Why Hyderabad Had to Be Part of India: Understanding the Logic Behind Operation Polo

- Sayan Paul

- 6 months ago

- 7 minutes read

Hyderabad's integration became a decisive step in shaping the Indian nation.

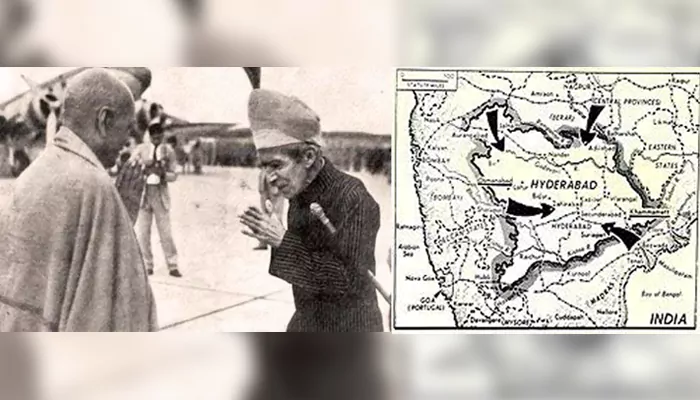

When India gained independence in 1947, it wasn’t the neat and clean break we often imagine. As the British left, they also left behind a big question: what happens to the 500-odd princely states? Each was given a choice to join either India or Pakistan or stay independent. For Prime Minister Nehru and Home Minister Sardar Patel, the goal was about building one unified nation. While most states agreed, Hyderabad refused. The Nizam of Hyderabad wanted to remain independent. Now, it might’ve sounded like a personal choice on paper, but for India, it was a ticking time bomb. So, in 1948, India launched a military action named Operation Polo to bring Hyderabad into the Union.

However, what made Hyderabad so important? Why was letting it go simply not an option? In this article, let’s dig into the logic behind that crucial decision and understand why India went to such lengths to make sure Hyderabad became a part of the country.

Hyderabad: A Kingdom Within

To understand the gravity of the problem, one has to grasp the scale and singularity of Hyderabad State in 1947. Sprawling across 82,000 square miles (about the size of present-day Karnataka), it encompassed a population of roughly 16 million, over four-fifths of whom were Hindu. Yet power rested firmly with a Muslim elite, led by the 7th Nizam, Osman Ali Khan, reputed to be the world’s richest man (according to some estimates) at the time. His court shimmered with diamonds and etiquette, and the state functioned like a parallel nation, which had its own currency, railways, and even an airline.

But for all its glamour, Hyderabad was a geopolitical anomaly, landlocked deep inside Indian territory, with no access to the sea and no physical border with Pakistan.

Still, the Nizam held out. He imagined Hyderabad as an independent dominion, perhaps under the symbolic umbrella of the British Commonwealth. He refused to accede to either India or Pakistan, hoping international diplomacy would protect his realm.

But for the Indian leadership, this vision was untenable. In his authoritative India After Gandhi, Ramachandra Guha calls Hyderabad “a test case”, a crucible for the integrity of a nation barely held together after the trauma of Partition.

Patel, Nehru, and the Mission to Integrate

The task of welding princely India into a republic fell, in large part, to Sardar Patel, the Home Minister with the temperament of a statesman and the instincts of a realist. Patel had already persuaded or compelled most of the princely states to join the Union. But Hyderabad (along with Junagadh and Kashmir) remained recalcitrant.

Patel believed firmly that Hyderabad’s defiance was not only a regional quirk but a national threat. "A cancer in the belly of India," he called it directly. Nehru, more idealistic and cautious, preferred a diplomatic approach, but he too understood the stakes. India had just been ripped apart along religious lines. A fragmented map dotted with independent kingdoms (especially one as central and symbolically potent as Hyderabad) would fatally compromise the dream of a secular, united republic.

If India gave in here, the entire fabric of the Union might begin to fray.

Why Independence for Hyderabad Was Inconceivable

What made Hyderabad’s independence not just undesirable, but intolerable? The reasons ran deep across geography, security, demography, and economics.

A Central Thorn

Hyderabad sat right in the middle of the Indian subcontinent, its borders touching present-day Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana. If it remained independent, it would form a hole in the map and a landlocked wedge that disrupted territorial continuity and crippled administrative coherence.

As V.P. Menon, Patel’s trusted advisor and the author of The Story of the Integration of the Indian States, wrote with characteristic clarity: “An independent Hyderabad would have been a dagger pointed at India’s heart.”

