The Revolution on a Stage: How Theatre Became Bengal’s Weapon Against the British

- Sanchari Das

- 6 months ago

- 3 minutes read

The play that made planters panic and the people rise

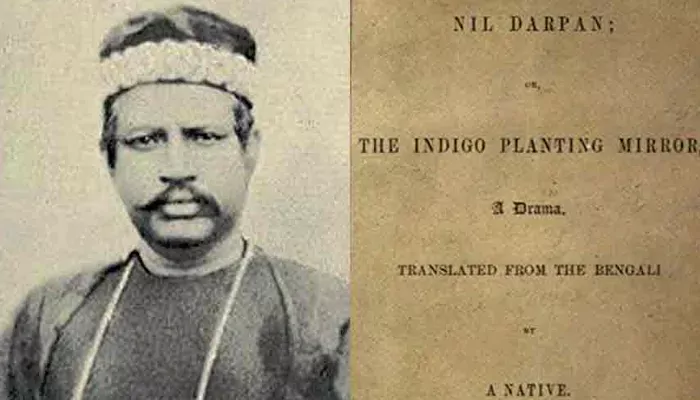

In the late 1850s, Bengal’s countryside was boiling with rage. Indigo planters—mostly British—were exploiting farmers, forcing them into unprofitable contracts, and punishing them for disobedience. Amid this crisis, a Bengali civil servant named Dinabandhu Mitra wrote a play that would shake the very foundations of colonial theatre.

Nil Darpan, or The Indigo Mirror, wasn’t just a play—it was a cry of protest. Written in 1858–59 and published in 1860, it exposed the violent oppression faced by indigo cultivators. The story wasn’t abstract. It was raw, close to reality, and impossible to ignore.

When protesters wore makeup and took the stage

The British didn’t expect the theatre to challenge their power. After all, most performances in Calcutta’s playhouses were adaptations of Sanskrit epics or Shakespeare. But Nil Darpan broke that mould.

In 1872, the play was staged at the National Theatre in Kolkata, marking the first time a Bengali drama took a direct shot at the British establishment. Characters in the play weren’t veiled metaphors—they were planters, peasants, and police. The dialogues were fiery, local, and unsettlingly familiar.

The audience was stunned. Many wept. Some clapped through their tears. But British officials in the crowd were less impressed—they were furious.

The Englishman who printed the rage

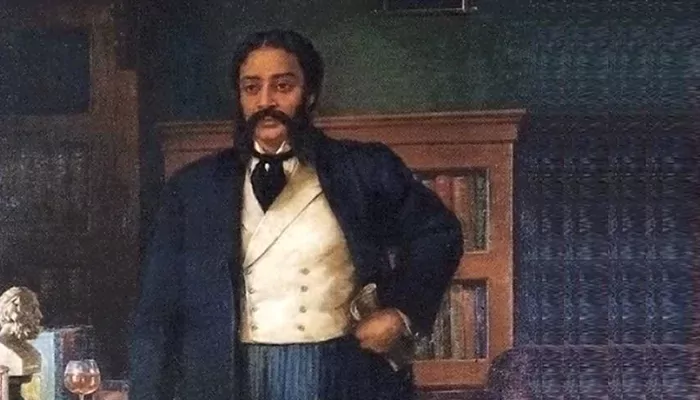

The reach of Nil Darpan grew when Reverend James Long, an Irish missionary sympathetic to the Bengali cause, arranged for its English translation and publication. The translation, done by noted poet Michael Madhusudan Dutt, was sharp and effective.

But this act came at a cost. In 1861, Long was tried for libel and fined Rs. 1,000. He also spent time in jail. The fine was paid by Kaliprasanna Singha, a philanthropist and patron of the arts.

The trial didn’t bury the play—it amplified it. The courtroom became a new kind of stage, and Nil Darpan was now the performance everyone was talking about.

A law to gag the curtain

The British soon realised that the theatre had become a threat. In response, they passed the Dramatic Performances Act in 1876. This law gave the government power to ban any play it found seditious, scandalous, or politically disturbing.

But Bengal’s playwrights had already discovered the power of subtext. If direct protest was banned, they used allegory. If real names were risky, they invented kingdoms and kings who resembled colonial rulers a little too closely.

The stage had become a battlefield. And playwrights were now revolutionaries with scripts instead of swords.

More than just Nil Darpan

Inspired by Mitra’s boldness, other dramatists followed suit. Gaekwar Darpan, Chakar Darpan, and many other socially charged plays emerged. They tackled caste oppression, landlord cruelty, and the politics of servitude.

These were not elite productions. They played in courtyards, school halls, and local festivals. Urban and rural audiences alike came to see stories that reflected their struggles. Theatre, once a luxury, was now a mirror—and sometimes, a weapon.

The legacy of theatrical resistance

The impact of Nil Darpan wasn’t temporary. It laid the foundation for politically conscious theatre in India. Even Rabindranath Tagore, though more philosophical in tone, was influenced by this legacy of using performance as critique.

In the 20th century, the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) carried forward the tradition with plays that addressed independence, poverty, and inequality. And all of it can be traced back to that one revolutionary moment when Bengal’s stage dared to defy the Empire.