Debunking the Taj Mahal Myth: Did Shah Jahan Really Cut Off His Workers’ Hands?

- Sayan Paul

- 5 months ago

- 4 minutes read

Did the hands that built the Taj really pay the ultimate price, or is it just a story etched in folklore?

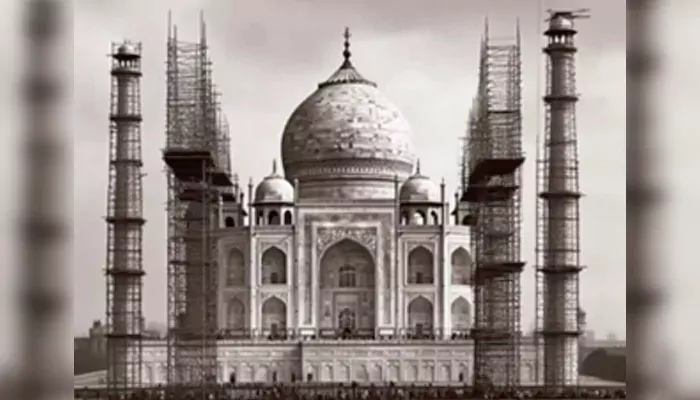

When a story survives for centuries, we take it as truth, not because history always backs it up, but because it’s fascinating to believe. The tale tied to the Taj Mahal is that Mughal emperor Shah Jahan ordered the hands of its workers to be cut off, ensuring no one could ever create something so magnificent again. It’s obviously a chilling image, and perhaps that’s why it stays in our collective memory. And the myth adds to the monument’s aura of mystery and grandeur, making the marble glow with more than just beauty. However, pause for a moment and ask, how much of this is real? Did Shah Jahan really commit such an act, or is this just a legend embroidered over time to make the Taj Mahal’s story more dramatic?

In this piece, we’ll peel back the layers of myth and memory to uncover what history actually tells us about this tale.

The Legend’s Shape

The rumor usually begins in 1648, the year the Taj was completed. Twenty thousand workers, so the story goes, were mutilated to prevent imitation. Sometimes the punishment is a gag order, sometimes a blinding, and other times execution. And in every telling, the emphasis is on the emperor’s jealousy of his own creation. Just like that, the myth transforms an act of devotion into a warning about power and possession.

Tracing Its Roots

Now, the surprising truth is that no Mughal record mentions such a thing. Neither do the Europeans who walked through Agra in the decades after the Taj was finished. In fact, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a French gem merchant, described the costs of the mausoleum in detail, but never suggested cruelty. François Bernier, who traveled with the Mughal court, praised its beauty but made no mention of mutilated workers.

The idea surfaces much later, in the 19th century, by when colonial writers often painted the Mughals as despotic, contrasting their supposed barbarity with European “enlightenment.” Folktales from other lands may also have fed the myth. Russian accounts speak of blinded architects of St. Basil’s Cathedral, while Middle Eastern stories tell of imprisoned builders to protect royal secrets. Such motifs, repeated often enough, attach themselves easily to monuments. In Agra, tour guides in the 20th century began repeating it, adding drama for their audiences. And obviously, Bollywood scripts and political speeches later revived it, ensuring the tale never quite faded.

What the Records Actually Show

See, the Mughal court was nothing if not meticulous. Abdul Hamid Lahori’s Padshahnama, the official chronicle of Shah Jahan, devotes many pages to the Taj. It lists supervisors, architects like Ustad Ahmad Lahori, and the guilds that supplied craftsmen. What it does not list, however, is any punishment. On the contrary, it records wages, material orders, and the vast sums poured into the project.

Surviving farmans (imperial orders) show artisans continued their work after the Taj. Amanat Khan, the calligrapher who carved its Quranic inscriptions, later signed other commissions before dying a natural death. Shah Jahan’s reign also saw the Red Fort and the Jama Masjid rise, built by many of the same craftsmen. It would have been really folly to disable them, both economically and politically. Under Islamic law of the period, amputation was a punishment for theft, and never for skilled labor. Had Shah Jahan issued such a decree, it would have been extraordinary enough to be recorded. But the point is that it was not.

The Historians’ Verdict

Modern scholarship leaves little doubt about the same. Ebba Koch, the leading historian of Mughal architecture, calls the severed hands story nothing more than a “guides’ tale.” Giles Tillotson dismisses it outright, pointing to the continued careers of the craftsmen. Catherine Asher, writing on Mughal architecture more broadly, emphasizes systems of patronage, and not cruelty. The silence of contemporary sources, especially Europeans who were quick to criticize the Mughals when they could, speaks volumes.

Why the Myth Persists

So, if the story is false, why has it survived so long? Part of the answer lies in the psychology that tragedy sharpens awe. A tale of sacrifice, even imagined, deepens the monument’s aura to a great extent. Colonial writers found it useful to dramatize Mughal “despotism.” Tour guides discovered it kept visitors’ attention. And obviously, modern politics occasionally resurrects it as a contrast, casting the Mughals in a darker light.