Let's understand why this 400-year-old dome still leaves visitors in awe.

If you’ve ever stepped into the grand hall of Gol Gumbaz in Bijapur, chances are you paused mid-step, partly because of its sheer scale, and partly because you heard something unexpected: your own voice bouncing back to you. Or maybe someone’s murmur from the other side of the dome reached your ear like a soft echo. That’s the magic of this 17th-century monument, where architecture and acoustics blend in ways that still baffle modern minds. Built by Sultan Mohammed Adil Shah as his final resting place, Gol Gumbaz is a marvel of sound, space, and symmetry. And its whispering gallery has turned curious visitors into awestruck listeners for centuries. But why did a ruler go to such lengths to build a dome where even a soft sigh travels across 144 feet? Well, this story dives into the mystery of one of India’s most fascinating monuments.

In the early 1600s, Bijapur was thriving. Under the Adil Shahi dynasty, this Deccan city pulsed with life, as Persian poets recited verses in its courts, Turkish-inspired domes rose against the skyline, and local artisans left their mark in stone and stucco. Mohammed Adil Shah ascended the throne in 1627, just 15 years old and full of ambition.

His father, Ibrahim Adil Shah II, had already raised the bar with the exquisite Ibrahim Rauza, a tomb so elegant it was often compared to the Taj Mahal. But Mohammed wasn’t content living in that shadow. So, even before officially becoming Sultan, he commissioned a monument that would surpass his father's: a structure that would be larger and unforgettable. Construction of the Gol Gumbaz began in 1626, and though Mohammed died before its completion in 1656, the monument became a symbol of his aspirations.

But this wasn’t only about one-upmanship. Bijapur, though smaller than the Mughal Empire to the north, was determined to hold its own. Gol Gumbaz was as much a political statement as a personal one, being a reminder that the Adil Shahis were still a force. Some accounts suggest that Mohammed was deeply influenced by the Sufi saint Hashim Pir, whose dargah sits just behind the mausoleum. That spiritual connection may have shaped his desire to create a space where the divine could be heard.

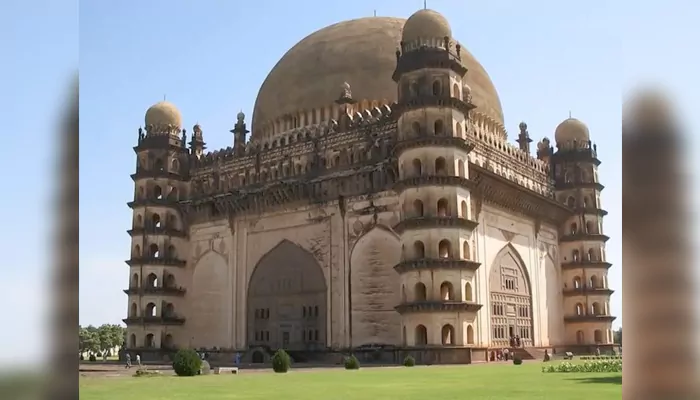

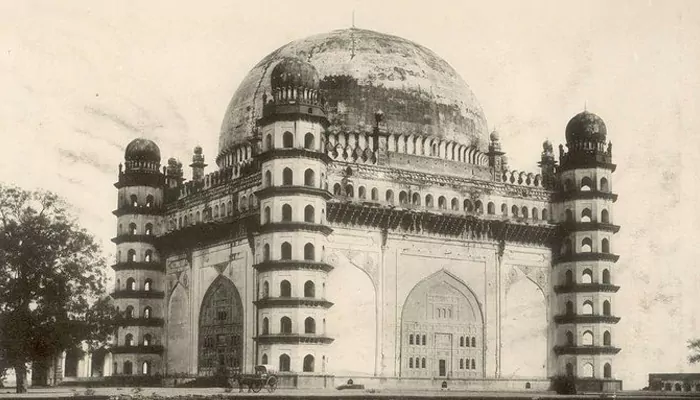

Gol Gumbaz is jaw-droppingly, gravity-defyingly massive. Built from dark grey basalt and finished with lime plaster, the tomb’s dome spans an incredible 44 meters, making it one of the largest in the world before the modern era. Unlike many domes that rely on internal supports, this one stands free, thanks to an intricate system of interlocking arches and pendentives that shift the weight outward.

The square base is almost 50 meters on each side, housing a main chamber of over 18,000 square feet. At each corner stands an octagonal tower, seven stories high, with winding staircases that offer panoramic views of Bijapur’s dry, red-soiled landscape.

But the most remarkable feature lies at the base of the dome: a circular corridor known as the whispering gallery. Here, the architecture turns into alchemy. Even the softest sound (a sigh, a footstep, or a murmured word) travels around the dome and returns like a sonic boomerang. The tomb’s architect, Yaqut of Dabul, didn’t leave behind blueprints or inscriptions, but whether by meticulous design or sheer brilliance, he created something acoustically extraordinary.

Step into the whispering gallery and speak. Your voice, no matter how low, skips along the curved surface and returns to you from across the dome. A simple clap repeats in a sequence, each reverberation trailing off like a fading chorus. Even the ticking of a watch can reportedly be heard from the opposite side.

Architectural experts credit this to the gallery’s elliptical shape and the finely polished surfaces of the walls. These help focus and reflect sound waves with remarkable precision. While other buildings, like London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral, also have whispering galleries, Gol Gumbaz’s is open to all and engineered on a much grander scale.

Tourists today still test the acoustics, giggling as their whispers come back multiplied. Local guides demonstrate with chants, songs, and claps, transforming the silent tomb into a chamber of echoes.

So why would a sultan design a resting place that amplifies sound? Some theories suggest practicality; perhaps the gallery allowed guards to eavesdrop on whispers below, an early form of acoustic surveillance in a court teeming with intrigue. But more compelling is the spiritual interpretation.

In Sufi philosophy, sound is sacred. Chanting, prayer, and music are often seen as pathways to the divine. It's possible that Mohammed Adil Shah, influenced by mysticism, envisioned his tomb as more than a grave and saw it as a resonant bridge between the earthly and the eternal. The dome, symbolizing the heavens in Islamic architecture, becomes a space where words (especially prayers) could rise and reverberate forever.

Of course, the political angle can’t be ignored. Constructing a dome of this scale, unsupported by columns, was a statement of sheer technical prowess. It was also, in many ways, a bold challenge to the Mughals, making a declaration that Bijapur’s architects could rival the best in Hindustan.

Gol Gumbaz still commands attention today. Now maintained by the Archaeological Survey of India, it remains a top attraction in Vijayapura (formerly Bijapur). The complex includes a mosque, a rest house, and a museum featuring artifacts like bidriware and ancient manuscripts. One curious relic sits at the entrance, a chunk of meteorite, dubbed the “Bijli Pathar,” believed by some locals to protect the monument from lightning.

Visitors often climb the steep tower steps, catching their breath at the top and then losing it again as their whispers swirl through the dome. One recent visitor summed it up perfectly: “It feels like the walls are talking back.”

Time, of course, hasn’t left Gol Gumbaz untouched. Cracks have appeared, and foot traffic wears down the stone. Conservation efforts are ongoing, yet the structure endures, drawing historians, architects, and curious travelers alike. Acousticians still study its sound behavior, marveling at how such precision was achieved with 17th-century tools.