How a Bengali aristocrat turned a religious celebration into colonial Calcutta’s most flamboyant political theatre—seducing the British with incense, silk, and sovereignty

Durga Puja in Bengal is more than just a festival—it is a declaration of identity, devotion, and pride. But long before it turned into a people's carnival on the streets, it began behind gilded doors as a display of wealth, power, and diplomacy.

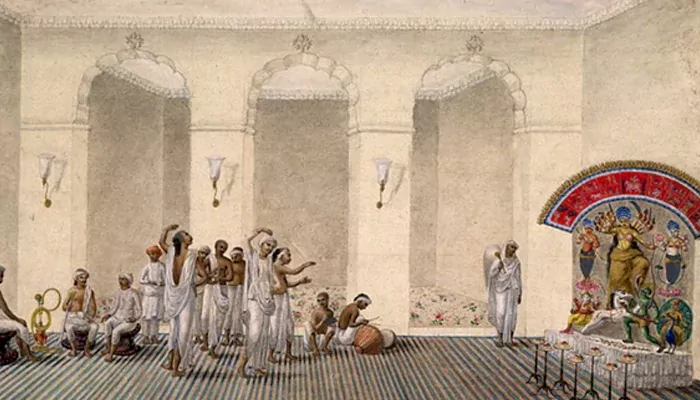

Nothing was more theatrical—or more strategic—than in the vast courtyards of Shobhabazar Rajbari, where Raja Nabakrishna Deb, an ambitious zamindar with a sharp political sense, hosted a Durga Puja that drew the British into cultural submission.

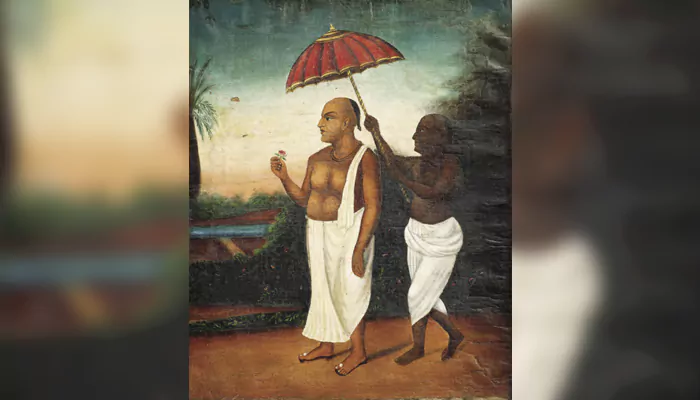

It was 1757. Siraj-ud-Daulah had just been defeated at Plassey, partly due to covert Indian allies. One of them, Nabakrishna Deb, emerged from the shadow of betrayal as a man reborn—wealthy beyond measure and essential to the East India Company. But he desired more than money; he sought recognition. So, that same year, in the newly constructed thakurdalan of his Shobhabazar palace, he inaugurated a Durga Puja not merely for the gods but also for the Empire.

He invited Robert Clive, Warren Hastings, and an assembly of British officers to the puja—an unprecedented act in colonial India. For the British, it was a spectacle of the exotic; for Nabakrishna, it was a form of statecraft in disguise. The British were not just spectators, but key participants in this cultural event, which was a strategic move by Nabakrishna to gain their recognition and favour.

(Credit: Wikipedia)

This was no humble village worship. There were nautch girls, elaborate banquets, poetic jousts, and orchestras playing deep into the night. Silk, sandalwood, and silver flowed through the halls. It wasn't just a celebration; it was a meticulously choreographed overture of loyalty—to the Goddess and the Crown.

The puja became a template for Bengal's landed elite. Over the following decades, Durga Puja evolved into an elite cultural spectacle. Organising such a celebration was less about devotion and more about signalling political influence and proximity to the ruling class. It was, in effect, the Bengali babu's way of declaring: I belong to the future.

What's remarkable is that the legacy endures. Today, Shobhabazar Rajbari still hosts two separate Durga Pujas—one in the boro pakhsha (at 33 Nabakrishna Street) and another in the chhoto pakhsha (at 36). Both are rich in memory. The ornate thakurdalan still welcomes thousands of visitors, the air still filled with marigolds and centuries-old gossip.

But beyond the rituals, Shobhabazar Rajbari is a place where India's complex relationship with the British took shape. It's a relationship that was never simply about resistance or collaboration, but about carefully planned choreography, a dance of power and influence.

(Credit: India Today )

Raja Nabakrishna Deb may not comfortably fit into nationalist histories. He was not a rebel. His rise was connected to the decline of Indian sovereignty. However, to dismiss him is to overlook the complex ways Indian elites navigated power during an age of conquest. He did not oppose the British with weapons—but he mastered the art of symbolic influence.

He built temples, hosted philosophers, sponsored classical music, and established cultural institutions that would endure long after him. His adopted son, Gopi Mohun Deb, and grandson Radhakanta Deb went on to become leaders in education and social reform. The mansion that once celebrated the East India Company would later host Swami Vivekananda after his triumph at Chicago.

In a Kolkata filled with pandals and pop idols, Shobhabazar Rajbari remains steady—weathered but unbowed. Every October, as the drums start to beat and the dhunuchi smoke permeates the air, the echoes of history stir quietly within its walls.