He believed moral English education could cure the ills of superstition

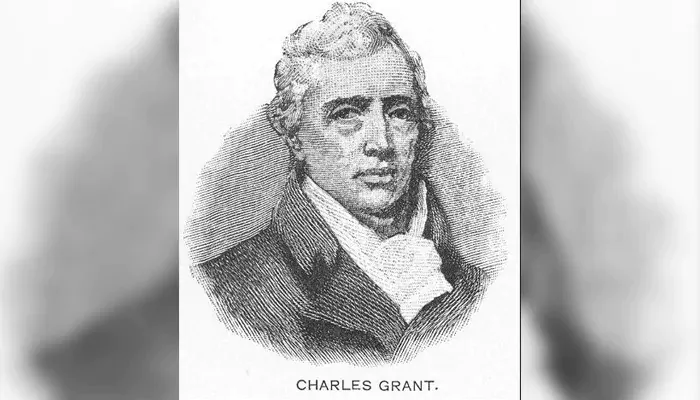

Charles Grant was not just another East India Company official. Behind his bureaucratic manner hid a deeply religious man who believed India could be transformed—not through conquest, but through education. For him, the real battle was not political but moral. It was a fight against what he saw as superstition, ritualism, and social decay. His weapon? English education rooted in Christian ethics.

Grant’s views didn’t arrive fully formed. He landed in India in 1767, during a time of famine and chaos in Bengal. Working as a civil servant, he witnessed the harsh consequences of both colonial misrule and local corruption. But it was personal tragedy—the deaths of his wife and child—that turned him inward. In grief, he turned to faith. Evangelical Christianity gave him purpose, and soon he began to see education as the path toward societal redemption.

Grant didn’t mince words in his writings. He believed that India was caught in a cycle of religious formalism and social stagnation. He argued that rituals had replaced reason and that moral values had been lost in the maze of tradition. In his influential 1792 manuscript, Observations on the State of Society among the Asiatic Subjects of Great Britain, Grant proposed that introducing Christian teachings and English education could rescue India from what he called “moral blindness.”

When Grant first presented his ideas to the East India Company, they were rejected. The directors feared that missionary activity and English education might provoke unrest. They labeled Grant’s proposals idealistic—even dangerous. But he didn’t give up. Over time, he found allies among Evangelical reformers in Britain, including William Wilberforce. With their backing, Grant’s ideas reached the British Parliament, slowly gaining traction.

Grant’s persistence paid off in 1813. When the East India Company’s charter came up for renewal, his ideas were incorporated into official policy. The revised charter allowed Christian missionaries to operate in India and, more importantly, sanctioned the promotion of English education. Though the language was cautious—described as a commitment to “moral and religious improvement”—the intent was clear. It was a quiet but major victory for Grant’s vision.

Back in England, Grant helped shape the East India Company College at Haileybury, training future civil servants in both administration and ethics. He also supported figures like Claudius Buchanan and Henry Martyn, evangelical chaplains who worked in India. His influence extended beyond policies to institutions that would educate generations of colonial administrators. Through them, the English-educated elite in India was born.

Grant’s legacy is not without contradictions. His call to replace traditional learning with English education was, in part, a civilizing mission deeply rooted in colonial ideology. He sought reform, but on British terms. Still, he was among the first to insist that true progress lay not in economic gain or political control, but in moral and intellectual upliftment. His belief that education could fight superstition shaped British policy in India for decades.

Charles Grant was a man of conviction. He believed that India’s future rested on a foundation of reason, morality, and Christian values. His approach may have reflected the paternalism of empire, but it also stemmed from a genuine desire to improve lives. At a time when rituals ruled and caste divided, Grant dared to say: educate first, reform will follow.