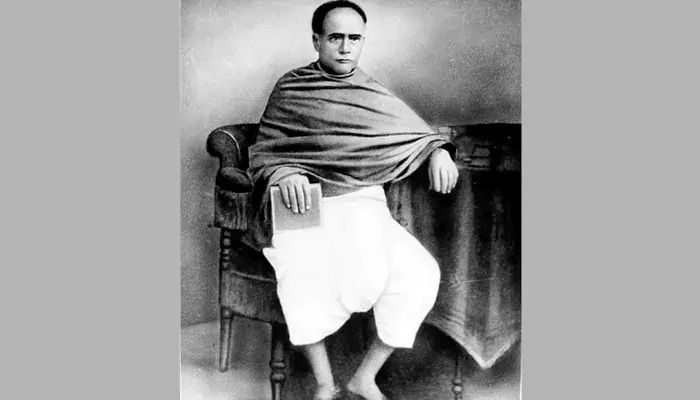

A reformer in dhoti, Vidyasagar defied 19th-century orthodoxy armed with reason, empathy, and a fountain pen

In colonial Bengal, social customs stood like stone walls. Women, especially widows, lived behind them—silenced, restricted, and shamed. Into this scene stepped Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, born in 1820 in the small village of Birsingha. A brilliant mind with an unshakable sense of justice, he chose not just to teach but to transform.

He was no firebrand or populist. He was a quiet revolutionary who transformed India through logic, literature, and a love for the oppressed.

Vidyasagar’s early years were marked by poverty. He studied under street lamps in Calcutta because his family couldn’t afford oil at home. But hardship sharpened his will. At Sanskrit College, he mastered grammar, logic, and philosophy—and earned the title "Vidyasagar" or "Ocean of Learning."

Later, as the Principal of the same college, he opened its doors to non-Brahmins and promoted the study of English and science alongside traditional texts. It wasn’t just about syllabi; it was about breaking social hierarchies through education.

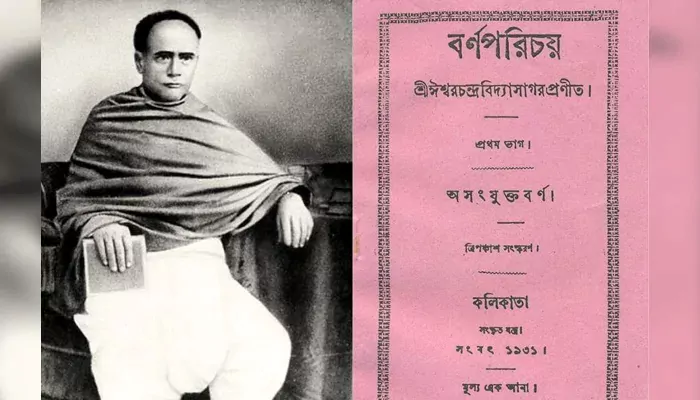

For Vidyasagar, language wasn’t just a tool—it was a weapon against ignorance. His Bengali primer Barnaparichay remains iconic. He simplified the script, refined punctuation, and made the alphabet learner-friendly.

Children across Bengal, regardless of caste or gender, could now pick up a book and read. Education became less about status and more about access. In a society stratified by privilege, that was a quiet revolution.

Few issues stirred Vidyasagar more than the plight of Hindu widows. Many were married off as children and widowed before adolescence. Tradition condemned them to a life of ritual mourning, often in poverty.

Vidyasagar took a bold step—he scoured ancient Hindu texts to prove that widow remarriage wasn’t unholy. With clear arguments rooted in scripture, he petitioned the British government in India. The Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act of 1856 was passed, largely due to his tireless lobbying.

He didn’t stop there. He personally arranged remarriages, offering moral and financial support to couples who had been shunned by society.

At a time when women’s education was viewed as a threat, Vidyasagar established over 30 girls’ schools across Bengal. He believed that an educated woman could nurture a better family, and by extension, a better nation.

He wrote textbooks, trained teachers, and even funded schools from his own pocket. This was not charity. It was an investment in the country’s soul.

Each girl who stepped into a school was, in Vidyasagar’s eyes, a step forward for India.

Though influenced by Western rationalism, Vidyasagar remained deeply rooted in Indian culture. He translated classics like Shakuntala and Meghaduta into Bengali and wrote essays that blended tradition with reform.

His critiques of polygamy and child marriage weren’t about imitating the West; they were about protecting dignity. He fought for the kind of India where tradition didn’t mean tyranny.

To many, he was “Dayar Sagar”—Ocean of Kindness. He combined intellect with compassion in a way few reformers did.

Vidyasagar died in 1891, but his work lives on in schoolbooks, street names, and public memory. More importantly, it lives in the lives of countless women who now read, write, and remarry without stigma.

He wasn’t a rabble-rouser. He didn’t lead rallies. But he changed laws, rewrote scripts, and rebuilt minds—one lesson, one student, one widow at a time.

In a nation still grappling with tradition and change, Vidyasagar remains a timeless guide.