Rabindranath Tagore’s Death Anniversary: A Life That Taught Us to Live With Depth, Not Noise

- Sayan Paul

- 6 months ago

- 6 minutes read

Honoring the man who showed us that a meaningful life is full of soul.

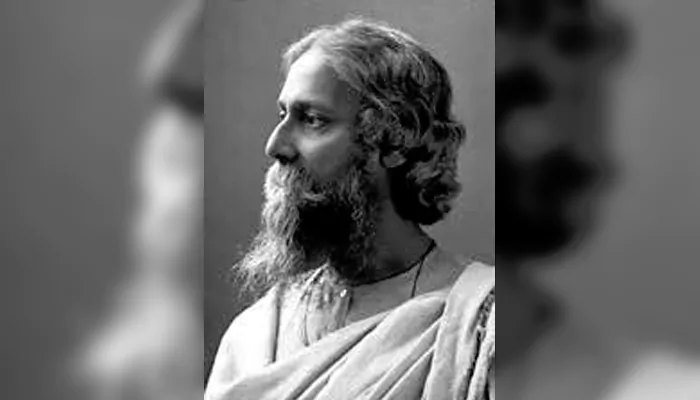

Rabindranath Tagore’s writings have taught generations how to look at life with depth and grace. But where did this understanding come from? The answer lies in his own journey. Tagore lived every shade of life. He knew love, loss, and everything in between. His life was full of emotions and experiences that shaped his worldview and, in turn, his timeless words.

As we remember him on his death anniversary, let’s look back at the vastness of his life and understand just a little more about the man behind the verses, and how his journey can guide ours.

Death Walked With Him...But So Did Joy

Tagore’s early world was filled with music and mysticism, but it didn’t shield him from sorrow. He was just a boy when his mother died. And that was only the beginning. His wife, Mrinalini Devi, died young, followed by his daughter, then his teenage son, and eventually his youngest daughter. Each loss chipped away at the certainties of life, but not at his will to live it fully.

He never turned these personal tragedies into public lament. Instead, his reflections on death were meditative. He once wrote, “Death belongs to life as birth does. The walk is in the raising of the foot as in the laying of it down.”

1890 :: Rabindranath Tagore With Daughter Madhurilata pic.twitter.com/26QmobIS75

— indianhistorypics (@IndiaHistorypic) June 20, 2021

(Credit: indianhistorypics)

His poetry (Gitanjali, Shesher Kobita, and so many songs in Gitabitan) grapples openly with mortality. But they do so without morbidity. In Gitanjali, joy flows not from blind optimism but from the understanding that beauty is heightened by life’s impermanence. And he never sentimentalized grief. He didn’t make a cult of it either. What he did was respect it, learn from it, and let it deepen him. In short, he turned pain into perspective and sorrow into something luminous.

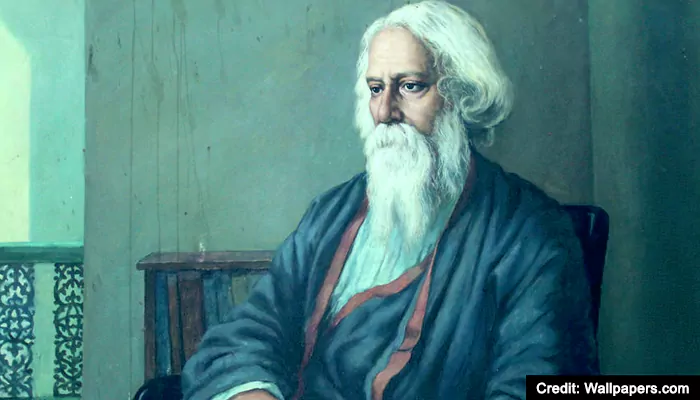

A Landed Elite Who Chose to Build From the Soil

Born into a powerful Bengali family, Tagore grew up in a mansion full of music, debate, and artistic freedom. His father, Debendranath Tagore, was a respected reformer, and the family’s wealth could have shielded Rabindranath from the harsher truths of Indian life. It didn’t.

