The hill still stands... and the graves are still there.

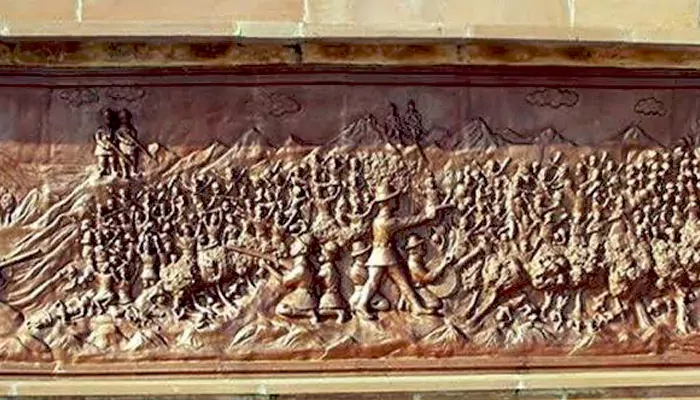

We’ve all heard of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre that became a symbol of colonial cruelty and a spark for India’s freedom struggle. The horror of that April day in 1919, when British troops fired into a peaceful crowd in Amritsar, still hurts us, stirring anger, sorrow, and pride in equal measure. But what if I told you that wasn’t the first? What if, six years before Jallianwala, the British had already carried out a similar massacre, just that it happened far away, on a hill in Rajasthan, and history barely noticed? Yes, in 1913, thousands of Bhil tribals had gathered at Mangarh under the leadership of Govind Guru, seeking justice and reform. And what followed was brutal (to say the least), where hundreds were gunned down.

Yet today, very few know about it. So this is the story of the Mangarh massacre, which is unfortunately a forgotten chapter in Indian history.

Mangarh Hill sits deep in the Vagad region, where the dense forests of Rajasthan brush against Gujarat’s tribal heartland. For the Bhil people, one of India’s largest and oldest tribal communities, this hill was sacred ground. They came here to pray, gather, and speak of freedom.

Historically, the Bhils have lived across Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra, bound closely to the forest. But under British colonial rule and the oppressive practices of princely states like Banswara, Dungarpur, and Sunth, they were pushed to the margins. Land alienation, forced labor, and heavy taxation became a part of their everyday lives. The famine of 1899-1900 only deepened their despair, killing over 600,000 people and forcing many Bhils into bonded servitude just to survive.

Out of this despair emerged a voice of hope: Govind Guru. Born in 1858 in Bansiya village (now in Rajasthan), he came from the nomadic Banjara community. He had worked as a bonded laborer, but later found inspiration in Swami Dayanand Saraswati’s Arya Samaj movement. A self-taught reformer, Govind Guru founded the Samp Sabha, preaching a path of spiritual revival and social upliftment. He urged Bhils to give up alcohol, adopt vegetarianism, and reject social customs that kept them subjugated. But more than anything, he gave them a vision: a Bhil Raj, a tribal society governed by justice and dignity. And at the heart of that dream stood a sacred fire on Mangarh Hill (the dhuni) around which thousands would gather.

By 1908, Govind Guru’s teachings had moved beyond spiritual reform and morphed into a socio-political movement. His followers (mostly Bhils and Garasias) began organizing against forced labor, harassment, and excessive taxation imposed by the princely states and British administrators. In 1910, they submitted a memorandum with 33 demands to the colonial authorities, demanding fair treatment, abolition of bonded labor, and an end to unjust levies.

The ruling powers grew increasingly uneasy. Not only was their authority being questioned, but Govind Guru’s teachings were hitting them financially. With many Bhils giving up alcohol, liquor revenues were falling. A sense of tribal unity was emerging that the princely states had never encountered before.

On November 12, 1913, Govind Guru sent a delegation to negotiate with the British. The response was cold and threatening: disperse from Mangarh Hill by November 15 or face the consequences. But for the thousands camped there, leaving wasn’t an option. The dhuni still burned, and their faith held firm. And they had no weapons, just the conviction that their demands for dignity weren’t criminal.

