As the emperor spent fortunes on the Taj Mahal, how were Agra’s ordinary people living and working?

When the Ambanis spend millions on a wedding, you can’t help but wonder. Just a few kilometers away, how are the people in Dharavi seeing it? If I were a daily wager earning Rs 700 a day, and I read that Rs 7 crore was spent on just one thing for that wedding, what would I feel? And it is not only about this one example. It is the Ambanis' money, and they have the right to spend it as they wish. But the contrast is indeed hard to ignore. A brand new Parliament House comes up while the poor keep getting poorer. Ironically, that Parliament House is built with the very poor's tax money and is said to be dedicated to the welfare of those people. Did anyone ask them if they would prefer this over a pothole-free road in their locality? Or when a massive statue is being built, does anyone ask the common people if they approve? No one cares. The powerful always decide, the powerless pay.

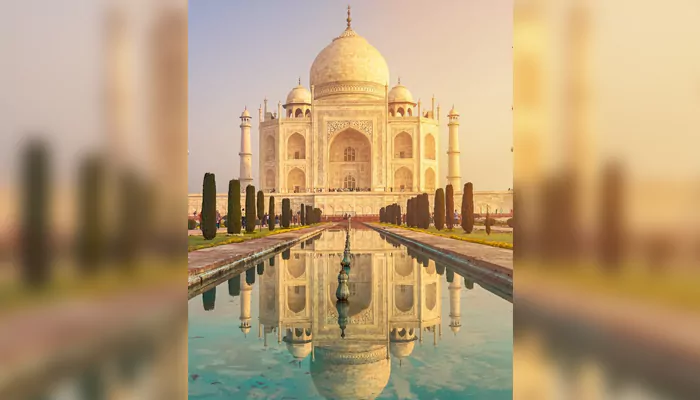

History, like the present, is mostly told from the view of those in power and not from those at the bottom. Which makes me wonder, what was life like for the common people in Agra when Shah Jahan was building the Taj Mahal? Well, I don't need to reiterate that the Taj is celebrated as a symbol of love and opulence. But for the people of Agra back then, it was also a massive personal project (remember, 'personal') funded by public money but not really meant for public benefit. So, in this story, we will explore research by historians and scholars to understand what those ordinary lives looked like while the emperor built his marble dream.

Shah Jahan reigned from 1628 to 1658, a period often described as the Mughal Empire’s golden moment. He returned the capital to Agra in 1628, placing the city at the heart of imperial politics and ceremony until he shifted to the new city of Shahjahanabad in 1648.

The Taj Mahal’s construction began in 1631-32, in the raw grief of Mumtaz’s death, and continued for roughly twenty years. Agra was already a city of palaces, markets, and pleasure gardens set along the Yamuna’s banks. Its economy rested on agriculture in the surrounding doab (the fertile land between the Ganges and Yamuna) and on the steady movement of goods and craftwork. But these decades were not untroubled. Famines struck, rebellions flared, and the wealth and splendor seen in courtly records sat uneasily alongside the fragility of rural life.

Shah Jahan with Prince Aurangzeb, one of the missing pages of the late Shah Jahan Album.

— Timurid-Mughal Archives (@Timurid_Mughal) December 6, 2021

Was this commissioned by Shah Jahan or by Aurangzeb after the war of succession? Aurangzeb looks magnificent, yet Shah Jahan is depicted taller with a larger halo. pic.twitter.com/raLi52xEF7

(Credit: Timurid-Mughal Archives)

The Taj Mahal was paid for out of the imperial treasury. In practice, that meant the harvests of farmers, the tolls on traders, and the steady trickle of duties from a thousand small transactions. Land revenue was the great engine of Mughal finance, with cultivators handing over a third to half of their produce, in grain or in cash.

The court chronicler Abdul Hamid Lahori wrote in the Padshahnama that construction began in 1632 and recorded its cost at 50 lakh rupees, though later historians suspect the figure was much higher. The money came from across the empire, but Agra’s surrounding districts, rich in wheat and millet, were among the most heavily assessed.

Travellers noticed the pressure. François Bernier, a French physician in India in the 1650s, observed that the land was treated as the sovereign’s property and that peasants, “driven to despair by so execrable a tyranny,” abandoned their fields. Taxes were not always levied gently. Revenue officials, the amils and zamindars, were notorious for squeezing more than their due. Even the river trade (indigo from Bayana, cotton cloth, sugar) contributed to the emperor’s projects.

