December 27, 1911: The Day School Children Made History by Singing "Jana Gana Mana" for the First Time at INC Calcutta

- Devyani

- 1 month ago

- 4 minutes read

India’s future anthem first rang out not in Parliament or at Red Fort, but from the small, steady voices of schoolchildren in a crowded Calcutta hall.

On a winter morning in Bowbazar, Calcutta, in late December 1911, as the winter sunlight slanted across the neighbourhood and the hum of rickety tramlines filled the air, delegates gathered in a modest single-storey hall called Bharat Sabha, dressed in starched dhotis and woollen shawls. Inside, the annual session of the Indian National Congress was in full swing, wrestling with questions of empire, self‑respect, and the uneasy new fact of Delhi being declared the capital. And then, on 27 December - the second day of the session - something quieter but, in hindsight, far more enduring happened: a group of schoolchildren walked up and began to sing a new Bengali hymn written by Rabindranath Tagore.

Tagore’s hymn, a niece, and a new sound

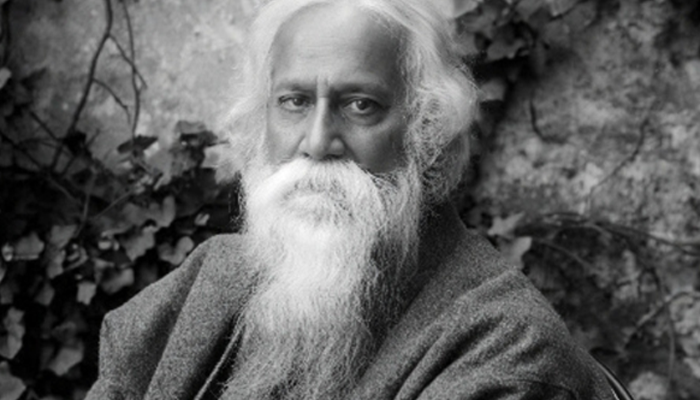

The song was the opening stanza of Bharoto Bhagyo Bidhata, a Brahmo Samaj hymn Tagore had composed earlier that month, its lyrics weaving geography and destiny, from Punjab, Sindh, Gujarat, Maratha, into one continuous plea to a guiding adhinayak, not to any emperor on horseback. Some British papers, and even a few Indian critics, tried to read it as praise for George V, fresh from the 1911 Delhi Durbar, but Tagore later wrote bluntly that he was invoking “the Dispenser of India’s destiny,” not a monarch in a plumed crown.

Kobiguru Rabindranath Tagore

Crucially, the song didn’t debut from some booming baritone; it came from Sarala Devi Chaudhurani - Tagore’s niece, a nationalist in her own right - and a group of her students, their voices carrying across the Congress hall as they sang before INC president Bishan Narayan Dhar and leaders like Ambika Charan Mazumder and Bhupendra Nath Bose. For a country still treated like a subject race, that image - a woman educator leading schoolchildren before the top brass - was quietly radical.

From Congress floor to national memory

The Tattwabodhini Daily Newspaper

After the session, the hymn appeared in Tattwabodhini Patrika under the title Bharata Vidhata, reaching Brahmo and reformist circles even if the wider public would take time to catch up. Over the next decades, it travelled in typically Indian ways: sung at Adi Brahmo Samaj gatherings, adapted into other tongues, performed by choirs long before All India Radio or Doordarshan made anything “official”. Only in January 1950, that is almost forty years after those children sang in Bowbazar, did the Constituent Assembly adopt the first stanza, retitled “Jana Gana Mana”, as the national anthem, with Dr Rajendra Prasad announcing it as an expression of the new republic’s sovereignty. By then, that Calcutta morning had hardened into legend, even if most schoolbooks mention the date and skip the schoolchildren.

Hear the National Anthem in the voice of its creator, Rabindranath Tagore.

(@cmc_indore/Instagram)

Why that school assembly still matters

In a way, the 1911 performance feels oddly contemporary. A song born in a local language, premiered in a cramped city hall, carried by young voices and a woman who believed classrooms could be political spaces - that’s not far from how today’s protest music or campus anthems catch fire.

And there’s a small irony Kolkata folks quietly cherish: long before “national integration” became a slogan and before debates erupted over who the anthem was really praising:

It was this city - its Brahmo networks, its reformist salons, its slightly chaotic Congress sessions - that gave India the first, trembling rendition of the tune we now stumble through at morning assembly, cinema halls, and cricket matches.