Let's understand the untold journey that shaped Babur before his conquest of India.

Babur came, saw, and won. In 1526, he defeated the mighty Sultan of Delhi at the Battle of Panipat, changing the course of the Indian subcontinent’s history. Many of the political, cultural, and even social threads we see today trace back to what he did back then. But while we all know the part where he arrived in India and founded the Mughal Empire, not many know the story before that chapter began. We’ve heard only bits, like he came from somewhere in Central Asia, he had royal blood, and he had ambition. But what was Babur really doing before India? How did a boy-king, barely a teenager, survive the loss of his kingdom, navigate betrayals, and fight his way through the rugged landscapes of Central Asia? And what shaped the man who would go on to become the first Mughal emperor?

This is the story before the story. Read ahead.

Babur was born on 14 February 1483 in Andijan, in the fertile Fergana Valley of present-day Uzbekistan. Through his father, Umar Shaikh Mirza II, he traced his bloodline to Timur. And through his mother, Qutlugh Nigar Khanum, he claimed descent from Genghis Khan. It was a noble inheritance, but was shadowed by the fracturing of the Timurid world into small, quarrelsome principalities.

When Babur was just 11, his father died in an accident, falling from a dovecote while tending pigeons. The boy inherited the throne of Fergana and, with it, the gaze of every ambitious neighbor. His uncles plotted, his own extended family schemed, and tribal loyalties shifted like sand. In these early years, Babur leaned on the counsel of his formidable grandmother, Aisan Daulat Begum.

Court intrigue, siege, and rebellion became his tutors. In the narrow valley between mountain ridges and river plains, he learned to read terrain, gauge loyalty, and make swift decisions under pressure.

To Babur, Samarkand was the heart of Timurid glory, rich in trade and power. In 1497, at the age of 15, he besieged and took it after a seven-month campaign. For a moment, he stood where Timur had stood. Then illness hit him hard, and while he convalesced, rebels claimed Fergana. Within months, both his hard-won city and his birthplace were gone.

He tried again. In 1500, he recaptured Samarkand, only to face the rising Uzbek leader, Muhammad Shaybani. At Sar-e Pol in 1501, Babur suffered defeat, sealing a peace by giving his sister, Khanzada, in marriage. The humiliation bit deep. He would later write in his memoirs of those years in Tashkent, “Much poverty and humiliation… no country, or hope of one.”

The failures taught him to value mobility over static defense and to scout the ground before battle. Also, they deepened his appetite for opportunity.

Shaybani’s Uzbeks were very relentless. Nomadic warriors from the northern steppes, they swept over the fractured Timurid lands. By 1501, Shaybani had forged the Khanate of Bukhara, and Babur was a prince without a country. He slipped away from battlefields, once hiding in a garden to escape capture.

From 1502 to 1504, he wandered between courts, often on the edge of hunger. These were years of survival rather than conquest, bargaining for allies and keeping his small band together. The great Timurid-Uzbek struggle was as much about identity as territory; the Persianate-Turkic culture of Babur’s line against the steppe traditions of the Uzbeks.

By 1504, the chessboard of Central Asia offered no winning moves. Babur turned south, crossing the Hindu Kush to seize Kabul from the Arghun ruler Mukim Beg. It was a prize within reach, weakly defended yet rich in orchards and trade routes.

Kabul gave Babur breathing room. He reformed tax collection, knit together Pashtuns, Tajiks, and Hazaras under his rule, and built an army drawn from many peoples. He laid gardens in the charbagh style, wrote poetry, and trained his troops in the mountain logistics that would later serve him well.

And it was from Kabul that he first tested India’s defenses, raiding across the passes in 1505. The idea of Hindustan had already taken root in his mind.

Beyond the mountains, Babur played a dangerous game with greater powers. In 1510, the Safavid ruler Shah Ismail I of Persia crushed Shaybani and sent his skull back as a grisly trophy. Babur allied with Ismail, even adopting Shia symbols despite being Sunni. With Persian aid, he briefly reclaimed Samarkand and Bukhara in 1511-1512.

But alliances are fragile. Religious tensions and local resentments turned against him. At Ghijduvan in 1512, the Uzbeks struck back, and Babur retreated to Kabul for good. He now understood the limits of borrowed power.

In his memoirs, Babur appears unvarnished. He loved wine and gardens, delighted in verse, and yet thrived on the gamble of siege and battle. Repeated defeats honed his tactics - quick marches, the clever use of terrain, the balance of cavalry with emerging artillery.

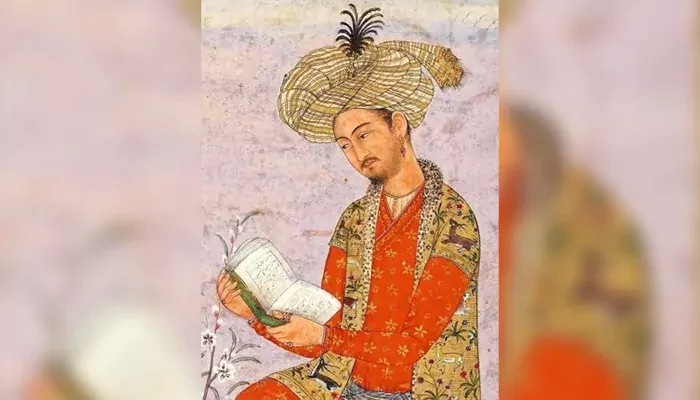

This book is a concise biography of Babur. Based primarily on his autobiography & existential verse, it chronicles the life & career of a Central Asian, Turco-Mongol Muslim who, driven from his homeland in 1504, ruled Kabul for two decades before invading 'Hindustan' in 1526. pic.twitter.com/QcWrPHqYZi

— Timurid-Mughal Archives (@Timurid_Mughal) July 10, 2020

(Credit: Timurid-Mughal Archives)

From Kabul, Babur pushed into Punjab. By 1519, his forces reached the Chenab River. India’s riches beckoned, and the Lodi Sultanate’s weakness made it vulnerable. After securing Kandahar in 1522, he gathered his strength. In 1525, he set out for Delhi.

At Panipat the next year, those years of loss, exile, and improvisation came to bear. Wagon fortifications, disciplined artillery, and a steady hand carried the day.

The Babur who entered India was not only a conqueror but also a survivor. The Mughal Empire he founded in 1526, blended the traditions of his Central Asian heritage with the cultures of the subcontinent, shaping politics, art, and architecture for centuries.