What Was South India’s Story, While the Indus Valley Thrived Up North?

- Sayan Paul

- 3 months ago

- 5 minutes read

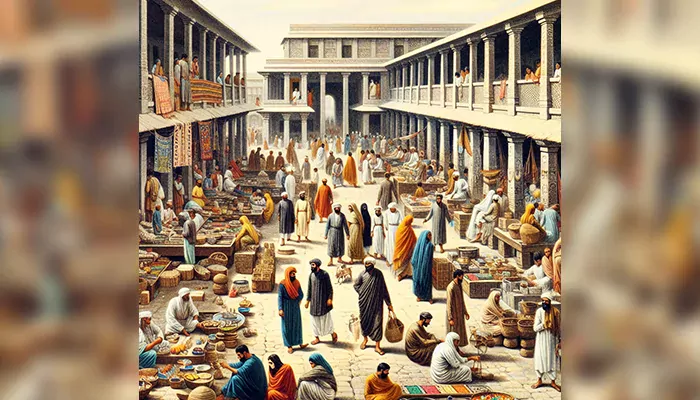

A journey into South India’s life and legacy during the Indus Valley era.

The Indus Valley Civilization flourished across present-day northwest India and Pakistan, covering regions along the Indus River and its tributaries. From around 2500 BCE to 1900 BCE, great cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-daro thrived with advanced urban planning, trade networks, and cultural sophistication. Now, if we look at the subcontinent as we know it today, this civilization dominated the northern landscape. And this naturally brings us to an interesting question. While an organized civilization was in the north, what exactly was going on in the south? Was it empty, or was it slowly building its own story? And if there were people and cultures there, did they have any contact with the Indus Valley?

In this article, we step back thousands of years and explore what history and archaeology reveal about the South’s parallel world in the age of the Indus Valley.

A Quick Glance Northward

At its height between 2500 and 1900 BCE, the Indus Valley Civilization, as already mentioned, spread across parts of modern Pakistan and northwest India. Some of its cities held up to 40,000 people, and it was quite a carefully crafted life there. The economy combined farming (especially wheat, barley, and pulses) with herding and far-reaching trade. Indus beads, cotton, and pottery reached the Persian Gulf and beyond. Their craftsmanship was very precise, while their urban planning was incredibly striking.

Indus Valley Civilisation (c. 2500 BCE - 1900 BCE) pic.twitter.com/bmsacmaASf

— Yadu (@Yaduvam) March 15, 2025

(Credit: Yadu)

South India in the Indus Age

Between 3000 and 1400 BCE, South India moved through its Neolithic phases. Around 2900 BCE, communities were turning from foraging to a mix of herding and farming. They domesticated cattle, cultivated hardy millets like browntop, and lived in clusters of huts on granite outcrops. And by 2500 BCE, dozens of such settlements dotted northern Karnataka and western Andhra.

Life centered mostly on cattle. Zebu were valued not only for milk but also for dung, which dried into fuel. Periodically, villagers built great fires of dung and wood, leaving behind vitrified ash mounds. These seem to have been communal rituals, perhaps linked to fertility or seasonal gatherings. Burials were plain, bodies stretched out in pits with a pot or two beside them, foreshadowing the more elaborate megalithic graves that would appear after 1200 BCE.

These were small and egalitarian groups, perhaps a hundred people in a settlement. Crops were primarily rain-fed. Metal was scarce, though by about 2000 BCE, there were traces of early copper use. Iron would come much later. What matters is that this Neolithic culture grew out of local traditions, meaning it did not descend from the Indus, nor from any northern diffusion.

What the Sites Reveal

Excavations give texture to this world.

At Sanganakallu in Bellary district, Karnataka, archaeologists have uncovered a hilltop settlement active between 2200 and 1400 BCE. There are grinding stones for millets, quarries where dolerite was split into axe-heads, and radiocarbon dates from charred seeds that anchor the timeline.

Nearby, the Kudatini ashmound has been dated to between 2300 and 2000 BCE, a monument to those cattle-burning rituals.

Hallur, on the Tungabhadra River, adds another layer. Excavations in the 1960s revealed Neolithic floors with cattle bones and millet grains, later confirmed by updated radiocarbon assays to around 2300-1800 BCE. Its pottery shows scratches and graffiti marks (rudimentary symbols), but is far removed from the polished Indus script.

(Credit: Journeys across Karnataka)

At Brahmagiri, Mortimer Wheeler’s famous 1947 dig uncovered a sequence from Neolithic pits to early megaliths. Stone celts, beads, and pottery suggest a steady evolution. Dates place the Neolithic occupation around 2400-2100 BCE.

In Andhra Pradesh, Utnur produced another massive ashmound, with bones of cattle, sheep, and goats, dated to 2200–1900 BCE.

Across these sites, the pattern is consistent. It's always local crops and local tools, and no luxuries from the north. Although a stray copper fragment at Hallur hints at contact, its source is still debated.

Now, Were the Two Worlds Linked?

This is where speculation begins. The Vindhya mountains and the Deccan plateau created barriers, but trade routes along rivers or coasts could have bridged the gap. Some have suggested that carnelian beads in the Indus might have come from southern agate, though most are traced to Gujarat. A single etched bead of Harappan style at Piklihal suggests a flicker of contact, but one artifact does not prove steady exchange.

What is undoubtedly striking is the absence. There are no Indus seals and no standardized weights, and not to mention, no wheel-thrown painted pottery in southern sites. The everyday material cultures were different.

Scholars have debated whether later Tamil traditions remember things of northern migrations after the Indus decline, but the evidence is really slender. More likely, if there were connections, they passed indirectly, through intermediary cultures of the Deccan, or through perishable goods like spices, cotton, or timber that leave no trace in the soil. Future techniques, such as isotope studies on bones, may tell us more about movement and diet, but for now, the story leans toward cultural isolation.

To set South India’s Neolithic alongside the Indus cities is not to rank one above the other. It is to see how diverse the roots of Indian civilization really were back then.