Home Rule Movement: When Tilak and Besant Redrew India’s Political Map!

- Sayan Guha

- 6 months ago

- 4 minutes read

How the Home Rule Movement ignited India’s first united cry for self-governance

It was 1916. The world was at war, empires were collapsing, and across the British colony of India, a strange restlessness began to simmer. On the surface, the colonial machinery operated as usual—rails, tax collectors, court summons. But beneath the quiet hum of empire, a new voice started to echo: “India for Indians.”

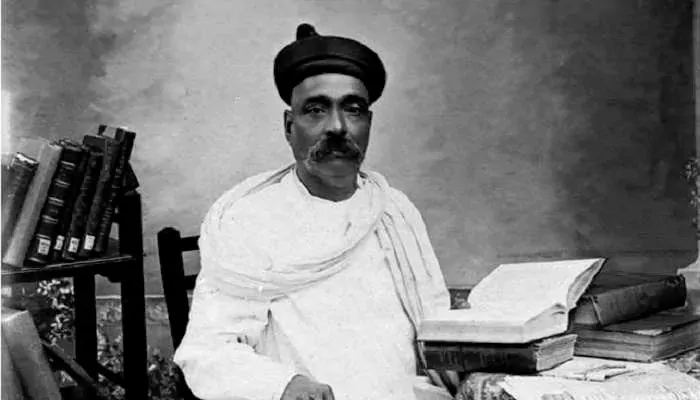

That voice came not from one, but two unlikely allies: Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a fierce nationalist returning from exile, and Annie Besant, an Irishwoman turned theosophist who believed India deserved the same autonomy Britain promised its dominions. Their movement—Home Rule—would challenge colonial arrogance and unite a fractured nationalist front.

(Credit: Wikipedia )

Why home rule, and why now?

At that time, Indian politics was in a deadlock. The Congress Party was divided between moderates and extremists. Many leaders had been jailed or silenced. Meanwhile, World War I continued, depleting India’s resources and manpower without offering any promise of reform.

The 1909 Morley-Minto Reforms had provided only symbolic representation to Indians, but it was a superficial gesture. The British still held all the control.

However, Besant saw a strategic opportunity. “England’s need is India’s opportunity,” she declared, encouraging Indians to demand Home Rule—not full independence, but autonomy within the British Empire, similar to Ireland. The moment had arrived to insist on governance by Indians as a demand, rather than a mere request.

(Credit: Cultural India )

A league of their own

In April 1916, Tilak established the first Home Rule League in Belgaum, concentrating on Maharashtra, Karnataka, and the Central Provinces. Following in September, Besant founded her league in Madras, covering the rest of India.

Together, they formed a formidable dual movement. Tilak energised crowds with passionate speeches in Marathi and Hindi heartlands. Besant, through her influential journal New India, wrote with clarity and conviction that inspired the English-speaking elite.

The leagues tirelessly recruited members, holding meetings throughout Madras, Bihar, Orissa, Gujarat, Punjab, and Sindh. In both cities and remote villages, people—particularly the educated middle class—began to envisage a political future beyond passive acceptance.

(Credit: Chegg India )

When the moderates marched too

One of the movement’s most significant achievements was its ability to reunite the divided Congress and bridge the gap between moderates and radicals. It even attracted the Muslim League, which had previously kept its distance from Hindu-majority politics.

The 1916 Lucknow Pact was a direct result of this spirit of unity. The Congress and the Muslim League, for the first time, agreed on a joint set of demands to present to the British. That cooperation laid the groundwork for a broader national movement in the years ahead.

(Credit: Fortis Edu )

Besant behind bars, a nation awakens

When Besant was arrested in 1917, British officials believed the movement would fade away. Instead, the streets erupted in protest. Her detention sparked a new wave of demonstrations, and support grew—ironically making her a national icon.

Even the usually cautious Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who would later part ways with Congress, joined the Home Rule Movement at this time. Petitions were signed by thousands, and political meetings spilt into towns that had never before echoed with slogans of swaraj.

Under mounting pressure, the British announced the Montagu Declaration on 20 August 1917, promising a “progressive realisation of responsible government in India.” Although vague, it marked the first official acknowledgement of self-governance as a policy aim.

The movement fades, but its fire lingers

By 1919, the tide was turning. Tilak sailed to London to fight a libel case; Besant, partly satisfied with the reforms, slowed her activism. Meanwhile, a new figure—Mahatma Gandhi—was emerging, with a mass-based, non-violent vision of protest that would soon overshadow elite-led politics.

In 1920, the Home Rule League merged with Congress. Gandhi took charge. But the seeds of unity, activism, and political literacy sown by the Home Rule movement would fuel the independence struggle for decades to come.