But the British and princely rulers saw things differently.

The morning of November 17 broke heavy with foreboding. British troops, backed by soldiers from the princely states of Banswara, Dungarpur, Sunth, and the Mewar Bhil Corps, surrounded Mangarh. Machine guns and cannons were dragged up nearby ridges on mules and camels. Then came the order, and a storm of bullets.

Eyewitness accounts describe the horror. Men, women, and children all caught in the line of fire. The Gujarat Forest Department’s official biography of Govind Guru recounts how the cannons were rotated in a circular motion to kill as many as possible. Villager Virji Parghi of Banswara later said his father saw guns mounted on animals, spraying fire in every direction.

The exact death toll is still debated. Some official accounts put it around 500. But oral histories passed down in Bhil families and cited by researchers insist that over 1,500 were killed.

The United Kingdom government must formally apologize to the families of the tribal martyrs who lost their lives in the Mangarh Massacre on November 17, 1913, a tragedy that remains deeply etched in the history of Rajasthan. Over 1,500 innocent tribals were mercilessly killed by… pic.twitter.com/mJo9KW2yOt

— Tribal Army (@TribalArmy) November 17, 2024

((Credit: Tribal Army)

Govind Guru was captured, along with his key lieutenant Punja Pargi and nearly 900 followers. The sacred dhuni had been extinguished by colonial gunfire. And that's how Mangarh Hill, once a sanctuary, became a graveyard.

The massacre at Mangarh barely registered in British reports. While Jallianwala Bagh became a national scandal in 1919, Mangarh was deliberately downplayed. These were “tribals,” after all, seen by the empire as backward and dispensable. There were no editorials in London’s papers, and no outrage in Parliament.

Historian Arun Vaghela, who has studied tribal uprisings extensively, explains: “To the British, the Bhil resistance wasn’t even worthy of serious notice. It was sidelined as a minor disturbance, not a movement.”

Govind Guru was initially sentenced to death, but his punishment was reduced to 20 years in prison. He was exiled to Kamboi near Limbdi in Gujarat after his release in 1919. He died in obscurity in 1931.

Post-independence, the silence continued. India’s mainstream freedom narrative focused on Gandhi, Nehru, and other urban, elite leaders. Tribal revolts have always been pushed aside. “This erasure,” says tribal activist Nilesh Roat, “wasn’t just colonial; it was systemic in the way modern India wrote its history.”

It took decades for Mangarh to claw its way back into public consciousness. In 2017, a long-overdue Tribal Freedom Struggle Museum was proposed at the site. It finally opened in 2022. And on November 1, 2022, Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared Mangarh Dham a national monument, calling it “a chapter of history long ignored, now being corrected.”

But not everyone sees this as apolitical. With elections in tribal-dominated regions, many critics have pointed to the timing of these recognitions. For the Bhils and other tribal communities, official memorials are welcome, but not enough. They seek representation, education, land rights, and inclusion in the national narrative.

Institutions like the Tribal Research Institute in Udaipur and Indira Gandhi Tribal University have begun documenting oral histories, ensuring that survivors’ descendants and their stories aren’t lost. Historian D.N. Thakur, who has written on Adivasi resistance, believes Mangarh is a “monument not only to tragedy, but to tribal resilience.” On social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter), users like @TribalArmy continue to demand that Mangarh be remembered alongside Jallianwala Bagh, not below it.

#UK Government must tender apology & give compensation to families of tribal martyrs of #Mangarh (Gujarat, Rajasthan) for massacre happened on 17 November 1913 (more heinous crime than Jalianwala Bagh) @Adivasibhil1#आदिवासी #adivasibhil

— #adivasibhil (@Adivasibhil1) November 17, 2022

#मानगढ़_भील_शहादत_दिवस pic.twitter.com/Ku1ucOaRZX

(Credit: #adivasibhil) )

Remembering Mangarh isn’t only about mourning the dead. More than that, it’s about restoring dignity to those who died fighting for it. And it’s about ensuring that India’s story includes every corner and every community.