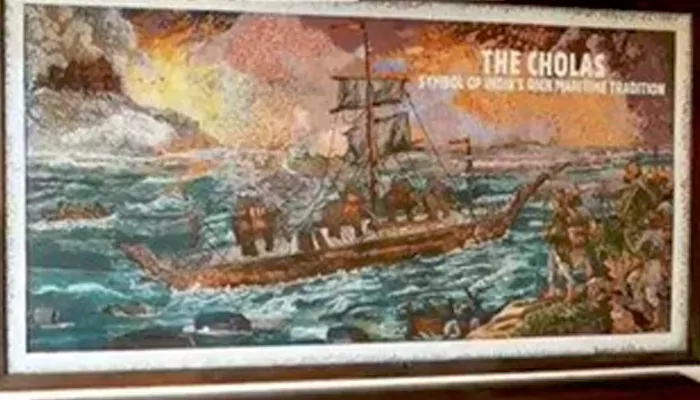

When South India Had a Naval Power That Ruled the Seas - The Chola Empire’s Forgotten Armada

- Sayan Paul

- 6 months ago

- 7 minutes read

Long before colonisers came by sea, the Cholas were already ruling it.

If you’ve read about the Cholas, or even just watched Mani Ratnam’s 'Ponniyin Selvan', you probably know they were one of the most powerful dynasties in Indian history. Their grand temples, fierce warriors, and legendary rulers like Rajaraja and Rajendra Chola often take the spotlight. But what many don’t realize is that the Cholas weren’t just land conquerors; they were also masters of the sea. Yes, long before European powers began dreaming of overseas empires, the Cholas had already built one. With a strong navy that sailed across the Indian Ocean, they launched expeditions as far as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and even Southeast Asia. Besides the soldiers, their ships carried everything from culture to trade and more, reshaping the regions they touched.

This is the forgotten story of the Chola armada, India’s ancient sea power that ruled the waves and left a legacy that the world has all but erased.

The Rise of a Sea-Bound Empire

The Cholas, who rose to power in Tamil Nadu’s fertile Kaveri delta, were naturally poised for maritime dominance. Their proximity to the Coromandel Coast and the region’s long-standing trade connections meant they were no strangers to the sea. By the 9th century CE, South India was already a bustling node in international commerce, with its ports buzzing with spices, pearls, fine textiles, and goods bound for markets in the Middle East and beyond.

But with wealth came threats. Pirates prowled sea routes, and regional rivals like the Cheras and Pandyas often disrupted trade. Recognizing the sea as both a lifeline and a vulnerability, the Cholas responded with force. They built a navy not just to defend but to dominate.

Nagapattinam emerged as the nerve center of Chola shipbuilding. Here, craftsmen built enormous teakwood vessels (called kalam and dhonis), some believed to stretch over 100 feet in length. These weren’t simple merchant boats; rather, they were floating fortresses, capable of withstanding rough monsoons and carrying soldiers, supplies, and even war elephants. Strategic ports like Kaveripattinam (modern-day Poompuhar) and Mamallapuram were transformed into fortified naval hubs, equipped with docks, granaries, and garrisons.

The navy itself was no ragtag force. It operated under a clear hierarchy, with admirals (nāvāyakas) at the helm and a support system in place for logistics, maintenance, and crew training. Inscriptions found at the Brihadeeswara Temple in Thanjavur hint at a well-oiled maritime bureaucracy, suggesting that naval planning and deployment were integral to the empire’s structure, not an afterthought.

Rajaraja and Rajendra: The Ocean-Conquering Kings

The Chola navy truly came into its own during the reigns of Rajaraja Chola I (985–1014 CE) and his son, Rajendra Chola I (1014–1044 CE). Rajaraja, best known for temple-building and administrative reforms, saw the sea as a crucial frontier. Under his command, the Chola fleet expanded aggressively, capturing key ports along South India’s coast and pushing into northern Sri Lanka around 993 CE. The famed Thiruvalangadu copper plates proudly proclaim that his ships crossed the seas to wage war and protect Tamil merchant interests.

But it was Rajendra who transformed the Chola navy into a force that stunned the ancient world.

In 1025 CE, in one of the boldest maritime expeditions in Indian history, Rajendra launched a naval strike against the Srivijaya Empire, based in present-day Indonesia and Malaysia. Srivijaya controlled the vital Strait of Malacca and had begun interfering with Tamil traders. Rajendra's response was a calculated, long-range offensive spanning over 2,000 nautical miles.

Guided by expert navigators using star charts and coastal knowledge, the Chola armada (hundreds of ships strong) cut through unpredictable monsoon currents to reach Southeast Asia. They attacked Srivijaya’s capital, Kadaram (modern-day Kedah), and several other trading ports including Palembang and Tambralinga. Tamil inscriptions, including those at Gangaikonda Cholapuram, list the vanquished cities.

