His efforts laid the foundation for women’s empowerment through learning

In 19th-century Bengal, the education of girls was almost unthinkable. Society resisted it, families feared it, and orthodoxy dismissed it. But one man—John Elliot Drinkwater Bethune—saw what others wouldn’t. Girls, he believed, deserved the same dignity of thought as boys. In 1849, with a small group of supporters and even fewer students, he laid the foundation of what would become the first formal school for girls in Asia.

Bethune wasn’t just an English educationist in colonial India—he was a reformer with a conscience. At a time when girls were denied books, his school in Kolkata opened a door that had long been shut.

It began modestly. The first school was set up in a borrowed house in Baitakkhana (present-day Bowbazar) with just 21 students. Bethune had powerful allies, including reformers such as Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Raja Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee, and Ramgopal Ghosh. Together, they navigated a society still bound by superstition and fear.

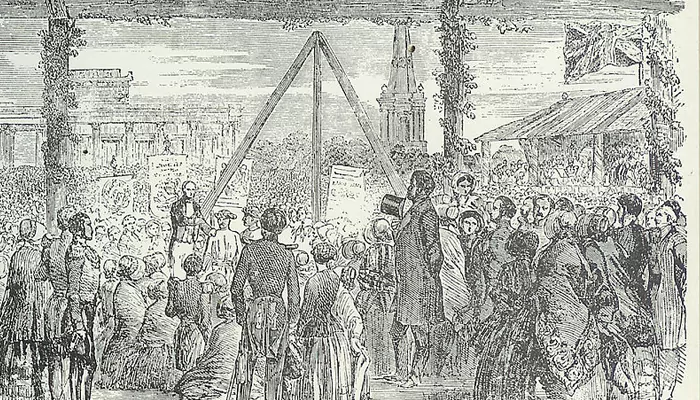

In 1850, a year after the school’s founding, the foundation stone for a permanent building was laid at Cornwallis Square. The school was called the Hindu Female School. Lady Littler, wife of the then Lieutenant Governor, planted an Ashoka tree on the premises—a gentle symbol of growth, endurance, and feminine grace.

Bethune died suddenly in 1851, barely two years after opening the school. But by then, his idea had already gained ground. His death, while tragic, didn’t stall the momentum. In 1856, the British government assumed control of the school. By 1862, it was renamed Bethune School in his memory.

The real turning point came in 1879. Bethune School transformed into Bethune College—the first women’s college in Asia. It had taken root. It had survived skepticism, resistance, and even the loss of its founder.

Bethune’s vision wasn’t limited to reading, writing, or arithmetic. His school was a space where young girls, many of them from conservative Bengali families, learned to think. They studied literature, languages, and crafts. But most importantly, they found their voice.

This was radical. These were not elite British girls—they were daughters of middle-class Bengalis, some of whom would go on to become writers, reformers, and freedom fighters.

Bethune knew that a sudden break with tradition would fail. So, he worked with the grain of society. His curriculum included Bengali, needlework, moral science, and a limited amount of English. It was just enough to encourage hesitant families to enroll their daughters, without causing backlash.

This balance was key. It was reform, not confrontation, but rather a dialogue. Bethune offered a middle path—between progress and tradition, between modernity and culture.

Bethune’s school soon became a model. Inspired by its success, reformers across Bengal began opening similar institutions. Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar himself would later spearhead the movement for girls’ education, drawing strength from Bethune’s early success.

The ripple effect was real. Bethune’s small school in Kolkata helped spark a broader change in how India viewed women’s education—not as a luxury, but as a necessity.

Today, Bethune College stands not just as an educational institution, but as a symbol. A symbol of courage in the face of tradition. A symbol of faith in the power of learning. And most of all, a symbol of what one man with conviction can set into motion.

John Bethune didn’t just open a school. He opened a future. A future where girls in India could aspire, achieve, and lead. And in doing so, he helped rewrite the story of education in the subcontinent—one girl at a time.