalist movement. Ratan Tata believed in empowering movements quietly; leaving the limelight for the leaders on the frontlines.

If Gandhi had a capitalist soulmate, it was Jamnalal Bajaj. A successful industrialist from Wardha, Bajaj poured his profits into the freedom struggle. He didn’t just write cheques; he embraced Gandhi’s ideals, wore khadi, and actively participated in movements like the Salt March. Gandhi’s affection for Bajaj was so deep that he called him his “fifth son.” From funding ashrams to bankrolling civil disobedience campaigns, Bajaj proved that business and selflessness could share the same ledger.

Gandhi’s financial supporters were not limited to these three. Merchants, zamindars, and industrialists across India from textile magnates in Ahmedabad to trading families in Bombay kept the wheels of the movement turning. They funded newspapers that carried nationalist messages, underwrote Gandhi’s tours across provinces, and even supported the upkeep of his ashrams where strategies for Satyagraha were born.

Despite his simplicity, Gandhi was a practical person. He understood that even the purest ideals needed resources to travel. However, he accepted donations only if they came without strings attached. For him, money was always a tool. This approach built trust: the wealthy people could contribute without fearing political exploitation, and Gandhi could use the funds without compromising his moral compass.

Every telegram sent, every train ticket booked, every pamphlet printed for the cause had a cost. Without these patrons, Gandhi’s movements might have remained local whispers instead of nationwide roars. The unique combination of moral leadership and financial muscle was India’s quiet secret weapon, a partnership that history rarely acknowledges.

Today, corporate social responsibility (CSR) and philanthropic trusts in India draw inspiration from this era. The Tatas, Bajajs, and many other royal families still engage in nation-building projects, proving that wealth can be wielded with wisdom. Gandhi’s supporters may have stayed in the background, but their contributions were as vital as the marches that made history.

The freedom struggle was not a one-man mission; it was a symphony. Gandhi was the conductor, the people were the chorus, and in the wings stood a few quiet millionaires, ensuring the music never stopped.