Had Rani Lakshmibai won the Battle of Jhansi, India’s colonial fate might’ve taken a drastically different turn.

Rani Lakshmibai’s fight against the British to free Jhansi is now part of legend. We have read about it in books, seen it play out in films, and grown up admiring her courage. In every version, she is a hero who may have fallen in the end, but never actually lost. Still, have you ever paused to wonder: What if that ending was different? What if Lakshmibai had won the Battle of Jhansi? What would’ve happened next? Would the rebellion of 1857 have turned into something much bigger? Could her victory have changed the way India’s freedom struggle unfolded?

In this story, let’s turn the pages of an alternate history, where the Rani wins, and in doing so, maybe changes India’s fate forever. Please keep in mind that what follows is a blend of imagination and historical insight, drawing from both creative speculation and research-based facts.

By early 1958, Lakshmibai’s position was precarious. She had fortified Jhansi, but British troops under Sir Hugh Rose had surrounded it. They brought artillery, discipline, and a cold sense of purpose, while she had loyalty and a city to protect.

The odds were not really with her. Reinforcements promised by Tantia Tope arrived too late. Her defenders, although spirited, were outgunned, and the bombardment battered the city’s defenses. Hence, when the breach came, it was genuinely brutal.

She escaped under the cover of night, fleeing toward Kalpi and then Gwalior, where she would make her final stand. The Company, determined to make an example, called it a “necessary suppression.” But across India, the story carried a different weight. It was about a queen who refused to surrender, even when surrender seemed inevitable.

But let’s step into another version of the story. Suppose Sir Hugh Rose never breached the fort. Suppose the final charge failed. His forces are forced to pull back. And Jhansi holds.

Such a turn would have been more than a tactical shift. Jhansi’s geography placed it at the heart of rebel activity in Central India. A secured stronghold there could have served as a rallying point not just for morale, but for coordination. The rebellion, often described as fragmented, might have started to find form.

Other leaders (Nana Saheb, Tantia Tope, and even the embattled sepoys in Awadh) would likely have taken note. Not every flame would have reignited, but some might have.

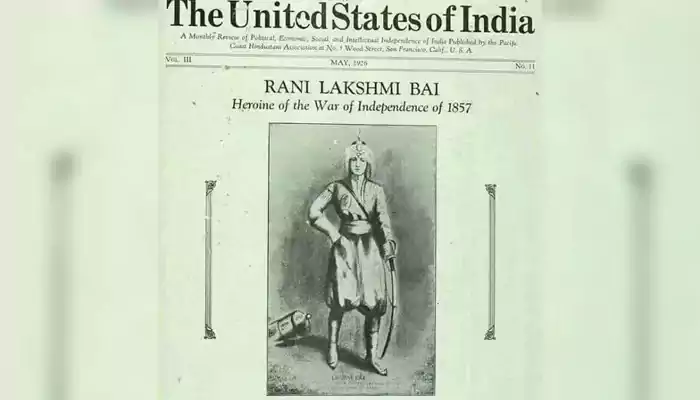

The iconic warrior queen Rani Lakshmibai was born on Nov 19, 1828 pic.twitter.com/pjyHxVOaKD

— Newsflicks (@newsflicks) November 19, 2016

(Credit: Newsflicks)

It wouldn't have reversed every British gain. Delhi had already been lost. But with Jhansi unbroken, the rebellion could have found new momentum and a clearer direction.

The revolt of 1857 lacked central leadership, as there was no unified command and no coherent vision. But Lakshmibai had the kind of presence that could’ve changed that. She didn’t need to crown herself empress. Her authority would’ve rested in action, in leading from the front, and in showing that British defeat was not a fantasy.

A provisional rebel center in Jhansi wasn’t out of the question. And once one node of resistance proved it could endure, others might have begun to coordinate (if not militarily, then politically).

Would this have led to independence? Probably not right away. But it could surely have prompted the British to rethink their next move. After all, this was an empire still reeling from the Crimean War. With public fatigue mounting at home and stretched resources abroad, a drawn-out campaign across India was not ideal. They might have chosen negotiation over annihilation. Perhaps a model of indirect rule, allowing local autonomy under a British umbrella (akin to what Canada or Australia would later receive).

And if that had happened, the hard pivot to direct Crown rule after 1858 might never have come. India’s princely states might have retained more sovereignty. The bureaucratic overreach and extractive taxation policies of the later Raj might never have taken such deep root. Even Partition, born decades later from wounds the Raj helped deepen, might have been averted in a different political climate.

There’s another story hidden inside the what-if: about power, and who’s allowed to wield it.

If Lakshmibai had not only survived but also ruled a victorious Jhansi, she wouldn’t have remained an icon of martyrdom. She’d have become a living model of female sovereignty. In 19th-century India, that alone would’ve been radical... and not just in symbolism. A ruling queen with battlefield experience, administrative authority, and mass legitimacy could have shifted perceptions of gender roles long before the rise of 20th-century feminism.

We might have seen more women stepping into visible leadership in regional uprisings. Reform movements (especially those addressing women's education, child marriage, and widowhood) could have found earlier traction.

Feminist historians like Geraldine Forbes have traced how early nationalist women drew inspiration from Lakshmibai’s story. Now imagine if she’d been a precedent.

The 1857 uprising wasn’t confined to being a local rebellion. It was watched by colonized peoples across the world. And without an iota of doubt, a victorious Jhansi might have turned Lakshmibai into a symbol far beyond India. The Times of London, in a telling moment of both sexism and respect, called her “the only man among the rebels.” One can only imagine how they might’ve responded to her victory.

In the decades that followed, anti-colonial thinkers from Turkey to Japan studied the events of 1857. As Pankaj Mishra notes in From the Ruins of Empire, Indian resistance helped shape the intellectual currents of Asian modernity. A successful stand at Jhansi could have accelerated that influence. The model of resistance might have shifted from isolated uprisings to sustained movements.

Even within Britain, the aura of invincibility around the empire might have cracked. And that matters. Once an empire starts negotiating from fear rather than confidence, its decline begins inevitably.

In this alternate timeline, Lakshmibai wouldn’t be the face on a postage stamp or a statue in a park. She’d be a foundational figure in Indian statehood.

Imagine if Indian schoolchildren recited her proclamations instead of merely memorizing dates of her death. Imagine if the Constitution bore traces of her governance principles. If the Indian political identity had formed not through lawyers and petitions, but through the lived leadership of a queen who fought, won, and ruled.

India’s national calendar might look different, too. The 15th of August would likely remain an ordinary monsoon day. Instead, 20th June 1858 (the day Lakshmibai stood unbeaten on the walls of her fort) might have marked the nation’s first taste of freedom.

Lakshmibai did not live to see the world change. But she came close to forcing it. And in asking what might have happened had her sword cut deeper into the empire, we’re not indulging fantasy. We’re tracing the edge of possibility and reminding ourselves how close history often comes to turning the other way.