How the Quit India Movement lit the fire of final resistance against the British Raj

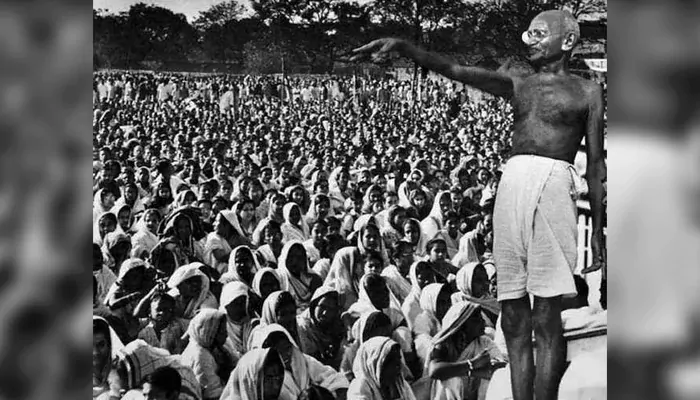

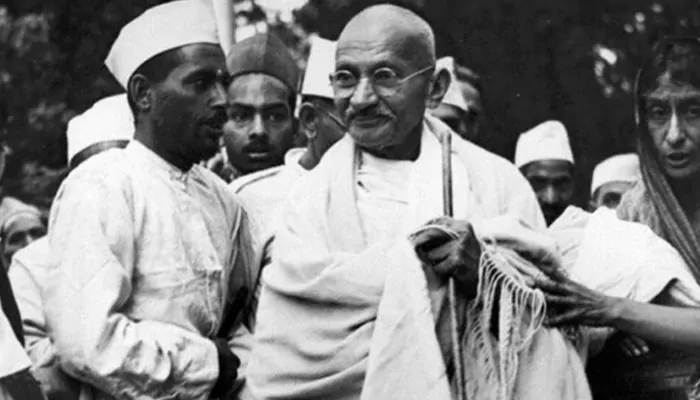

It was the sweltering evening of August 8, 1942. Bombay's Gowalia Tank Maidan buzzed with an anxious crowd. The air was thick with tension and anticipation. Then, Mahatma Gandhi stepped up to the podium. His voice, though frail with age, rang with unshakable resolve: "The mantra is Do or Die. We shall either free India or die in the attempt." Those words didn't just stir hearts—they detonated a nationwide uprising.

What followed wasn't just a protest. It was a people's call to arms—not of weapons, but of will.

When war abroad became war at home

World War II raged across Europe and Asia, but the tremors were felt in the heart of colonial India. Without so much as a polite nod to Indian leaders, Britain dragged India into the war in 1939. The Defence of India Act was revived, martial law tightened its grip, and Indian soldiers—2.5 million of them—were roped in, mostly without choice.

For Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, this was the final straw. Britain's wartime needs had once again overridden Indian voices. Worse still, the threat of Japanese invasion loomed, and the British, who were using Indian soil as a military base, seemed unwilling to let go of their imperial hold.

(Credit: Civils Daily )

A post-dated cheque from a failing bank

The British, sensing restlessness, sent Sir Stafford Cripps to offer a compromise in 1942—help us in the war now, and we'll talk about self-governance later. Gandhi scoffed at the proposal, famously likening it to "a post-dated cheque on a failing bank."

The Congress wasn't buying vague promises. On July 14, the party passed the Quit India Resolution, giving Gandhi full authority to launch a civil disobedience campaign. The die was cast.

A nation rises as its leaders fall

Just hours after Gandhi's historic "Do or Die" speech, the British struck back. Overnight, nearly all senior Congress leaders, including Nehru and Patel, were arrested. Gandhi himself was confined in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune.

The colonial government had hoped that by cutting off the movement's head, the body would fall. But the opposite happened.

Without their leaders, young Indians stepped up. Underground radio broadcasts, secret newspapers, and spontaneous uprisings ignited like wildfire. Protests spread from Maharashtra to Bengal. Strikes, student walkouts, and sabotage of British infrastructure became the new normal.

When non-violence met the iron fist

The British response was ruthless. Entire regions were placed under martial control. Trains and telegraph lines were bombed, curfews were enforced, and in some areas, aircraft even fired on crowds. At least 1,000 Indians lost their lives, and more than 60,000 were arrested in the months.

Yet, the spirit of resistance refused to die. The movement's heartbeat continued to echo through villages and towns—even as the leadership languished in prison.

A movement that didn't “fail"

Critics often label the Quit India Movement as a tactical failure—it didn't force the British to quit immediately. But its more profound impact was undeniable. For the first time, it became clear that India could no longer be governed without Indian consent.

It was also a turning point for the British themselves. War-weary and facing mounting global pressure, especially from the United States, they realised the Raj's days were numbered. The seeds of decolonisation were now sown.

Ripples that led to partition

While the Congress sat behind bars, the Muslim League surged. Mohammed Ali Jinnah, who opposed the Quit India resolution, worked with the British and expanded his base dramatically. By the war's end, the League's clout had grown tenfold—laying the foundation for Pakistan.

Thus, while Gandhi's “Do or Die" cry unified many, it also marked the beginning of parallel political destinies—of a free India and a divided subcontinent.