The Controversial Rowlatt Act: How Oppression United a Nation

- Sayan Guha

- 5 months ago

- 3 minutes read

How the Rowlatt Act united India in fury and sparked the Gandhian era

March 18, 1919. Delhi’s corridors of power buzzed with hurried debates, but outside, an entire subcontinent braced itself. A new law, shrouded in secrecy and coercion, had just passed: the Rowlatt Act. Dubbed the ‘Black Law,’ it gave colonial authorities sweeping powers to arrest and detain any Indian on mere suspicion, indefinitely and without trial. What followed was more than outrage—it was the ignition of India’s moral and political conscience.

A law that knew no bounds

The Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act, developed from the recommendations of Sir Sidney Rowlatt, extended wartime powers of the Defence of India Act of 1915 into peacetime.

Its clauses deprived citizens of fundamental rights: arrests without warrants, juryless trials, denial of access to evidence, and suspension of habeas corpus. Even the press was placed under strict surveillance, silencing dissenting voices. The law’s purpose was clear—to suppress the rising nationalist movement and intimidate those daring to dream of freedom.

Credit: Britanica

Gandhi hears the call

Mahatma Gandhi, already esteemed for his moral authority, recognised the insidious threat of the act. He understood that opposing it was not merely a political duty but a moral imperative.

On April 6,1919, he called for a hartal—a nationwide strike involving businesses, prayers, fasting, and peaceful protests. Cities and villages across India paused. People from all walks of life, inspired by Gandhi's ethos of non-violence, took to the streets to challenge the injustice without resorting to violence.

From hartals to heartbreak

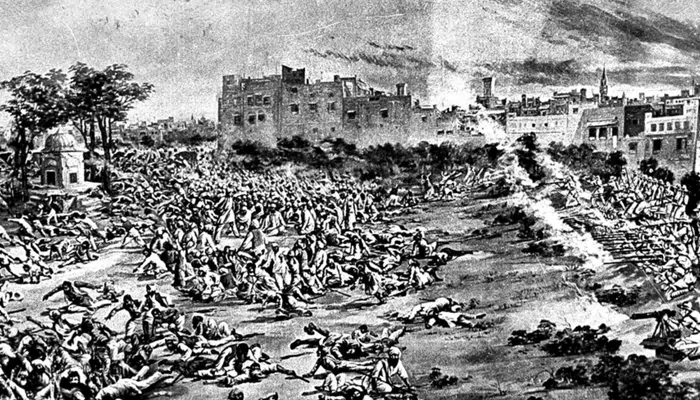

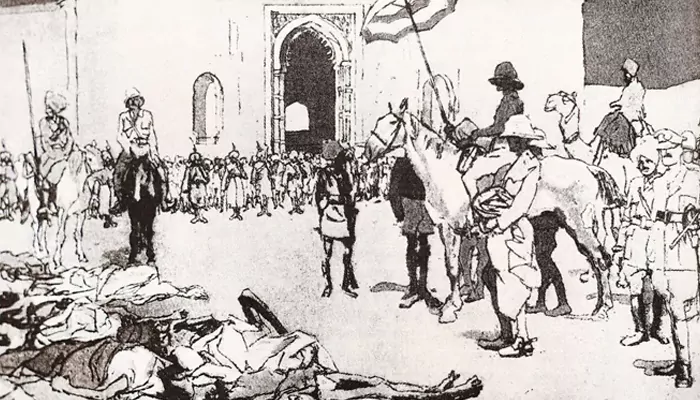

The protests, however, were a double-edged sword. In Punjab, tension escalated sharply. On April 10, the arrests of Congress leaders Dr. Satyapal and Saifuddin Kitchlew sparked mass gatherings during Baisakhi on April 13.

The ensuing army intervention culminated in the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, where hundreds of unarmed men, women, and children were killed. The Rowlatt Act, intended to suppress revolutionary fervour, instead exposed the brutality of colonial rule and seared itself into India’s collective memory.

Credit: Cultural India

A law that backfired

The Rowlatt Act did more than impose oppressive laws—it unified India’s political spectrum. Moderates and radicals, Hindus and Muslims, lawyers and peasants, all expressed their opposition.

Leaders such as Madan Mohan Malaviya, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and Mazharul Haque resigned from the Imperial Legislative Council in protest. Newspapers, temples, and town squares resonated with calls for justice. Gandhi’s voice, calm yet firm, pierced through the noise, exemplifying principled leadership that prioritised action over empty rhetoric.

Legacy of defiance

Although the act remained in effect for three distressing years, its repeal in 1922 signified the triumph of persistent moral resistance.

More significantly, it marked the beginning of the Gandhian era in Indian politics, where civil disobedience, non-violence, and mass mobilisation became powerful tools against colonial rule. The Rowlatt Act, aimed at crushing India’s spirit, instead demonstrated the strength of collective courage and conscience.

Credit: TOI

Remembering the black law

Today, the Rowlatt Act is remembered not for its wording but for the fury it sparked and the awakening it prompted. It serves as a testament to how injustice, no matter how carefully composed, can rally ordinary citizens into extraordinary action. It was a law intended to intimidate—but instead, it set the course for a nation’s march towards freedom.