In the shadows of World War I, Indian soldiers stationed in Singapore sparked a rebellion that revealed the fragile bonds of loyalty in Britain’s colonial forces.

In the early months of 1915, while most eyes were on the muddy trenches of Europe, a rebellion flared in a quiet colonial corner of Southeast Asia. Singapore, a jewel in the British Empire’s Asian crown, witnessed a mutiny that shook the confidence of the colonial powers. On February 15, nearly half of the 5th Light Infantry—a regiment of Indian Muslim soldiers—turned their rifles on the British officers they served. It was short-lived, but it was no ordinary act of defiance.

The roots of the mutiny were entangled in rumour, faith, and the broader politics of war. Many sepoys believed they were being sent to fight against fellow Muslims of the Ottoman Empire, which had entered World War I on the side of Germany. News of the Caliph’s call for jihad had reached their ears, carried by Ghadar Party activists and pan-Islamist whispers. In an era of censorship and slow communication, rumours became reality for soldiers far from home.

In the late afternoon of February 15, four companies of the 5th Light Infantry struck. Officers were shot, the garrison was overrun, and around 800 German prisoners held in Tanglin were freed, though most did not join the chaos. Mutineers moved toward key positions in Singapore, targeting barracks and military installations. British, Malay, and even Chinese volunteers attempted to hold the line, but it took days for order to be restored. The violence spread across parts of the city, leaving dozens dead.

The colonial administration was taken aback. British reinforcements were delayed, but help came from unexpected quarters. French, Russian, and Japanese warships docked in Singapore offered their men to suppress the uprising. It was an extraordinary moment: imperial rivals collaborating to suppress a rebellion against a shared colonial order. By February 20, the mutiny had been quelled. Many mutineers fled into the jungles, but most were rounded up in the following days.

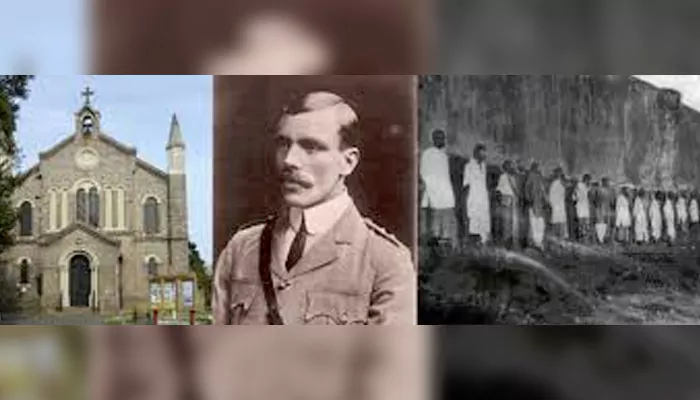

British justice was swift and public. Courts-martial were held, and 47 sepoys were sentenced to death. Executions were carried out at Outram Prison, some of them publicly—a grim spectacle not seen in decades. Others received life imprisonment or transportation to the Andaman Islands. The message was clear: rebellion, even abroad, would be met with brutal certainty. The event forced British authorities to rethink their deployment of Indian troops in the Far East.

Unlike the 1857 Revolt or the later Quit India Movement, the Singapore Mutiny never became a symbol of Indian resistance. Its motives were too mixed, its outcome too chaotic. Yet, it revealed the fragility of colonial loyalties. These were not rebels raised on nationalist slogans, but soldiers torn between duty, faith, and fear. Their revolt was born from confusion of orders, loyalties, and world events unfolding far beyond Singapore’s shores.

Today, few memorials mark the events of that February 1915 week. In Singapore, plaques remember the British and civilians who died, but little is said of the sepoys who mutinied. For India, too, the event sits awkwardly—neither entirely patriotic nor easily dismissed. And yet, the Singapore Mutiny reminds us of an important truth: that even the most distant outposts of empire were not immune to revolt, and that Indian soldiers, even abroad, carried within them the potential to defy the Raj.