Bhagvat Singh modernised his state—without ever kneeling to the Empire

In 1869, at the tender age of four, Bhagvat Singh became the Maharaja of Gondal, a small princely state in western India. Most child rulers were expected to be mere symbols. But Bhagvat Singh defied that script early on. With guidance from British-appointed regents and a solid foundation at Rajkumar College in Rajkot, he absorbed both tradition and reformist ideas. His quest for knowledge would take him far—eventually all the way to the University of Edinburgh. He wasn’t just royalty. He was also a scholar, physician, and reformer.

Bhagvat Singh wasn’t content being just another ruler in ceremonial robes. In 1887, he travelled to the UK to study medicine—a rare step for any Indian at the time, let alone a king. He earned his M.B. and C.M. degrees by 1892, followed by an M.D. in 1895. He became a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, the first Indian royal to hold this distinction.

But after his studies, he chose not to remain abroad. Driven by a vision for his homeland, he returned to Gondal, equipped with knowledge—and intent on transformation. His journey from Edinburgh back to India marked the beginning of a sweeping change.

As ruler, Bhagvat Singh launched sweeping reforms. Gondal became a laboratory of modern governance. He abolished many forms of taxation, introduced village-level self-government, and ensured proper sanitation and clean drinking water.

He was ahead of his time in advocating for women’s rights. Education for girls became compulsory under his rule. He removed purdah restrictions in royal spaces and encouraged women to work and study. Gondal became one of the first Indian states to promote gender equality in public life.

Electricity came early to Gondal. So did railways. Even telephones were installed while other parts of India lagged far behind. His court promoted science, literature, and the development of regional languages.

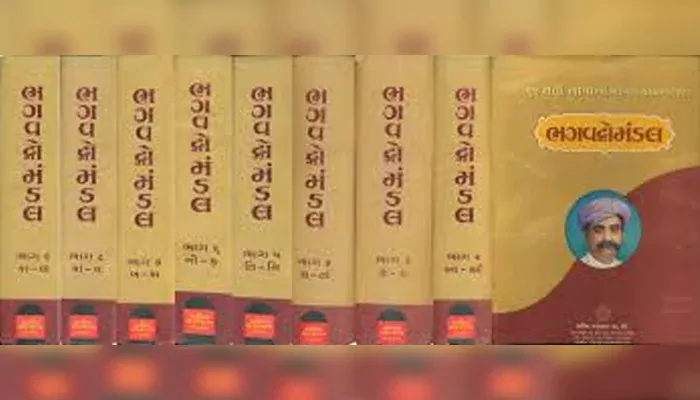

Bhagvat Singh didn’t just govern. He wrote, translated, and sponsored scholarship. One of his most celebrated contributions was the Bhagavad Gomandal, a massive encyclopedic dictionary in Gujarati. It was more than a lexicon—it was a cultural project aimed at preserving the richness of local language and heritage.

He also funded publications on medicine, law, and education. His palace housed a sprawling library. Knowledge, he believed, was power—and it belonged to everyone.

For all his accomplishments, the British were eager to reward Bhagvat Singh with honours. He received several medals and was appointed a Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire (GCIE). Yet, when he was considered for the even higher distinction of the Knight Grand Commander of the Star of India (GCSI), something changed.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Bhagvat Singh quietly rejected further titles. He didn’t announce a dramatic refusal. He let it be known—he had no interest in more imperial decorations.

In an age when princely prestige was often measured by the number of British honours received, Bhagvat Singh stood apart. His legacy, he felt, didn’t need a stamp of British approval. Gondal’s progress was proof enough.

Bhagvat Singh ruled for 75 years—an era that saw India transform under colonial rule and then rise towards freedom. When he died in 1944, Gondal was recognised as one of the best-administered states in British India.

But what set him apart wasn’t just what he built—it was what he refused. He believed a ruler’s legitimacy came from service to his people, not from imperial medals. He modernised without compromising his values.

In history’s long list of kings and courtiers who curried favour with the British Raj, Bhagvat Singh offers a rare and dignified counterpoint. Here was a man who studied abroad but brought change at home. Who earned degrees and honours—but walked away from the Empire’s highest title.

He proved that reform did not require submission. That dignity, especially for a ruler, lies in refusing to kneel. The Gondal King may have declined knighthood, but he earned something greater—respect, then and now.