The Boycott That Built a Nation: How Swadeshi Sparked India’s First Mass Awakening

- Sayan Guha

- 6 months ago

- 4 minutes read

Before Gandhi’s call for self-reliance, Bengal’s burning spirit laid the groundwork for India’s economic and political self-respect

It began not with a bang but with a thread.

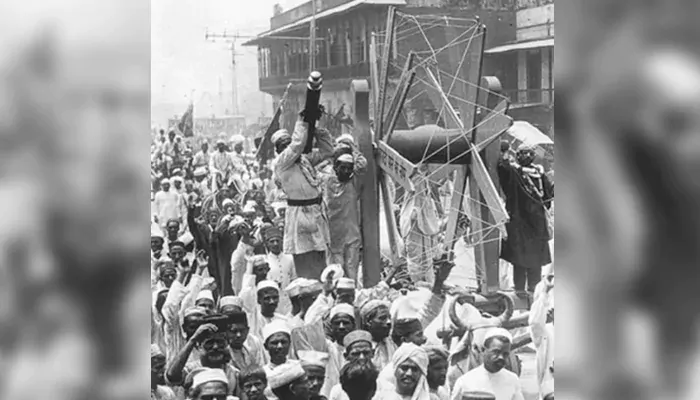

On a sweltering August day in 1905, Calcutta’s City Hall resonated with chants of "Bande Mataram" as a boycott resolution was passed. The focus? British-made goods — cloth from Manchester, salt from Liverpool. What followed was not just a protest against imported commodities but a revolution of the Indian spirit.

The Swadeshi and Boycott Movements began with defiance, not silence. At their heart was Bengal, a region wounded, divided, and angry.

The wound that bled fire

The Partition of Bengal in 1905 was more than just an administrative move. Ostensibly a move to improve governance, it was, in truth, a calculated colonial manoeuvre to divide and weaken. Lord Curzon's infamous maxim echoed this intent: “Bengal united is a power; Bengal divided will pull in several different ways."

With a single bureaucratic decision, Bengal was divided into East Bengal, with a Muslim majority, and West Bengal, with a Hindu majority. This act deeply hurt Indian unity.

But Bengal did not remain silent. It responded with a loud and determined voice.

(Credit: Cultural India )

The boycott becomes the battle cry

Calcutta responded swiftly. British salt and Manchester cloth were publicly burned. Shops selling foreign goods were boycotted, picketed, and even shut down. Volunteers, often teenage boys and young women, turned up in thousands to enforce the movement. For the first time, economics became a tool of resistance.

From Barisal to Bombay, the boycott quickly spread. The message was clear: If we must face hardship, let it be with dignity, using our own cloth, our own salt, and shaping our own future.

Swadeshi was not just a slogan — it was a strategy

The movement wasn’t merely anti-British; it was pro-India. Swadeshi, meaning "of one’s own country," encouraged Indians to develop indigenous industries — from textile mills to soap factories, matchsticks to banks.

Acharya P.C. Ray established chemical companies. Rabindranath Tagore wrote Amar Sonar Bangla, which would decades later inspire Bangladesh’s national anthem. National schools and colleges emerged across the country, rejecting colonial curricula and creating a parallel education system.

Above all, Swadeshi was a statement of confidence. It was a refusal to accept being seen as inferior.

(Credit: 99 Notes )

The first true mass movement

For the first time in Indian political history, the movement extended beyond the elite. Farmers, shopkeepers, artisans, women, and even children took part. Women stepped out of their homes, not just as spectators but as leaders of protest.

Volunteers’ corps called samitis emerged. Lokmanya Tilak used religious festivals to gather support in Maharashtra. Lajpat Rai and Ajit Singh mobilised Punjab. In the South, Chidambaram Pillai raised the Swadeshi flag high.

This was no longer just a Bengal issue. It had become India’s first coordinated act of mass resistance.

The fall — but not the end

By 1908, the British crackdown was intense. Leaders were imprisoned or exiled. The Congress split at Surat in 1907, weakening the political front. The movement’s momentum diminished under repression, and many pioneers withdrew.

But like many revolutions, its energy did not disappear. Instead, it continued quietly beneath the surface.

Swadeshi had sown the seed of Swaraj — self-rule — and awakened a political consciousness that no bullet could kill. Gandhi’s subsequent call for non-cooperation would draw directly from this foundation.

A legacy stitched into the nation's soul

The Swadeshi and Boycott Movements were not merely reactions to British policies — they were affirmations of dignity. They demonstrated to India that economic independence forms the foundation of political liberty.