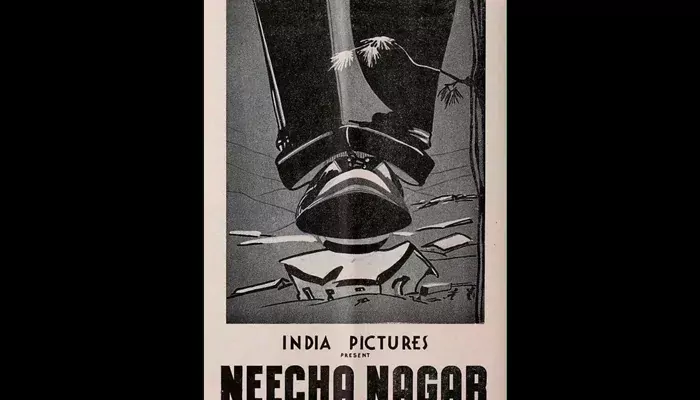

A landmark in Indian cinema, ‘Neecha Nagar’ boldly exposed social injustice—earning global recognition while facing silence at home

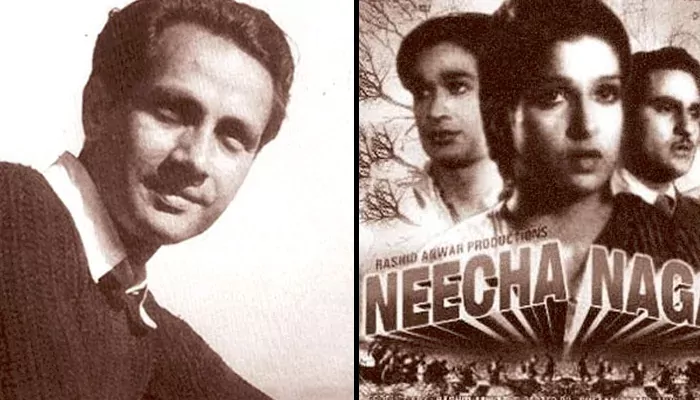

In 1946, just a year before India’s independence, a quiet revolution took place—not on the streets, but on celluloid. Neecha Nagar, directed by a young and untested Chetan Anand, broke away from Bollywood norms. It had no songs, no stars, and no happy endings. Yet it dared to speak truth to power. It became the first—and still the only—Indian film to win the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

But here’s the twist: while the world applauded it, India looked away.

The story of Neecha Nagar wasn’t imagined in a vacuum. It was adapted from Maxim Gorky’s The Lower Depths, but it was transformed into a piercing critique of Indian society under colonial rule. The film portrayed two classes—one that lived in luxury on the hill (Ooncha Nagar), and the other that suffered in the valley below (Neecha Nagar). The powerful polluted the water source of the poor, leading to illness and death. And when the people resisted, they were met with apathy and exploitation.

Through this allegory, Anand and writer Khwaja Ahmad Abbas turned a spotlight on colonial indifference and class cruelty. It wasn’t just a story. It was a protest.

The team behind Neecha Nagar was young, fearless, and new to the cinema industry. Chetan Anand had no previous experience as a director. The film marked the debut of Ravi Shankar as a music composer. It starred unknown faces, such as Kamini Kaushal and Rafiq Anwar, and was shot on a shoestring budget.

There were no crowd-pleasing numbers. No glamour. Just stark realism. The filmmakers leaned heavily on expressionist visuals—low lighting, shadows, and framing that made the class divide feel suffocatingly real.

In 1946, Neecha Nagar was sent to the first Cannes Film Festival in France. Against all odds, it won the festival’s highest honour—the Grand Prix, which would later be renamed the Palme d’Or. It shared the top spot with films by international legends like David Lean and Roberto Rossellini.

For a debut Indian film to compete—and win—on a stage dominated by global giants was unprecedented. It was the first time India had announced itself to world cinema with such confidence.

And yet, despite this international triumph, Neecha Nagar never reached theatres across India in any meaningful way. Distributors were nervous. The film’s bold stance against inequality and authority—seen as a criticism of both colonial rulers and local elites—made it too “political.” They wanted songs. They wanted romance. They wanted market safety. Anand refused to compromise.

The film was barely released. It remained more of a rumour than a reality to Indian audiences.

For years, the only existing print of Neecha Nagar was feared lost. Then, in the 1960s, a damaged copy surfaced in a Kolkata scrapyard. Thanks to film archivists, it was salvaged and preserved. But by then, the film had become more of a legend—a whisper of what could’ve been a movement.

Despite its near-disappearance, it planted seeds. Satyajit Ray later acknowledged it as an inspiration. Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak, too, took cues from its unflinching realism.

More than seven decades later, Neecha Nagar stands as a rare blend of cinema and conscience. Its themes—displacement, environmental injustice, class exploitation—still resonate. In a country where films often shy away from uncomfortable truths, Neecha Nagar chose to confront them. It chose honesty.

It may not have filled theatres. But it filled a gap in our cultural memory—a film that didn’t just entertain, but challenged.

Neecha Nagar didn’t change the box office. But it changed the language of Indian cinema. Before parallel cinema had a name, it had a heartbeat—and it beat in the narrow lanes of Neecha Nagar. As India continues to wrestle with the same inequalities, the film feels more timely than ever.

It remains a reminder: that art, when brave enough, can speak even when no one listens.