From Miniatures to Masterpieces: Europe’s Surprise Role in Mughal Art

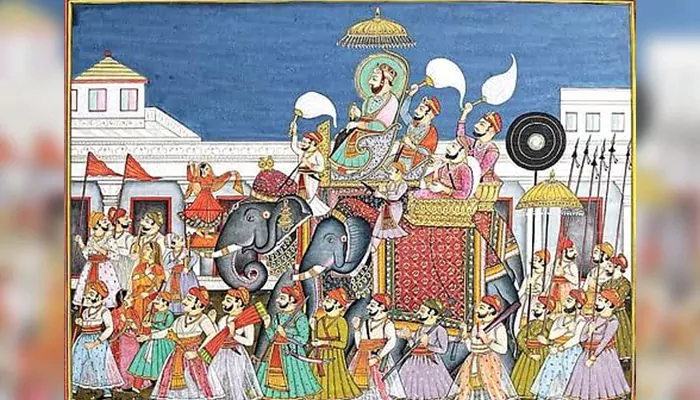

Ever noticed a blue-eyed man or an angel with curly blonde hair in a Mughal miniature painting? That’s not a mistake, it’s Europe leaving its artistic fingerprint. Long before globalisation became a buzzword, Mughal painters had already embraced it on their canvas. Behind the grandeur of floral borders, imperial hunts, and elaborate court scenes lies a fascinating artistic amalgamation between East and West. Welcome to the world of Mughal paintings, where Jesuit priests stood next to Mughal emperors, and European shading techniques flirted with Indian brushstrokes.

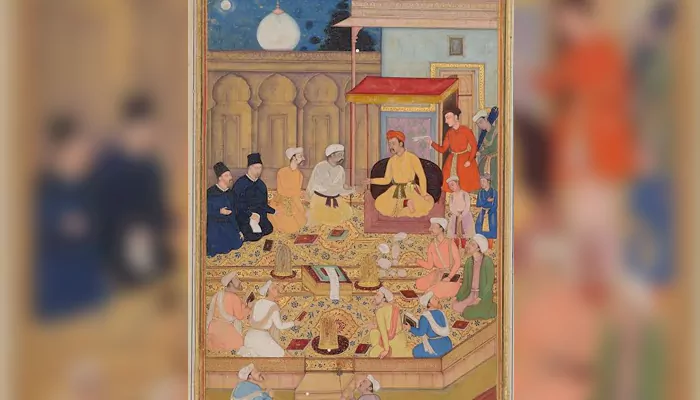

Let’s rewind to the 16th century. The Mughal Empire was booming culturally, politically, and artistically. But unlike what many believe, Mughal art didn’t evolve in isolation. When Emperor Akbar invited Jesuit missionaries from Europe to his court in Fatehpur Sikri, he wasn’t just interested in religion. He wanted books, paintings, and stories; essentially, Europe’s greatest hits.

These missionaries eventually brought illustrated Bibles, religious icons, and portraits that blew the minds of Indian artists. Once used to the flat perspectives of Persian miniature style, Mughal painters suddenly found themselves staring at images with shadows, proportions, and perspective - fancy stuff!

