When Gandhi’s peace met Britain’s Black Act head-on

It was April 6, 1919. Shops shuttered. Streets stood still. Silence echoed louder than slogans. Across Bombay, Calcutta, Delhi, and Ahmedabad, Indians observed a rare unity. They didn't gather with weapons. They didn't raise flags of violence. Instead, they joined in a hartal—a complete shutdown—against a law that shook the very core of civil liberty.

It was Gandhi's call. And India had answered.

What was this 'black act'?

The Rowlatt Act, passed in March 1919, was officially known as the Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act. But for millions of Indians, it was simply the Black Act. Why? Because it treated justice like a joke.

Under this law, anyone suspected of seditious activity could be imprisoned for two years—without trial, without a lawyer, without appeal. It gave the police sweeping powers to silence political dissent and suppress freedom of speech. In short, it made tyranny legal.

This was no wartime emergency regulation. The First World War had ended. Indians, who had fought and died for the British Empire, hoped for a gesture of gratitude. Instead, they were slapped with a law fit for a battlefield.

Credit: Bihar Ek Virasat

Gandhi strikes a match of resistance

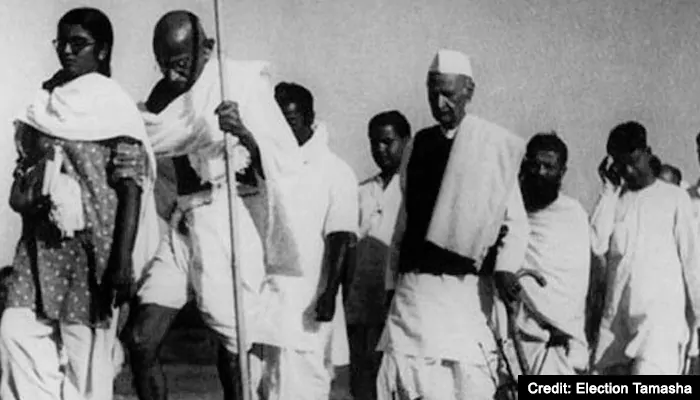

Mahatma Gandhi, once a firm believer in British justice, felt betrayed. After supporting Britain's war efforts and even encouraging Indians to enlist, he now saw clearly that the Empire had no intention of rewarding loyalty.

In February 1919, he formed the Satyagraha Sabha—a collective committed to peaceful resistance. It drew in young activists from the Home Rule League and Pan-Islamic circles. They pledged nonviolent opposition, even if it meant arrest or punishment.

When the bill became law, Gandhi called for a nationwide hartal. "Stop work, stop business, fast, pray, and protest," he urged. And on April 6, India did just that.

Credit: Exam Post

From satyagraha to savagery

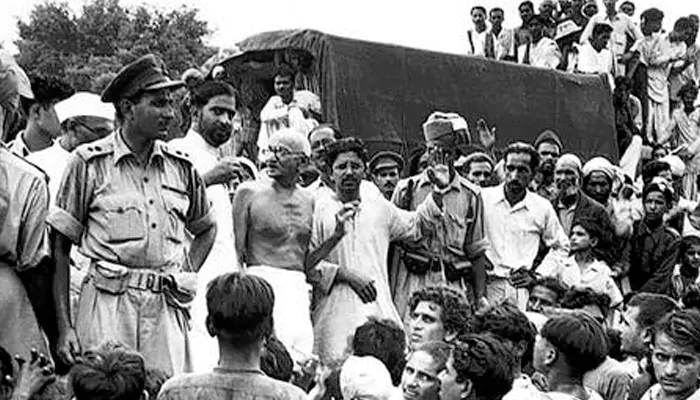

The hartal was meant to be peaceful. But the anger boiling under decades of colonial rule found other outlets. In cities like Delhi and Bombay, the protests turned violent. Railways were sabotaged. Police clashed with crowds. In Punjab, the situation spiralled.

In Amritsar, two respected Congress leaders—Dr. Satyapal and Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew were arrested without warning. Their detention sparked outrage. Protests erupted across the city. The British responded with unrelenting force.

On April 13, 1919, what followed was one of the darkest chapters in India's colonial history: the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. General Reginald Dyer ordered his troops to open fire on a peaceful gathering of men, women, and children trapped within the garden's narrow exits. Nearly 400 were killed. Thousands injured. India, devastated and disgusted, would never forget.

Why the movement mattered

Though Gandhi eventually called off the Rowlatt Satyagraha due to its violent turn, its symbolic power endured. For the first time, India rose as one—not just elites or activists, but shopkeepers, labourers, students, and clerks. Hindus and Muslims stood shoulder to shoulder, united by shared injustice.

It was also the first nationwide political awakening in colonial India. The idea that non-violence could confront imperial tyranny began to take root.

The limits of the struggle

However, the movement wasn't without flaws. Its reach was mainly urban. Villages—where most Indians lived—remained untouched. Rural communities still bore the brunt of colonial excess: arrests, beatings, censorship, and silent suffering.

And though the Rowlatt Act was eventually repealed in 1922, many similar laws remained on the books.

A tremor before the earthquake

The Rowlatt Satyagraha didn't bring independence. But it cracked the colonial edifice. It showed Indians that their collective voice had power. It made Britain uncomfortable. It set the stage for what would follow: Non-Cooperation, Civil Disobedience, and finally, Quit India.