Steam, Silver, and Strategy: How India’s First Business Tycoon Played the British at Their Game!

- Sayan Guha

- 6 months ago

- 4 minutes read

The audacious life of Bengal’s first cosmopolitan prince—industrialist, reformer, and host of India’s most decadent parties on the river

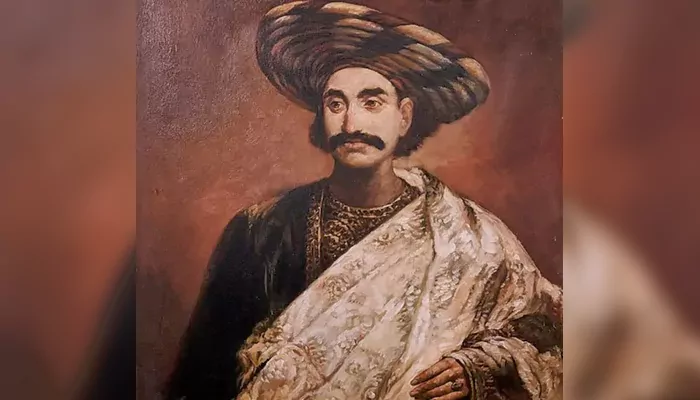

Before Rabindranath penned an anthem or redefined Indian poetry, his grandfather, Dwarkanath Tagore, was already rewriting the rules of Indian ambition. In a city poised between Mughal shadows and Victorian grandeur, Dwarkanath emerged not just as a businessman, but as a cultural impresario—a man who imported steamships and champagne in equal measure, hosting soirées on the banks of the Hooghly that blurred the lines between East and West.

To his contemporaries, he was both a riddle and a revelation. A devout Hindu who signed the anti-sati petition. A Bengali patriarch who was exiled from his own ancestral home for dining with Europeans. And above all, a visionary who believed the future of India would be built with coal, contracts, and culture.

Jorasanko: The house of quiet rebellion

Born in 1794 and adopted into the wealthy Tagore household, Dwarkanath inherited more than wealth—he inherited vision. At Jorasanko, the family's stately home, he broke caste taboos by partnering with English businessmen, founding Carr, Tagore & Co.—the first Indo-British firm of its kind. Coal, indigo, shipping, tea—he invested in the arteries of empire and built an industrial portfolio that outstripped most native merchants of the day.

But his cosmopolitan leanings came at a price. His wife, Digambari, appalled by his indulgence in meat, wine, and European company, cast him out of the family residence. Undeterred, Dwarkanath simply built another palace.

(Credit: Inmathi )

Belgachia: A pleasure palace for two worlds

Far from Jorasanko, he built Belgachia Rajbari—a neoclassical palace meant for celebration. It featured everything: marble halls, silver-pillared thrones, Venus statues emerging from lotus lakes, and lawns large enough to hide an army. This was no private home—it was a stage for influence.

Here, Dwarkanath hosted Calcutta's prominent figures, including British generals, European opera singers, Indian elites, and reformers, all of whom gathered. The waltz, the quadrille, the naach, and the fireworks followed each other with precision. Emily Eden, niece of Governor-General Lord Auckland, once remarked on his parties: "He is the only man in the country who gives pleasant parties."

It was at Belgachia that Dwarkanath achieved his most extraordinary transformation—not in business, but in creating a sense of belonging. He cultivated a delicate, performative camaraderie with the colonial elite, not through politics or rebellion, but through art, etiquette, and conspicuous consumption.

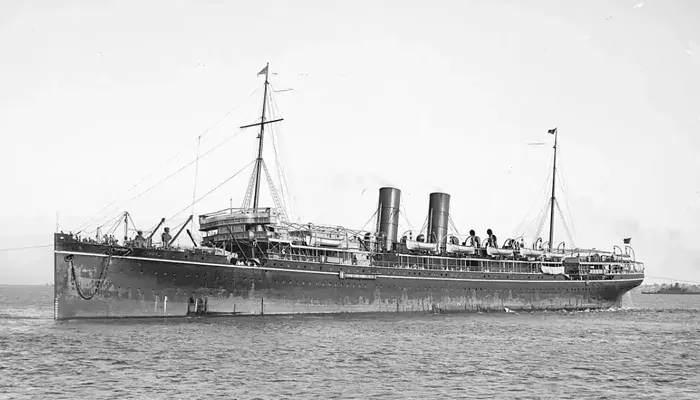

The steamer to England—and the final curtain

Ever the statesman of style, Dwarkanath travelled to England in 1842 aboard his own steamship, accompanied by a physician, three Hindu servants, and a Muslim cook. His schedule included lunches with Charles Dickens, meetings with Prime Minister Peel, and banquets hosted by Queen Victoria. He received admiration, flattery, and perhaps some fear for his worldly knowledge.

However, during his second visit in 1846, his journey ended abruptly. A sudden illness claimed him one London evening, and the man who once illuminated Calcutta with a thousand lamps was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery. His grave remains well-maintained and dignified—an ironic contrast to Belgachia, which has fallen into ruin, its gilded rooms now abandoned to the ravages of time.

(Credit: MeisterDrucke)

A legacy out of step with his time

Dwarkanath Tagore was more than just a merchant. He was a social renegade who balanced colonial power and cultural innovation. He built bridges—not only across rivers but across races, rituals, and ideologies. His vision for India was ahead of its time: modern, pluralistic, industrial, and outward-looking.

If Rabindranath Tagore gave India its poetic conscience, Dwarkanath gave it its first cosmopolitan flair. One dreamed of freedom through words. The other dared to live it—with a steamer, a string quartet, and a ballroom beside the Hooghly.