When Gandhi Stood Up for Bihar’s Farmers: The Untold Story of Champaran

- Sayan Guha

- 5 months ago

- 3 minutes read

How Gandhi’s first satyagraha in India changed the lives of Champaran farmers

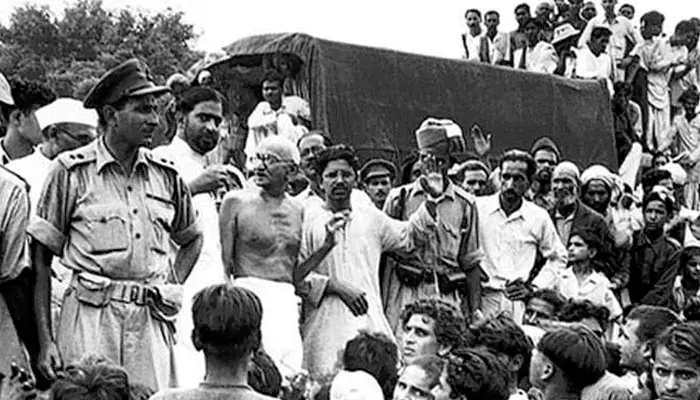

April 17, 1917. The dusty fields of Champaran in Bihar buzzed with anxious whispers. A lone figure arrived—not with armies or weapons, but with quiet resolve and a notebook. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi had come, summoned by the desperate pleas of Rajkumar Shukla, a tenant farmer whose community had long suffered under the cruel grip of indigo planters. Little did the villagers know that this day would mark the dawn of India’s first major experiment in civil disobedience.

The weight of the Tinkathia chains

At the core of Champaran's suffering was the Tinkathia system, a brutal rule that forced peasants to grow indigo on a portion of their land, regardless of soil richness or personal need.

European markets had long shifted away from natural indigo for synthetic dyes, yet planters persisted with the system, pushing farmers into debt while increasing their own profits. Fields became worn out, food grew scarce, and hope faded just as quickly. The soil itself seemed to resist the burden of exploitation.

Listening before leading

Gandhi did not march in with fiery speeches or grand declarations. Instead, he sat beneath banyan trees with farmers, pen in hand, recording over 8,000 testimonies of suffering. He understood that illiteracy was as much a tool of oppression as the planter’s whip.

Schools appeared in villages such as Barharwa Lakhansen, Bhitiharwa, and Madhuban, offering lessons in basic literacy, hygiene, and practical skills. Kasturba Gandhi, his steadfast companion, became a symbol of empowerment, teaching local women and creating spaces for voices that had long been silenced.

(Credit: INC )

A movement built on empathy

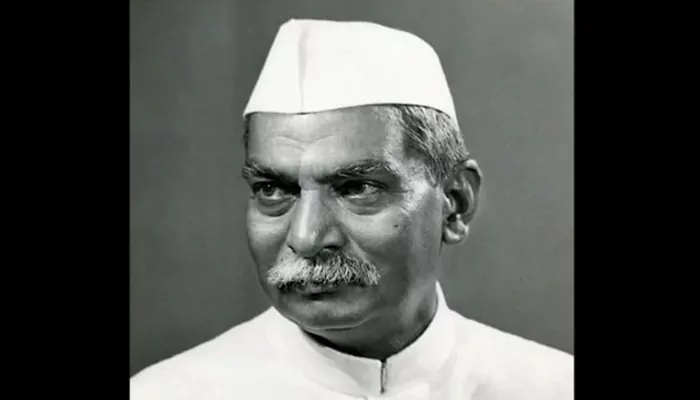

Joined by young leaders like Rajendra Prasad, JB Kripalani, and Brajkishore Prasad, Gandhi cultivated a network of volunteers who educated, documented, and rallied the oppressed. Women, previously excluded from political action, emerged as influential narrators of resilience, sharing their experiences and inspiring collective courage.

The psychological impact was profound. When British officials demanded that Gandhi leave, he calmly refused, asserting moral authority over imperial decree. For the first time, the farmers saw someone refuse to bow before the empire on their behalf. Fear turned into self-belief.

(Credit: Wikipedia )

Justice, not vengeance

Gandhi’s insistence on dialogue led to the formation of a government commission to investigate grievances. His presence ensured that the farmers’ voices were heard. The Tinkathia system was abolished, and illegal dues were partially refunded; the Champaran Agrarian Act of 1917 became a landmark in colonial legal reform.

Beyond policy, Champaran transformed consciousness. Gandhi wove agrarian justice, education, women’s participation, and environmental stewardship into a blueprint for moral resistance. The fields of Bihar were not merely liberated—they became classrooms, incubators of civic awareness, and stages for the assertion of human dignity.

(Credit: Adda247)

Legacy etched in soil and spirit

Champaran was more than a protest — it was the first stroke on a nation's moral canvas, a testament to non-violence and the power of truth. Renowned figures from Rabindranath Tagore to J.L. Nehru recognised its importance. For Dr Rajendra Prasad, it was a training ground in servant leadership. For India, it was a movement that shifted nationalism from elite discourse to the actions of the people.

Today, the memory of Champaran reminds us that courage can flourish in quiet defiance, that empathy can overthrow tyranny, and that the seeds of change often grow where moral conviction meets collective will.