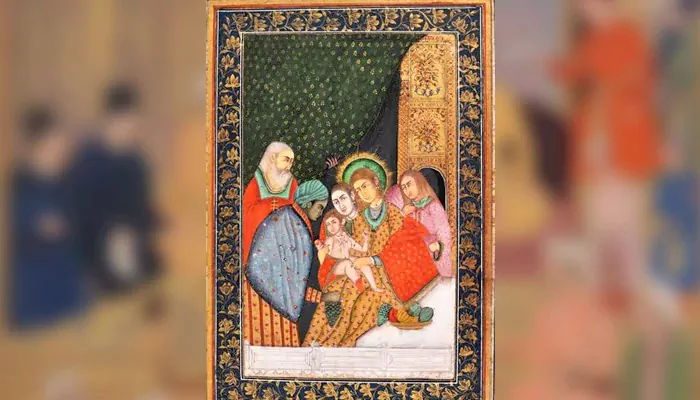

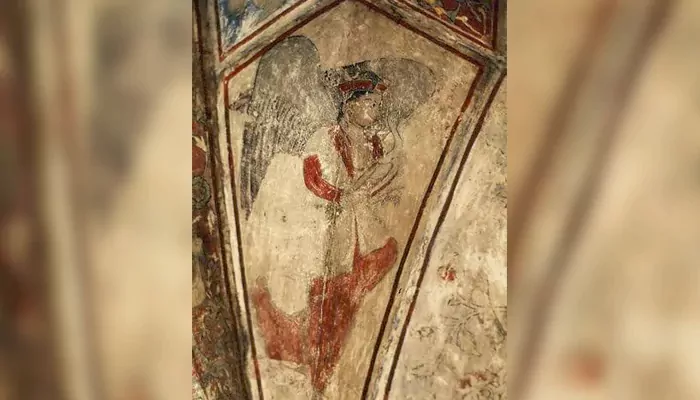

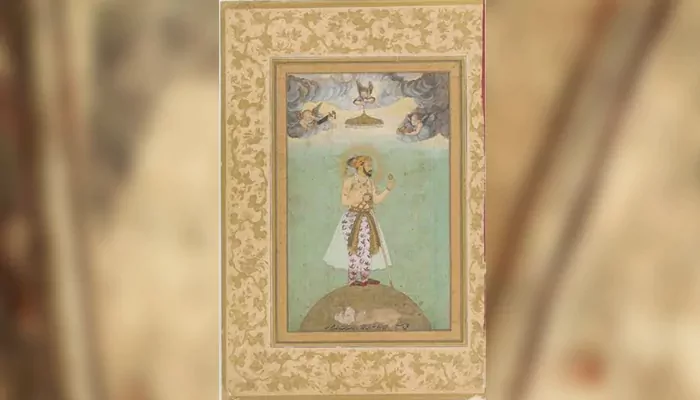

One of the earliest giveaways of this East-meets-West visual mash-up is the sudden appearance of angels. Yes, literal angels with wings and halos in Mughal miniatures. These weren’t Indian in origin. They came straight out of Christian iconography.

Akbar, Jahangir, and even Shah Jahan were fascinated by these exotic figures. They even had Mughal artists copy entire scenes from European prints. Look at the “Adoration of the Magi” and compare it with Mughal court depictions. You’ll notice similar postures, expressions, and even outfits, just with more turbans.

European priests like Father Monserrate and Father Xavier didn’t just preach. They brought copper engravings and illustrated manuscripts as gifts. The Mughals responded with curiosity rather than hostility. According to some historians, Akbar used to set up a translation bureau, and Mughal artists got a free masterclass in European realism.

Suddenly, Mughal portraits got sharper. There was depth. There were shadows. Drapery flowed more naturally. Eyes sparkled with reflection. It wasn’t just paint, it became personality.

If you spot a man with a pointy nose, soft beard, and strangely European attire in a Mughal painting, don’t worry; you haven’t imagined it. European diplomats, merchants, and priests were painted into Mughal art, sometimes even in religious scenes.

Painters like Basawan and Kesu Das absorbed Western techniques and didn’t hesitate to experiment. The result? A hybrid art form that retained Mughal finesse while adopting European naturalism.

This wasn’t just artistic appropriation. It was admiration. And it was mutual. Dutch and Portuguese collectors were so impressed that they took these miniatures back to Europe. Today, museums from London to Lisbon proudly display Indo-European art that narrates stories of power, travel, diplomacy—and artistic curiosity.

Some of these paintings even include imagined scenes like the Madonna and Child shown in Mughal-style robes or European kings in an Indian court. It was creative freedom, centuries before it became trendy.

By the time Aurangzeb took over, Mughal art leaned more toward orthodox themes. The Jesuit influence faded. But its legacy remained in the shading, in the storytelling, and in the way Indian painters began seeing the world beyond flat surfaces.

Emperor Jahangir once commissioned a painting that showed himself holding a globe, surrounded by angels, and even cherubs—straight out of a Renaissance art book!

The term “Muraqqa” (album) used for Mughal painting collections was also influenced by the European practice of compiling illustrations in books.

So next time you see a Mughal miniature painting, don’t just admire the elegance, play art detective. Look for the shadows. The cross-cultural cameos. The Western flourishes on an Eastern scroll.

These paintings are more than just royal portraits. They’re visual proof that the world was always more connected than we think.