The press laws couldn't choke India's rising tongues

In colonial India, silence was often a strategic approach. The British feared not just uprisings and protests, but words. Especially those written in local languages. Across towns and villages, a new force was taking shape in ink and print. Vernacular newspapers, often handwritten or printed on modest presses, were speaking to the people in their tongues. That terrified the Empire. So, it reached for laws and lathis. But despite years of censorship, intimidation, and control, India's vernacular press refused to be silenced.

In 1878, Lord Lytton introduced the Vernacular Press Act, aimed at muzzling Indian language newspapers. The Act was clear in intent—English newspapers were untouched, but vernacular ones had to face pre-censorship, security bonds, and even shutdowns without trial.

Magistrates were given the authority to shut down publications they deemed "seditious." No appeals. No questions asked. It was a direct attack on voices speaking in Bengali, Urdu, Tamil, Hindi, and other native languages.

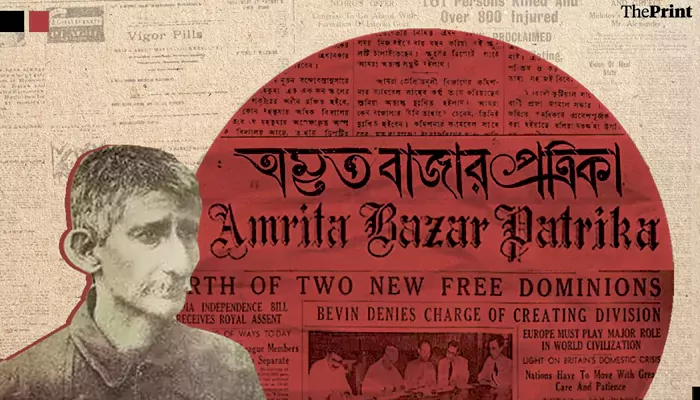

However, the Indian press was not taken aback. One of the most prominent Bengali papers, Amrita Bazar Patrika, swiftly turned into an English-only publication overnight. It was a tactical shift. The message was simple: we will not stop.

Credit -- The Print

Founded in 1868, Amrita Bazar Patrika began as a bilingual publication in Bengali and English. However, when the press laws were implemented, it dropped Bengali and began publishing entirely in English to evade the restrictions.

The newspaper became a symbol of resistance, with its sharp editorials sharply criticising British policies. Others followed suit—shifting languages, using coded messages, or simply risking arrests.

The law had tried to suppress voices, but it gave the Indian press its first taste of defiance. And they liked it.

The power of the vernacular press lay in its reach. English newspapers, while influential, primarily addressed the elite. Vernacular publications, however, reached the ordinary people—the farmers, the artisans, the students.

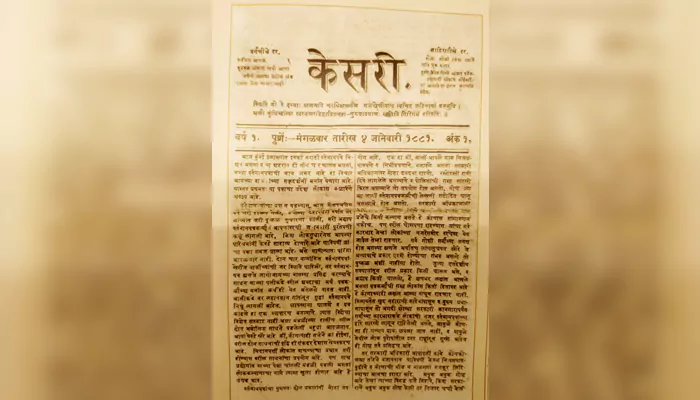

Newspapers like Kesari in Marathi, Swadeshabhimani in Malayalam, and Jugantar in Bengali became platforms for emerging nationalist thought. They questioned taxes, exposed police brutality, and chronicled resistance across provinces.

These papers helped create a shared political consciousness. Readers didn't just consume news—they began to feel part of a larger struggle.

In 1910, as nationalist activities intensified, the British passed another repressive law—the Indian Press Act. It required heavy security deposits from printers and allowed the government to confiscate any publication it deemed objectionable.

More than 1,000 publications were affected. But it didn't stop the movement. Editors went underground. Printers used pseudonyms. Some continued to publish despite the threat of jail. Many young nationalists, such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, emerged from the world of journalism into full-time political activism.

The colonial government underestimated the passion behind India's growing print culture. The press wasn't just about information—it was about identity. India's vernacular newspapers were building something the British couldn't control: a sense of belonging and purpose.

Every suppression bred a new strategy. When the press was banned, pamphlets were circulated as an alternative means of communication. When printing presses were seized, writings were recited in public gatherings. Language became both sword and shield.

In many ways, the British press laws trained India's freedom fighters to be more inventive—and more fearless.

When India became independent in 1947, it carried with it a deeply rooted press culture shaped by resistance. The role of the vernacular press in building a national movement is often understated, but it was vital.

These newspapers connected millions to the freedom struggle. They carried Gandhian thought, news of civil disobedience, and stories of sacrifice. And they did so not in colonial English, but in the voice of the people.

Today, as India continues to navigate questions of language, freedom, and identity, the history of its vernacular press remains a powerful reminder: silence cannot be imposed for long, especially not in a country whose revolution began in ink.