A 1000 years ago (1025 CE), Rajendra #Chola faced a problem. His trading ships were taxed heavily by the Srivijaya empire and faced restrictions. He decided to settle the matter when #diplomacy failed. pic.twitter.com/xWRD7nPGwq

— Indic History (@IndicHistory) July 22, 2025

((Credit: Indic History)

To celebrate this unprecedented feat, Rajendra established Gangaikonda Cholapuram as his new capital, its name (“The Chola who brought the Ganges”) commemorating both his northern and maritime conquests. A temple inscription states, “The king, with his great army and ships, conquered the islands of the sea.” It marked a high point in Indian naval history, a time when an Indian ruler sent warships across oceans to assert control over trade routes and territory.

A Fleet That Carried More Than Soldiers

But the Chola navy wasn’t only about war. It became a powerful vehicle for culture, diplomacy, and most importantly, commerce. Alongside soldiers, Chola ships carried merchants, craftsmen, and Buddhist monks, exporting not only goods but also Tamil ideas, art, and religion.

Across Southeast Asia, Chola influence is visible even today. The architecture of Cambodia’s Angkor Wat draws clear parallels with the Dravidian temple styles of Tamil Nadu. Tamil inscriptions discovered in the Bujang Valley of Malaysia and bronze sculptures in Sumatra echo the Chola aesthetic. Ports like Nagapattinam grew into cosmopolitan hubs, where Tamil merchant guilds such as the Ainnurruvar negotiated deals with Arab traders, Chinese seafarers, and Southeast Asian merchants. They traded pepper, betel nut, and cotton for luxury goods like silk, ceramics, and gold.

Chinese Song dynasty records mention emissaries from the Chola court arriving with tribute, proof that these sea routes were active and respected. Even the Persian polymath Al-Biruni wrote about the wealth and activity of South Indian ports, which were guarded by heavily armed ships.

According to Chola records, it took 84 yamams (a traditional unit of time) — roughly 15 days — for the Chola navy to sail from Nagapattinam to Thalai Thakkolam (believed to be near present-day Krabi, Thailand). En route, they made a stopover at the Nicobar Islands, known then as… pic.twitter.com/FeeLc2oOeg

— 𑀓𑀺𑀭𑀼𑀱𑁆𑀡𑀷𑁆 🇮🇳 (@tskrishnan) July 19, 2025

(Credit: @tskrishnan)

In effect, the Chola navy turned the Indian Ocean into a vast network of influence, which connected the Tamil coast to East Africa, Arabia, Southeast Asia, and China, centuries before Vasco da Gama arrived on Indian shores.

Why We Forgot an Oceanic Empire

So why isn’t the Chola navy front and center in our history books? One reason lies in how Indian history has been traditionally told. For generations, historians focused on northern empires like the Mauryas, Guptas, or Mughals, whose legacies were rooted in land battles, forts, and capital cities. The sea, and those who ruled it, faded into the margins.

British colonial narratives made it worse. Eager to portray themselves as pioneers of maritime prowess in the Indian context, colonial scholars often dismissed or ignored pre-modern Indian naval achievements. The idea that Indian kingdoms were landlocked and static was convenient for imperial propaganda.

There’s also the challenge of evidence. Unlike stone temples or copperplate inscriptions, wooden ships don’t survive the centuries. Oral traditions that might have preserved naval tales eventually faded. And in modern school textbooks, maritime history rarely gets more than a passing mention.

From the available inscriptions, it can be deduced that Chola Navy used three types of Ships namely Marakkalam, Thoni and Kalavam. Marakkalam was the biggest of the three. These warships were built at various places in Palk bay. Nagappattinam was their principal port of… pic.twitter.com/xUxe7SV4iC

— 𑀓𑀺𑀭𑀼𑀱𑁆𑀡𑀷𑁆 🇮🇳 (@tskrishnan) December 4, 2024

(Credit: @tskrishnan)

As a result, even the astonishing naval exploits of the Cholas have remained hidden in plain sight.

Traces That Still Speak

Still, traces of the Chola armada persist... if you know where to look. Copperplate inscriptions like those from Thiruvalangadu speak of fleets “that rode the waves.” Chinese court records describe Chola emissaries with awe. The Nagarakretagama, a 14th-century Javanese poem, recalls Tamil influence in island kingdoms. Archaeological discoveries in places like Kedah (Malaysia), including Tamil inscriptions and Chola-style statues, point to a legacy that extended far beyond India’s shores.

In recent years, historians like Tansen Sen and R. Nagaswamy have helped shine a spotlight on this overlooked chapter. Excavations at ancient port towns such as Nagapattinam continue to reveal artifacts linked to maritime trade. And while Mani Ratnam’s 'Ponniyin Selvan' may take dramatic liberties, it has reignited public interest in the dynasty, including its naval feats.