Through rugged passes, weapons and revolution flowed silently into British India

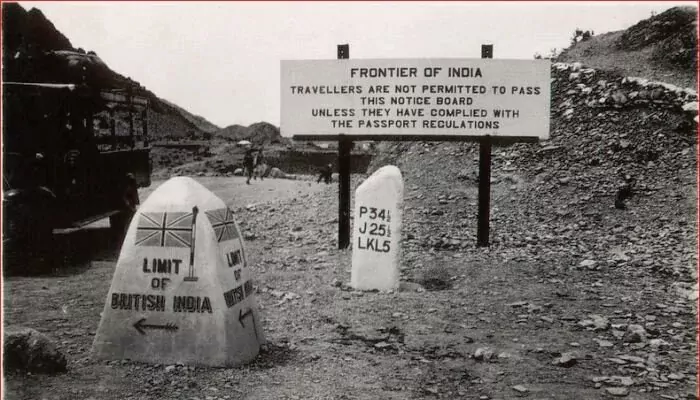

Far from Delhi and Calcutta, in the remote passes of the Northwest Frontier, a quiet storm brewed. Here, amid jagged hills and tribal settlements, a covert system thrived—one that quietly armed resistance against the British Empire. Long before talk of independence became public, guns, gunpowder, and grenades flowed into India from beyond the Afghan border. Not through armies, but smugglers. These were the veins through which revolution pulsed.

While the British ruled India, they never quite controlled its edges. The Khyber Pass, the Kohat trail, the Tirah Valley—these rugged corridors were governed more by tribal honour than colonial law. For the British, it was a buffer zone. For the Pashtun tribes, it was home.

And for revolutionaries, it became a lifeline. These areas offered not just shelter, but networks. Tribes like the Afridis and Waziris, known for their fierce independence, soon became key players in the movement of weapons. They had their reasons: ancestral rivalries, resentment against British intrusion, and a long-standing affinity for firearms that predated the Empire.

The methods were ingenious. Rifles hidden in coffins. Pistols wrapped in textiles. Bullets were smuggled in spice sacks. Arms would enter through Persia or the Russian border into Afghanistan, often originating in Ottoman or German factories. From Afghan towns like Jalalabad or Gardez, camel caravans carried the cargo through secret trails into Waziristan or Tirah.

By the time they reached British India, these weapons had passed through multiple hands. Traders, mercenaries, retired soldiers—even some rogue sepoys played their part. Along the way, they were disguised, dismantled, or sold in parts to local gunsmiths who could reassemble them by lamplight.

In the towns of Darra Adam Khel, Kohat, and Landi Kotal, gun-making became an art form. Long before 3D printers, these workshops reverse-engineered colonial rifles using nothing but metal scraps and memory.

A single British Lee-Enfield rifle, once captured or purchased, could inspire the production of dozens of copies. These weapons weren't perfect. However, they were effective enough to ambush a British patrol or arm a village uprising. Some even ended up with Bengal revolutionaries or Ghadar Party agents, thanks to cross-country routes that linked the frontier to cities like Lahore and Amritsar.

The colonial government was well aware. Intelligence reports from the early 1900s are filled with mentions of "arms infiltration,” "tribal gunsmiths," and "suspicious caravans." But their response was limited.

Terrain, weather, and tribal resistance made it nearly impossible to control the frontier. British officers would often rely on local informants; however, loyalty in the mountains was usually fluid. One day's guide could be the next day's smuggler. Even massive military operations—like the Malakand Campaign or the Waziristan expeditions—failed to dismantle the networks. The arms kept flowing.

The influx of weapons changed the nature of the rebellion. No longer were uprisings sticks and stones. In Punjab, Bengal, and even parts of central India, small revolutionary cells began to arm themselves properly.

During World War I, this pipeline became crucial to the war effort. The Ghadar Party, hoping to ignite a pan-Indian revolt, sought German arms through Persia and Afghanistan. Though most plans were foiled, the idea persisted. Arms were not just tools—they were symbols of defiance.

The Northwest smuggling route didn't topple the British Empire. But it weakened its grip. It armed those who refused to bow. It spread fear in cantonments and forced colonial officers to second-guess their security.

More importantly, it connected India's interior with its outer edges. A gun smuggled through Khyber could end up in the hands of a revolutionary in Howrah or a rebel cell in Pune. That's the story of this hidden artery—connecting mountain passes with dreams of freedom.

In the end, the Empire's borders were never as tight as it thought. And in the silence of those hills, a louder rebellion was born.