In colonial Bihar, oppressed farmers turned their granaries into powerful protest art under cover of darkness, whispering rebellion with every brushstroke.

It's the dead of night in rural Bihar, India, sometime around 1917-1918. The air is thick with the smell of wet earth and quiet tension. Instead of sleeping, shadowy figures move silently near village granaries. But they’re not stealing grain - they’re armed with paintbrushes and homemade pigments. Their mission? To defy the crushing weight of unjust taxes imposed by the British Raj in a way that couldn’t be easily ignored or erased.

To get why this happened, we need to feel the farmers' pain. This was Champaran, a region practically choking under the "tinkathia" system forced by British indigo planters. Imagine being told you had to use precious land to grow indigo for them, getting barely enough in return to survive, and then getting slammed with crippling land taxes on top of it? It was brutal. Families were trapped in cycles of debt and despair. They felt utterly powerless against the colonial machinery squeezing them dry.

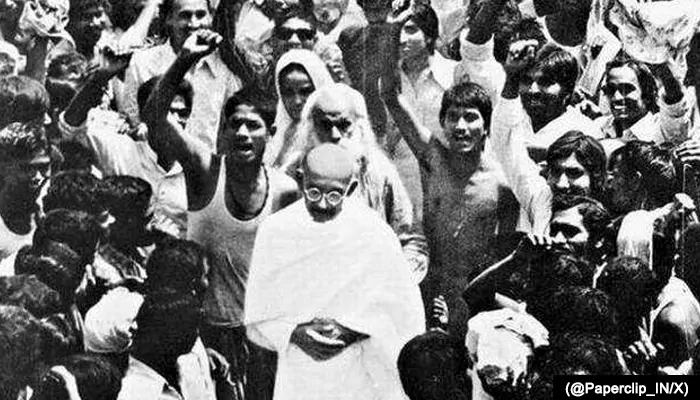

🟠Remembering the indian freedom fighter, Farmer's leader, #RajKumarShukla On His Death Anniversary.

— Jadav Bhadresh RSS (@JadavBhadresh3) May 20, 2023

⚪He led & played an important role in the Champaran Satyagraha movment.

🟢His contribution to Nation's freedom movement & rights of farmers will always be inspire for all of us pic.twitter.com/tyAiY3NB22

Rajkumar Shukla - a Champaran indigo farmer, and Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi - a journalist and freedom fighter were the ones who insisted Gandhi visit Champaran.

(@JadavBhadresh3/X)

It was the year 1917, in Champaran, Bihar. Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi, a journalist, scholar and freedom fighter and Raj Kumar Shukla, an indigo farmer from Champaran, insisted that Gandhi visit. 2/19 pic.twitter.com/cn0o9FUn20

— The Paperclip (@Paperclip_In) October 2, 2022

Champaran Indigo Farmers at work

(@Paperclip_IN/X)

Enter Mahatma Gandhi. His first major Satyagraha in India kicked off right here in Champaran in 1917. He listened to the farmers, documented their suffering, and began organizing peaceful resistance. But how do you keep the spirit of defiance alive when direct confrontation is dangerous? How do you show solidarity across scattered villages?

The farmers found a genius, quiet answer: Wall Art.

Under the cloak of darkness, groups of villagers would gather. Guided by local artists or simply their own sense of injustice, they’d transform the blank, mud-plastered walls of their granaries - the very structures holding the grain taxed into oblivion - into powerful canvases. What did they paint?

The Face of Hope

Images of Gandhi himself, often depicted as their savior ("Gandhi Baba").

#ThisDayInHistory

— National Archives of India (@IN_Archives) April 10, 2025

On 10 April 1917, Mahatma Gandhi launched the Champaran Satyagraha against the exploitation of indigo farmers.#NAI shares a telegram (11 April 1919) reporting unrest in Bihar & other regions, highlighting Gandhi’s growing influence.

-PA, HFM, VII, S. No.10/2 pic.twitter.com/7kdDjLkL4K

10 April, 1917: Mahatma Gandhi spearheaded Champaran Satyagraha against the exploitation of indigo farmers.

(@IN_Archives/X)

Symbols of Resistance

Simple but potent symbols like the Charkha (spinning wheel, representing self-reliance and the Swadeshi movement) and the Congress flag.

Scenes of Struggle

Sometimes, depictions of their own plight - the suffering farmer, the oppressive planter.

Gandhi reached Champaran to investigate and eventually oppose the Teenkathia contractual system through which British planters compelled farmers to grow indigo. 3/19 pic.twitter.com/2933LDjIEp

— The Paperclip (@Paperclip_In) October 2, 2022

A Mural

(@Paperclip_IN/X)

Slogans of Unity

Phrases urging non-cooperation and unity against the tax collectors.

This wasn't just graffiti; it was strategic, emotional communication. Done at night, it minimized the risk of immediate arrest. Painting on the granaries themselves? That was a direct, symbolic slap in the face to the tax system stealing their harvests. Every morning, these vibrant murals would appear like sudden declarations of courage.

After 100 years of Champaran, lessons from the struggle still hold good. #Farmers #Organise #Unite https://t.co/rujokck4rL pic.twitter.com/kNFeZ0pMiF

— Sitaram Yechury (@SitaramYechury) April 11, 2017

Champaran Indigo Farmers at Work

(@SitaramYechury/X)

Think about what these midnight murals meant. For the villagers painting them, it was an act of immense bravery. Getting caught could mean severe punishment. But the act itself was empowering. It transformed fear into collective action, even if silent.

For the wider community, seeing Gandhi's image or the Congress flag appear overnight was electric. It was a visual whisper passed from village to village: "You are not alone. The movement is here. Resist." It signaled solidarity without a word being spoken. It kept the embers of resistance glowing brightly between Gandhi's visits and larger meetings. In a time of widespread illiteracy, these images spoke a universal language of defiance and hope.

The British authorities? They were flummoxed. How do you stop paintings that appear like magic in the night? Erasing them was futile - they’d often just reappear. It was non-violent resistance at its most creative and persistent, deeply rooted in the local culture.

The Champaran Satyagraha, or the movement of Indigo farmers, became a historic movement in the Indian freedom struggle as the British were forced to accept the demands of agitating farmers. 5/19 pic.twitter.com/LdNlrjGDVM

— The Paperclip (@Paperclip_In) October 2, 2022

Champaran Satyagraha: A success in resolving the plight of indigo farmers under British rule.

(@Paperclip_IN/X)

The Champaran Satyagraha was a turning point, proving the power of organized non-violent protest in India. While the indigo system crumbled under the pressure, and the specific midnight mural campaign naturally evolved as the freedom struggle grew, its impact was profound.

Those farmers weren't trained artists. They were ordinary people pushed to the brink. Yet, with simple tools and immense courage, they used art as a weapon against oppression. Their midnight murals were more than decoration; they were heartbeats of defiance painted onto the very fabric of their hardship.

Champaran farmers remind us that sometimes, the most powerful revolutions aren't just shouted from rooftops; they can be whispered onto walls in the quietest hours, speaking volumes through color and symbol. It’s a testament to the incredible, often quiet, creativity that fueled India’s long walk to freedom.