The Razakar Menace

The Nizam’s refusal to join India might have been dismissed as aristocratic stubbornness - were it not for the rise of the Razakars. This paramilitary group, led by the hardline cleric Kasim Razvi, was formed to resist integration. Under Razvi, the Razakars unleashed a campaign of terror, targeting dissenters, looting villages, and violently suppressing the Hindu majority. Their actions pushed Hyderabad to the brink of civil war.

Delhi watched with growing alarm. What had begun as a constitutional dispute was becoming a security emergency.

Communal Fragility

India in 1947-48 was a nation nursing fresh wounds from Partition. The last thing it could afford was a communal flashpoint at its core. With Hyderabad’s demographic mismatch (Hindu subjects ruled by a Muslim monarch) and the Razakars’ violence, fears of sectarian conflict loomed large. The risk wasn’t theoretical. A protracted insurgency in Hyderabad could easily spill over into neighboring states.

Economic Concerns

Hyderabad wasn’t just culturally rich; it was economically crucial as well. Its fertile land and thriving markets were deeply entwined with the surrounding regions. An independent Hyderabad could disrupt transport links, trade flows, and agricultural systems at a time when India was already scrambling to stabilize post-colonial food supplies and infrastructure.

The Domino Risk

Perhaps the most dangerous consequence of tolerating Hyderabad’s independence was the precedent it would set. If the Nizam could wrangle sovereign status, what would stop Bhopal, Travancore, or other princely enclaves from making similar demands?

Diplomacy Breaks Down

For over a year after independence, Patel and Nehru tried to solve the Hyderabad impasse through negotiation. Delhi offered generous terms: Hyderabad could retain significant internal autonomy in exchange for accession. But the Nizam hesitated. He reached out to the United Nations, flirted with British sympathy, and even explored a sea route via Portuguese-held Goa.

None of it bore fruit, though. Meanwhile, the Razakars intensified their campaign. Reports came in of attacks on Indian border patrols, stockpiling of arms, and growing anarchy inside Hyderabad.

Delhi's patience was over. On September 7, 1948, the Indian government issued an ultimatum: accede, or face intervention. But the Nizam stood firm. And hence, Operation Polo was now inevitable.

The Lightning Strike of Operation Polo

At dawn on September 13, 1948, Indian troops crossed into Hyderabad. Codenamed "Operation Polo" (a nod to the Nizam’s love for the sport), the mission was decisive. Commanded by Major General J.N. Chaudhuri, the Indian Army faced minimal resistance. The Razakars, poorly trained and disorganized, crumbled in the face of a professional military force. In just five days, Indian forces entered Hyderabad city. The Nizam surrendered on September 17.

This is one of the most important videos in Indian History - the formal surrender of Hyderabad Army in Operation Polo. How many even know it exists or watched it? In absence of Nizam's speech, this is the only one we have which orders capitulation. pic.twitter.com/PnnzFsTOKp

— Eztainutlacatl (@cbkwgl) June 16, 2025

(Credit: Eztainutlacatl)

The operation had ended. But the reckoning had just begun.

What Followed

In the aftermath, India had secured its geographic integrity, but at a human cost. Though the official military campaign was brief, communal reprisals swept parts of the state in its wake. Thousands, particularly Muslims, lost their lives in retaliatory violence - estimates vary widely, from 10,000 to as many as 40,000. A 2013 report by the erstwhile Andhra Pradesh State Minorities Commission acknowledged the scale of these atrocities. For many, Operation Polo remains a complicated memory, particularly an act of national necessity, shadowed by local trauma.

The Nizam was allowed to keep his title and wealth, and in time, even served as the ceremonial Governor of Hyderabad. The state itself was integrated into the Indian Union and later reorganized, eventually giving rise to modern Telangana.

Gen. J. N. Chaudhuri – the man who led Indian troops into Hyderabad in 1948 during Operation Polo, ensuring its integration into India.

— Hotṛ (@Rathatreya_) July 22, 2025

Later, as Army Chief (1962–66), he rebuilt a demoralized force after the China war.

Warrior. Reformer. Strategist. pic.twitter.com/wmmezt751K

(Credit: Hotṛ)

Operation Polo sealed Patel’s legacy as the man who held India together with a steely grip. But it also left behind unanswered questions about the costs of unification.

Letting Hyderabad remain independent would have fractured the core of India as a nation, making it a fragile attempt to build unity out of multiplicity. As Patel once said, with characteristic bluntness: “We are building a nation, not a mosaic of rival principalities.”