Here's a speculative journey into how Indian history and identity might have evolved if Shivaji’s Maratha Empire had spread across the entire subcontinent.

Shivaji (during the 17th century) envisioned a Maratha empire that stretched across the entire Indian subcontinent, free from Mughal dominance, ruled by its own people, and rooted in the idea of swarajya or self-rule. While he didn’t live long enough to see that dream fully realized, he came incredibly close. Through sharp military strategy and a strong administrative vision, he built the foundation of what could have become a pan-India Maratha empire. His legacy lived on through his successors, who pushed the Maratha influence further than anyone expected.

Now here comes a question. What if Shivaji had actually succeeded in his lifetime? What if his dream of a united, Maratha-ruled India had come true? Would it have changed the course of Indian history? Would colonial rule have taken a different shape or not arrived at all? In this article, we take a journey into the India that could have been, with a blend of imagination and research that reimagines history.

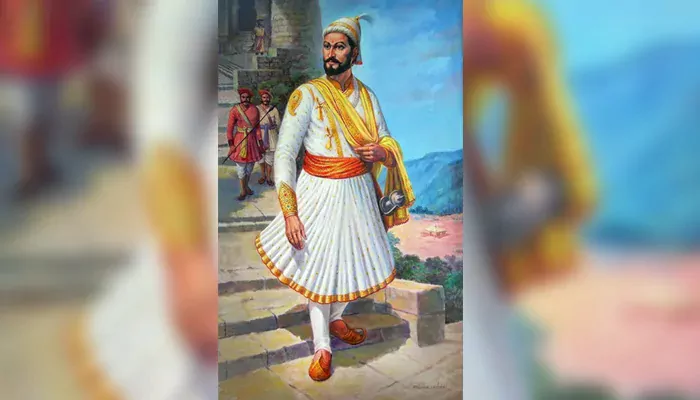

To imagine the alternative, we must first understand the original. Shivaji was born in 1630 into a Maratha noble family serving the Bijapur Sultanate. But he quickly charted his own course. While still in his teens, he began seizing hill forts and testing the patience of the Deccan powers. The famed encounter with Afzal Khan in 1659 (where Shivaji emerged alive and victorious) was a public assertion of his rising authority, more than just a military triumph.

When he crowned himself Chhatrapati in 1674, it marked the formal birth of Swarajya, a kingdom governed not by imperial decree but by indigenous principles. His administration was meticulous with an Ashtapradhan council to handle civil and military affairs, land revenue reforms that sought fairness for cultivators, and a coastal navy that checked European merchants and safeguarded Konkan trade. Over 300 forts, each positioned with tactical precision, served as nodes of control and resilience. As historian Jadunath Sarkar observed, Shivaji’s brilliance lay in “organizing a national war of liberation… with the soul of a statesman and the heart of a patriot.” Still, the Maratha state remained largely regional at the time of his death. His premature passing left the empire in the hands of successors who expanded it, but never fully realized his vision. What if he had been the one to do it?

Let us now step into that alternate reality. Suppose Shivaji, armed with alliances and momentum, lives into the 1690s. He capitalizes on the aging Aurangzeb’s overextended campaigns, and Maratha forces push decisively north. By 1690, Delhi falls. The Mughal Empire collapses abruptly.

The contours of such an empire would be markedly different from the centralized Mughal order. Shivaji’s style was federal and adaptive. Instead of imposing uniformity, he integrated local power centers through negotiation and shared interest. Historian Stewart Gordon, in The Marathas 1600–1818, noted that Shivaji “excelled at drawing fractured loyalties into coherent frameworks.” The Ashtapradhan model might have evolved into provincial councils, with loyal sardars and local elites forming the backbone of governance. Pune or Raigad, not Delhi, may have remained the symbolic capital. And unlike the Persianate aesthetic of the Mughals, the culture of the empire would reflect a Marathi-Hindu ethos tempered by pluralism. Shivaji never imposed religious uniformity; he was guided more by pragmatism than dogma.

