The bold urdu weekly that turned British power into a punchline and made resistance a reading habit

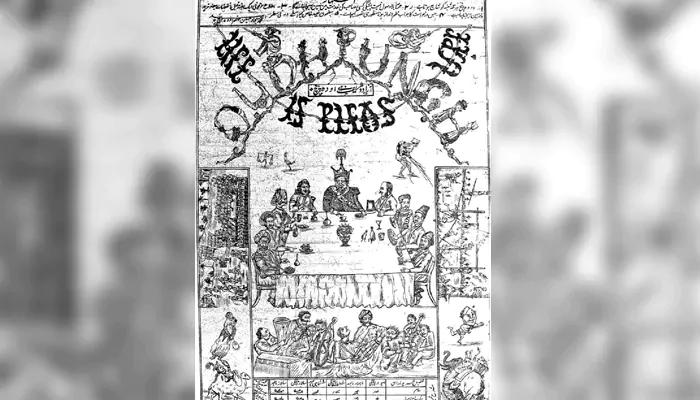

In 1877, at the height of British pomp in India, a clever magazine emerged from the heart of Lucknow. It was called Awadh Punch, often affectionately known as Hind Punch. What began as a parody of the British satirical magazine Punch quickly became something far more subversive. This Urdu weekly wielded humour like a sword, cutting through the pretensions of empire and exposing its absurdities. Its weapon of choice wasn't the rifle or the rally—it was the joke, the cartoon, the clever line that said what others dared not.

At the helm of Awadh Punch was Munshi Sajjad Husain, a bold editor with a keen sense of satire and a sharp tongue. He was no ordinary publisher. Sajjad Husain saw the power of language to provoke thought and stir dissent. In a time when the British monitored every voice, he dared to speak in one that laughed.

Under his watch, the magazine dissected British bureaucracy, mocked colonial policies, and roasted brown loyalists who tried to mimic their colonial masters. His satire was razor-edged but never vulgar. The pages were filled with irony, puns, parodies, and political cartoons that gave the British more headaches than some revolts.

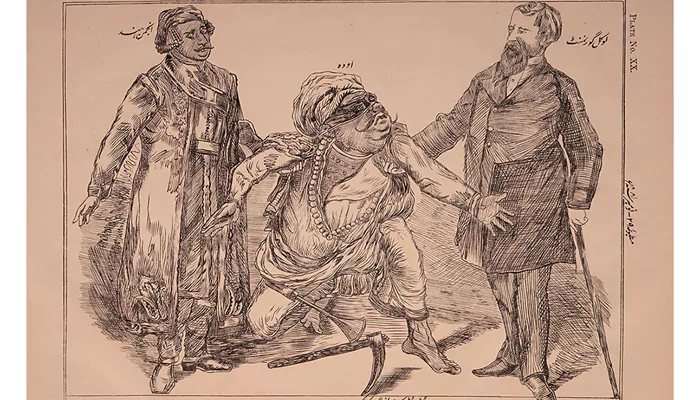

Though modelled after the British Punch, Awadh Punch was anything but colonial in spirit. Where the English original served the empire with humour, its Urdu counterpart flipped the script. It mimicked the colonial style only to expose its flaws. In cartoon panels and verses, British officers were depicted as bumbling caricatures, while Indian collaborators were portrayed as puppets wearing red coats.

The magazine spoke to an educated but restless middle class. Its jokes were not just about laughter—they were about resistance. Even complex issues, such as the Ilbert Bill controversy, which debated whether Indian judges could try British offenders, found their way into its satire. And Awadh Punch did not hesitate to take a side—it stood for equality and justice.

The soul of Awadh Punch lay in its contributors. Some of the finest minds in Urdu literature, including the sharp-tongued Akbar Allahabadi, wrote for it. Their humour had a purpose. Through poetry and prose, they ridiculed the colonial order and questioned the blind imitation of Western values.

One recurring target was the class of Indians who spoke English with pride but had little understanding of their own culture. The magazine poked fun at these 'brown sahibs', critiquing cultural mimicry and calling for introspection. Satire, in their hands, became a call for reform.

The success of Awadh Punch sparked a trend. Across India, other regional 'Punches' began to emerge—such as the Parsee Punch in Bombay, the Punjabi Punch, the Hindi Punch, and others. Some took inspiration in style; others followed in spirit. While not all were anti-colonial, many used satire to comment on society, caste, education, and politics.

By 1900, dozens of satirical magazines had been published in Indian languages. Each was a minor revolt printed on cheap paper. And together, they proved that humour, too, was a language of resistance.

The British, unsurprisingly, weren't amused. Awadh Punch often faced official disapproval and censorship. Its readership wasn't large—perhaps a few hundred—but its reach was deep, especially in academic and urban circles. By 1912, under pressure, the magazine was forced to shut down. It made a brief return in 1916, only to close permanently in 1937.

But its spirit lived on. The legacy of Awadh Punch wasn't just in its jokes—it was in the courage to laugh when others whispered. It proved that the pen could jab, and laughter could sting.

Today, Awadh Punch stands as a forgotten yet formidable chapter in India's freedom movement. In an age of fiery speeches and brutal crackdowns, it chose satire. It decided to mock, mimic, and mirror the empire until the emperor looked ridiculous.

It taught us that rebellion doesn't always come wearing a khadi cap or holding a flag. Sometimes, it comes in the form of a magazine that makes the empire chuckle—and then choke.