Rather than live in isolation, Tagore stepped out to work for the masses. At Shantiniketan, he envisioned a university not bound by walls but open to wind and sky. He taught outdoors, encouraged students to explore, and rejected the idea that education should feel like punishment. “The highest education,” he wrote, “is that which makes our life in harmony with all existence.”

His short stories, novels, and essays reflect an empathy for India’s working class and rural poor. In Chokher Bali, Noukadubi, Palli Samaj, and others, he portrayed women, laborers, and village life with a realism that was neither romantic nor condescending.

Neither Loyalist Nor Loud Nationalist

If Tagore’s views on nationalism seem nuanced, it’s because they were forged in a time of turbulence and held up to the light of principle. In 1919, when British troops opened fire on a peaceful gathering in Amritsar, killing hundreds, Tagore responded not with outrage alone but with action. He renounced the knighthood he had received just four years earlier. “The time has come,” he wrote to the Viceroy, adding, “when badges of honor make our shame glaring.”

1919 :: Letter by Rabindranath Tagore to Lord Chelmsford, Returning His Knighthood in Protest Against Jalianwalla Bagh Massacre #AzaadiKiNishaniyan pic.twitter.com/LrFZgzvfmu

— indianhistorypics (@IndiaHistorypic) August 7, 2018

(Credit: indianhistorypics)

Tagore believed deeply in India’s right to self-determination. He supported the Swadeshi movement, wrote against colonial policies, and encouraged cultural confidence. But he was also among the first to caution against turning nationalism into dogma. In his 1917 essay Nationalism in India, he warned that nationalism divorced from humanity would lead only to division. “India has never had a real sense of nationalism,” he wrote, adding, “That is why she has survived all these years.”

His novels also spoke this truth. Ghare Baire (The Home and the World) explores the tensions between political idealism and personal relationships, raising questions still relevant today. Raktakarabi (Red Oleanders) allegorizes the violence of greed and unchecked authority.

He Aged, But Never Withdrew

By the 1930s, Tagore had lived through the death of most of his loved ones and a growing unease with the path India’s politics was taking. His health faltered, and yet his creative fire refused to dim. In his seventies, he began painting, and over 2,000 paintings would follow. He composed songs well into his final years, and some of his most beloved Rabindra Sangeet pieces were written when he could barely stand. He continued publishing essays on science, spirituality, and internationalism. His conversations with Albert Einstein and Romain Rolland were genuine intellectual dialogues. In 1932, he directed a film titled Natir Puja.

Albert Einstein met fellow Nobel Prize laureate Rabindranath Tagore at his home in the outskirts of Berlin #OTD in 1930. The two distinguished minds explored the concepts of science, consciousness and philosophy.

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) July 14, 2025

Read an excerpt of their conversation: https://t.co/RqDwMYzWTC pic.twitter.com/N2molFQjow

(Credit: The Nobel Prize)

Even as his body declined, he embarked on international journeys to speak about unity, peace, and the spiritual bond between East and West. He didn’t romanticize either; rather, he simply believed they needed to meet as equals. In his final years, he wrote: “The night is dark and I am far from home. But I go on.”

How Tagore Guides Us Today

Tagore doesn’t fit neatly into hashtags or campaigns in today's digital era. He doesn’t lend himself easily to the binaries of today. But that’s exactly why he matters. Nowadays, grief is often filtered through Instagram, and activism is reduced to slogans. Tagore’s life, on the other hand, is a reminder that presence matters more than performance. He lived his truths and never tried to escape. He refined his pain into something that could help others feel less alone. He insisted that silence had a voice, and depth wasn’t old-fashioned.

"The butterfly counts not months but moments, and has time enough."

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) July 24, 2025

- Rabindranath Tagore, awarded the 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature for his sensitive, fresh and beautiful poetry. He became the first non-European literature laureate. pic.twitter.com/khP08OD5tS

(Credit: The Nobel Prize)

There’s a poem Tagore wrote late in life. “Let me not pray to be sheltered from danger, but to be fearless in facing it.” That was how he lived his whole life. He was wide awake to both life’s beauty and brutality. And his life was full of contradictions: a spiritual man who embraced science, a landowner who sided with peasants, a patriot who challenged nationalism, and an artist who never stopped learning. But it was never hypocritical, but always honest.