When London became the secret lab of empire's enemies—How Indian and Irish freedom fighters forged an unlikely brotherhood in the belly of the beast.

At the dawn of the 20th century, London was not just the seat of British power—it was also a gathering point for those who dreamed of breaking it. Among them were revolutionaries from two distant colonies: India and Ireland. They walked the same streets, read from the same libraries, and often met in the same rooms. In that imperial capital, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and Roger Casement—figures worlds apart in origin—found themselves in ideological alignment. Their missions were not the same, but their enemy was the same.

In 1905, an Oxford-educated Indian barrister named Shyamji Krishna Varma set up India House in Highgate. It was initially intended to house Indian students, but soon it evolved into something more substantial. Pamphlets, speeches, and coded letters flew out from its rooms. It attracted radical minds, such as Madan Lal Dhingra and Vinayak Savarkar.

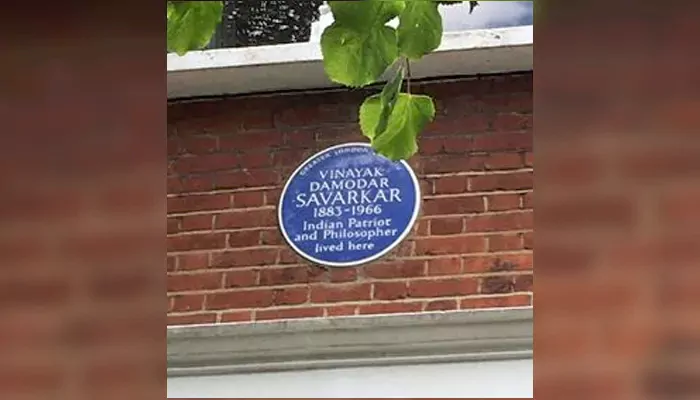

Savarkar arrived in London in 1906. A brilliant student of law and history, he quickly became the intellectual engine of India House. His speeches urged Indians to look beyond petitions and embrace revolution. He translated nationalist tracts and secretly distributed bomb-making manuals. His 1909 biography of Italian rebel Mazzini wasn't just history—it was a call to arms.

India House also became a magnet for other revolutionaries, including Irish nationalists. Bonds were forged quietly, away from the public gaze.

Savarkar's vision was global. He believed colonial liberation could not happen in isolation. Through private gatherings and discussion circles, he met revolutionaries from Egypt, Turkey, and most importantly, Ireland.

In these meetings, Savarkar encountered Irish nationalists who, like him, rejected constitutional appeals to the Crown. Among his early Irish contacts were students, writers, and members of Sinn Féin studying or exiled in London. Their conversations were often philosophical but occasionally strategic.

Roger Casement, once a decorated British diplomat, had travelled through Africa and Latin America and seen the cost of empire. What began as reformist indignation soon turned into radical nationalism. By 1913, he had become one of the leaders of the Irish Volunteers.

Casement resigned from the Foreign Office and went to Germany during World War I. There, he plotted with the Kaiser's government to secure weapons for an Irish uprising. But Casement wasn't just thinking of Ireland. He explored ways to connect with Indian revolutionaries who also had networks in Berlin.

The dream? A joint anti-British insurrection, supported by German arms.

In the chaos of World War I, Indian and Irish revolutionaries tried to strike while the empire was distracted. The Hindu–German Conspiracy saw Indian nationalists from Berlin, California, and Singapore attempting to incite mutiny within the British Indian Army. Casement, meanwhile, sought Indian prisoners of war in German camps, hoping they might join the fight.

Though these plans largely failed, they revealed a startling truth: rebels in Ireland and India were not alone. They were watching each other, writing to each other, sometimes even conspiring together.

The link between the Irish and Indian freedom movements deepened over time. In 1920, Irish soldiers of the Connaught Rangers mutinied in India in protest against British actions in Ireland. They were quickly crushed, but their revolt stirred nationalist pride in both countries.

Later, Indian leaders, such as Nehru, openly admired Irish independence. Irish leaders like Eamon de Valera publicly condemned British violence in India. Their struggles were different in shape but identical in spirit.

For both India and Ireland, London was where ideas sharpened and alliances began. It was in those libraries, pubs, and town halls that the empire's subjects began to imagine a world without it.

Savarkar would eventually be arrested and sent to the Cellular Jail in the Andamans. Casement would be captured and hanged in 1916 for treason. But their stories—and the brief but powerful alliance between Irish and Indian radicals—remind us that empires fall not just from rebellion at home, but from quiet plots abroad.

London gave the world many things. Among them: revolution.