The British East India Company’s rise hinged on opportunism: exploiting the Mughal decline, playing Indian rulers against one another, and gradually expanding from trade to control. But a consolidated, militarily alert Maratha empire would have presented a far less penetrable target.

Even during his lifetime, Shivaji understood the threat of European sea powers. His fortresses at Sindhudurg and Vijaydurg were constructed with naval resistance in mind. In this alternate history, a fortified western coast (patrolled by a disciplined navy) could have pushed back against British ambitions. The French, Dutch, or even the Ottomans might have become preferred trade partners, diluting British influence before it took root.

In such a timeline, there is no Plassey in 1757, and no Buxar in 1764. The British remain coastal traders, not imperial overlords. India’s economic output (the envy of Europe in the 17th century) stays within Indian hands. And the industrial wealth of Britain, which in reality was fueled in part by the exploitation of India, takes a different shape or perhaps never reaches the same height at all.

Shivaji’s legacy in matters of religion has long been debated, but most scholars agree that he was remarkably tolerant for his time. He employed Muslims in high offices, protected Islamic institutions, and revered saints of all faiths. So, a pan-Indian Maratha rule might have extended this ethos further. The divisive jizya tax (reimposed by Aurangzeb) would have no place. Religious identity would matter less than political loyalty. The Bhakti movement, with its emphasis on personal devotion and social reform, could have spread more freely, overlapping with Sufi traditions and creating a more cohesive spiritual landscape.

British divide-and-rule policies, which later weaponized religious and caste identities, might never find fertile ground in this more organically pluralistic setting.

A successful Maratha unification in the early modern period could have rewritten the story of Indian nationhood. The idea of India as a single, sovereign entity might have taken root two centuries before it did in our timeline. And it would be a very different India.

Marathi could have emerged as the administrative language, though not at the expense of others. Given Shivaji’s sensitivity to local identity and regional tongues, Tamil, Bengali, Kannada, and Gujarati would likely flourish under a policy of multilingual governance.

Socially, too, the effects would be deep. Shivaji's record of meritocratic appointments and his disdain for hereditary privilege suggest that caste and class structures could have been more fluid. Feudal excesses like bonded labor were curtailed during his reign. If that trend had continued at scale, it might have reshaped hierarchies across India.

Geopolitically, this India could rival the Ottoman Empire. Economically independent, culturally confident, and militarily secure, it might have led a non-Western model of development that later nations would seek to emulate rather than conquer.

We remember Shivaji today as a regional hero, or more precisely a defiant thorn in the side of empires. But in this reimagined history, he becomes the architect of a unified Indian state long before modern nationalism emerged.

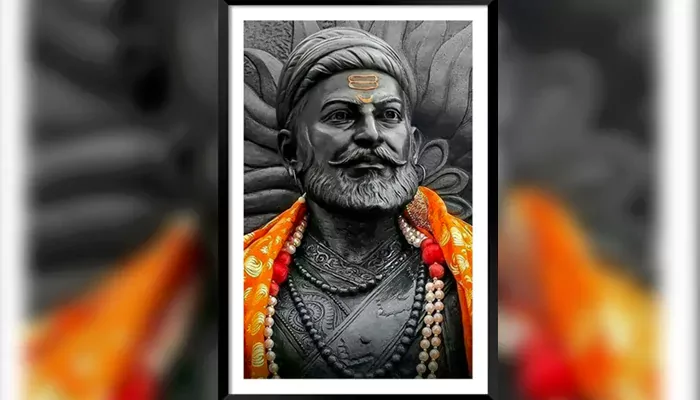

Statues of Shivaji already rise high across Maharashtra. In this alternate timeline, they would stand across every province, from Bengal to Punjab, Tamil Nadu to Kashmir. His legacy would not be invoked in passing speeches but embedded in the very architecture of Indian governance. And the world would speak of the “Indian century” as a fact of the past. The idea of Swarajya, once a regional slogan, would be the founding principle of an empire that stood tall, and preserved its soul.

In the end, history did not grant Shivaji the years he needed. But the question remains: what if it had? And in imagining that answer, we catch a glimpse of a different India that's centuries ahead of its time.