Some later accounts speak of 32 million rupees spent on the Taj, though evidence points to staged payments over many years. What is clear is that the burden fell heaviest on cultivators. Historian Irfan Habib writes of “the cudgel and the whip,” compelling work for the benefit of others. In the villages near Agra, tax demands were calculated crop by crop, and even copper-coin levies could strip a household’s reserves.

At its height under Shah Jahan, Agra may have held more than half a million people. The wealthy lived in airy compounds with gardens and courtyards. The poor inhabited cramped mud-brick houses in mohallas divided by caste or craft, their walls softening in the monsoon and sometimes giving way under the Yamuna’s floods.

The bazaars were dense with sound and color. Bernier saw an “endless variety of things” on offer and entertainers (jugglers, snake charmers, etc.) competing for attention. Goods came in by river and road: bolts of cotton, jars of indigo, baskets of mangoes and melons.

Weavers, dyers, metalworkers, and masons filled the city’s karkhanas, or workshops. Some of their labor was for the open market, much of it for the court. Outside the city, farmers tended wheat, pulses, sugarcane, and other crops.

According to records, wages depended on skill and patronage. Akbar’s earlier Ain-i-Akbari still gave a rough guide: two or three copper dams a day for unskilled labour, twice that for masons, more again for specialists. A talented stonemason might earn well on imperial works, but those without connections often scraped by. As Bernier remarked, pay came “not according to the value of the labour” but to a patron’s whim.

Social boundaries were very rigid. Work often passed from father to son, and communities of different faiths lived close yet apart. Manucci, an Italian in the Mughal court, noted that elite women remained hidden from all men but their husbands, while poorer women laboured in the fields or carried goods to market. The Yamuna itself was a place of ritual as well as labour, its banks crowded during eclipses with worshippers waist-deep in the water.

Taj Mahal, located in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India. Commissioned by Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, built between 1632-1653 CE.

— Archaeo - Histories (@archeohistories) September 15, 2023

Pietra dura art-technique used to build Taj Mahal, consists of Floral or Calligraphic inlays. Inlay artwork of Taj Mahal is considered as Crown of Indian… pic.twitter.com/iJPpmMmF8T

(Credit: Archaeo - Histories)

Water quality, Bernier complained, left much to be desired. He described impurities “beyond my power of description”, a reminder that the city’s beauty coexisted with its squalor.

The Taj Mahal did not simply drain the countryside; it also drew people to the city. Court records speak of twenty thousand workers at the site, from master masons and inlay artists to carters and stonecutters. Craftsmen came from across the empire and beyond, their skills stitched into the marble with lapis, jasper, and onyx.

Whole neighbourhoods, such as Taj Ganj, grew to house those connected to the work. Skilled labourers could command high rates, and for a time, their families lived better than most. Historians note that the project drove demand for artisanship, pushing wages up for certain trades.

Yet the benefits were uneven. For every stone inlaid with precious gems, there was a family in the countryside whose taxes helped pay for it. In the 1630s, a famine in the Deccan brought hunger to millions, yet the building continued. Imperial spending on monuments did not pause for relief. Bernier wrote of peasants losing their children to slavery when debts mounted, a cruelty that speaks to the thin line between subsistence and ruin.

The Taj Mahal

— ART (@Art_For_Joy) July 14, 2025

Agra, India 🇮🇳

Time-lapse construction inside and out with a side by side view.

Inspired by @umesh_ai

Created using @Hailuo_AI 02#india #TajMahal #aiartist#photooftheday #minimaxai pic.twitter.com/vcQHjUftx9

(Credit: ART)

We hear little from the people themselves. Court records speak only the language of imperial grandeur. The Padshahnama celebrates the Taj as a wonder of the age, never hinting at resentment. Bernier, more candid, saw both the beauty and the tyranny: the domes and gardens on one hand, the “sheer necessity or blows from a cudgel” on the other. Manucci admired the monuments but could not ignore the gulf between Mughal luxury and the lives of the poor.

The Taj Mahal, without an iota of doubt, stands today as the supreme emblem of Mughal artistry. Tourists see symmetry and light, the play of shadow on marble, and more. However, only a few notice that its foundations are also the taxes, labour, and endurance of countless unnamed people. In its time, the monument created jobs, but it also deepened the pressures that defined ordinary life in Agra.

Well, the Taj’s beauty is unquestionable. So too is the truth that for many who lived in its shadow, it was not a love story, but another weight to bear.