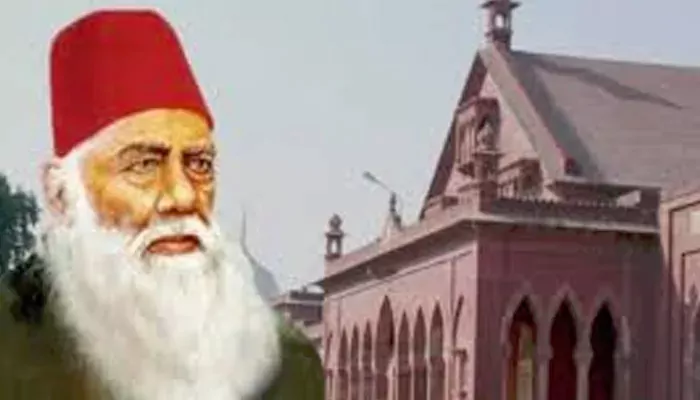

The Aligarh Movement: Sir Syed Ahmed Khan’s Vision for Muslim Education

- Sanchari Das

- 5 months ago

- 3 minutes read

How Sir Syed Ahmed Khan reshaped Muslim identity through science and modern learning

In the nineteenth century, Indian Muslims found themselves at a turning point. After the Revolt of 1857, they were politically weakened and socially cautious. Many hesitated to engage with British institutions or modern learning, fearing it might distance them from faith. Amid this climate, one man—Sir Syed Ahmed Khan—imagined a bold new road. His dream was not only to preserve identity but also to embrace progress. That dream gave rise to the Aligarh Movement, a defining chapter in the history of Indian education.

Laying the Foundations: The Scientific Society

Sir Syed’s first step toward reform was through knowledge. In 1864, he established the Scientific Society of Aligarh, which translated key scientific and literary works from English into Urdu. This effort opened the door for Muslims to engage with modern subjects without feeling alienated from them. Through journals like the Aligarh Institute Gazette, he brought new ideas—on science, governance, and culture—into everyday discussion. It was an attempt to prove that Islam and modern thought could coexist without conflict.

Madrasatul Uloom: A New Kind of School

In 1875, Sir Syed founded Madrasatul Uloom Musalmanan-e-Hind at Aligarh. It was a modest beginning, but soon grew into the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College. The institution stood apart from traditional madrasas. Its curriculum blended English, mathematics, history, and science with Islamic studies and oriental languages. Sir Syed modeled the college after Oxford and Cambridge, aiming to cultivate a generation that could serve with confidence in administration, law, and commerce. The college later evolved into the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), one of India's most prestigious universities.

Building a Wider Movement

Sir Syed knew education had to reach beyond a single college. In 1886, he launched the All-India Muhammadan Educational Conference. The annual gatherings encouraged Muslims across the subcontinent to establish schools and support modern curricula. Earlier, he had also helped establish schools in Muradabad and Ghazipur, laying the groundwork for broader educational reform. His message was consistent: without broad-based education, no community could rise in the modern world.

Facing Criticism and Opposition

The road to reform was not a smooth one. Religious scholars from more orthodox schools accused Sir Syed of diluting Islamic principles. They argued that Western education would erode faith and tradition. Sir Syed responded with pen and patience. Through his journal Tehzibul Akhlaq—the “Mohammedan Social Reformer”—he defended his vision. He argued that Islam encourages the pursuit of knowledge and that rejecting science or rationality was not faith, but fear. His ability to merge religious conviction with progressive thought slowly won supporters.

Legacy of the Aligarh Movement

The impact of the Aligarh Movement extended far beyond one institution. By 1920, the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College became Aligarh Muslim University, a central hub of learning. Its graduates went on to become scholars, administrators, lawyers, and political leaders. More importantly, the movement inspired other institutions—from Dhaka University to Osmania and Jamia Millia Islamia. The ripple effect of Sir Syed’s vision reshaped education for Muslims across the subcontinent. It also helped foster a new political and cultural consciousness that would influence India in the decades ahead.