From Oxford halls to Indian forests, Elwin walked away from the Empire to stand beside India’s Adivasis

Verrier Elwin’s life was one of rare crossings—of continents, of cultures, and of consciousness. Born in England and educated at Oxford, he arrived in India not to rule or reform, but to listen. He gave up a career in the Church to live among India’s tribal communities, challenging colonial prejudices with compassion and scholarship. Over the years, he became a champion of Adivasi rights, culture, and education—eventually even becoming an Indian citizen.

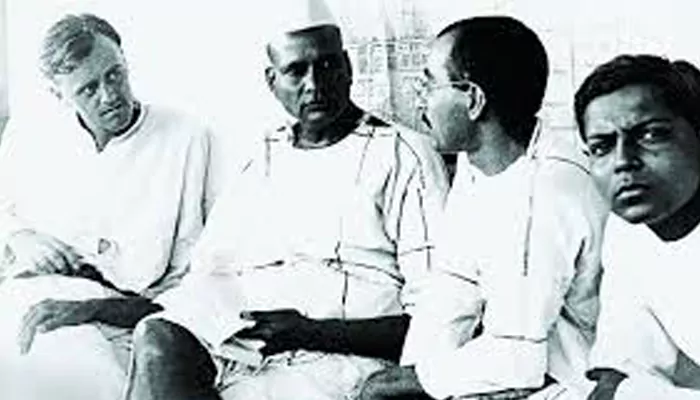

Born in 1902 in Dover, Elwin studied theology and literature at the University of Oxford. He was ordained as a priest and came to India in 1927 as a Christian missionary with the Christa Seva Sangh. But India changed him. He met Mahatma Gandhi in 1931, and his worldview underwent a significant shift. Elwin began questioning the moral certainties of his faith and the colonial order in which it was embedded. By the mid-1930s, he left the Church and renounced his missionary role. Instead, he began to focus on anthropology and joined India’s freedom struggle in his own quiet, academic way.

Elwin did not study Adivasis from a distance. He lived with them, first among the Gonds and Baigas in Central India. He immersed himself in their language, their songs, their rituals. He shared their food, walked their forests, and participated in their festivals. He believed they were not “primitive” but “different”—with social systems and spiritual worlds worth preserving. His books, like The Baiga (1939) and The Muria and Their Ghotul (1947) became foundational texts in Indian anthropology, written with rare intimacy and empathy.

In the British imagination, tribal communities were often seen as backward or uncivilized. Elwin challenged these views directly. He saw colonial policies as exploitative and deeply disrespectful of indigenous lifeways. He argued that tribal societies had their own wisdom—ones that should be protected, not erased. He opposed forced assimilation and defended the right of Adivasi communities to maintain their own identities. Elwin’s work was not just academic—it was political. He stood up for people the empire had long ignored.

After independence, Elwin became an Indian citizen in 1954. Prime Minister Nehru appointed him as the Adviser for Tribal Affairs in the North-East Frontier Agency (now Arunachal Pradesh). Elwin developed what became known as the “NEFA policy,” which emphasized cultural respect, limited outside interference, and gradual development based on consent. He believed in education but resisted the imposition of alien values. His approach influenced India’s early tribal welfare programs and left a lasting imprint on policy-making.

Apart from academic monographs, Elwin wrote poetry, essays, and memoirs. His autobiography, The Tribal World of Verrier Elwin (published posthumously in 1964), won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1965. He collected folktales, songs, and oral histories—creating a literary archive of cultures often overlooked. He also married a tribal woman, Leela, with whom he had children. While his personal life sparked debates, his commitment to tribal rights was never in doubt.

Verrier Elwin died in 1964, but his ideas continue to resonate. He was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1961 for his contributions to literature and education. His legacy lies in his insistence that progress must not come at the cost of dignity. Elwin believed education should empower, not erase identity. In a time when indigenous communities still face displacement and marginalization, his life offers a blueprint for engagement rooted in empathy.