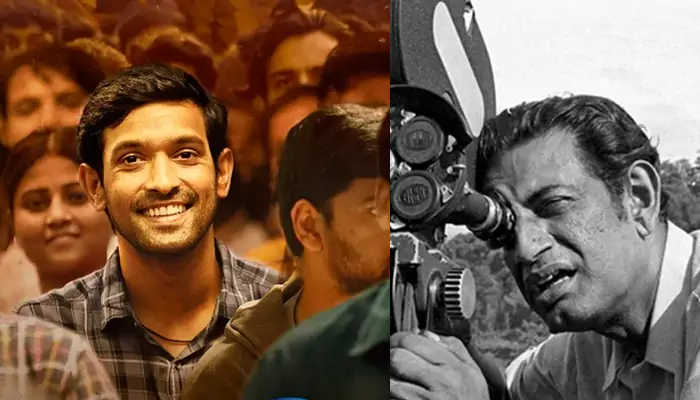

Happy Birthday, Vidhu Vinod Chopra: '12th Fail' and the Satyajit Ray School of Storytelling

- Sayan Paul

- 5 months ago

- 9 minutes read

If Ray were alive, he would have blessed Vidhu Vinod Chopra for ‘12th Fail’.

When '12th Fail' was released, cinephiles across the country (especially from Bengal) couldn’t help but notice the use of the same haunting instrument that was used in Satyajit Ray’s 'Pather Panchali'. It felt like Chopra tipping his hat to the master. However, the connection doesn’t stop there. Vidhu Vinod Chopra has long been a devoted admirer of Ray, slipping in subtle nods to him through several of his films. With '12th Fail', though, the tribute feels stronger and much more layered. Look closely, and you’ll find Ray’s influences everywhere.

So, as Chopra turns a year wiser today, let's revisit the film and understand it better.

The Courage to Never Run Away from Life, No Matter How Difficult the Journey Feels

In 'Apur Sansar', the last chapter of Satyajit Ray’s legendary Apu Trilogy, the protagonist is a young man grappling with life's uncertainties and his own place in it. Apu, a writer, introduces his character in words that sound almost autobiographical:

"A village boy. Poor but sensitive. His father's a priest. The father dies. The boy comes to the city. He doesn't want to be a priest. He'll study. He's ambitious. He studies. Through his education and struggles, we watch as he sheds his old superstitions and fixed views. He questions everything and takes nothing on trust. Yet he has imagination and sensitivity. Little things move him and bring him joy. Perhaps he has greatness in him, the ability to create, but...doesn't make it. However, it doesn't end there. It's not a tragedy. He does nothing great. He remains poor, in want. But he never turns away from life. He doesn't run away. He wants to live. He says living itself brings fulfillment and joy. He wants to live!"

The idea that "He doesn’t run away” is at the heart of Ray’s cinema. For him, the true tragedy was not failure itself, but the act of giving up. And this is exactly the spirit Vidhu Vinod Chopra channels in '12th Fail'. Manoj, a small-town boy with very little to fall back on, dares to dream of something audacious (cracking the UPSC). It’s a dream that looks really absurd from where he comes. Yet, much like Apu (and many other characters from Ray's world), he keeps walking into the storm. He fails, he breaks down, but eventually, he starts again. The film isn’t about overnight success; it’s about the art of restarting, and the courage to say, “One more try.”

(Credit: Saregama Music)

And yes, it is in that stubborn refusal to give up that Manoj finally finds victory.

When the Ordinary Becomes Extraordinary

One of Satyajit Ray’s greatest gifts was his ability to find cinema in the lives of ordinary people. Whether it was the young man in 'Pratidwandi', the clerk in 'Jana Aranya', or the housewife in 'Mahanagar', Ray showed us that the so-called “common” life was filled with uncommon meaning. His characters were everyday people who, through their struggles, revealed something extraordinary about the human spirit.

And that spirit runs through '12th Fail'. On paper, Manoj doesn’t belong anywhere near the UPSC exam. The path is thought to be reserved for the elite, especially the IIT and IIM graduates, the privileged few. Even the interviewers in the film talk about this bias. But Chopra turns this very idea on its head. Manoj, a boy written off as a “12th Fail,” dares to dream, and then to compete, and ultimately breaks into a world not meant for him. In doing so, Manoj aligns with Ray’s philosophy that ordinary lives can carry extraordinary power. It reminds us that the greatest stories are not always about people born with privilege, but about those who fight their way through impossibility.

Eyes as the Windows to the World

In 'Pather Panchali', when Apu is born, the first thing Ray shows us are his eyes, and it's through those eyes that the world unfolds. Throughout his career, Ray returned to the idea again and again that eyes can hold stories words cannot. Apu and Durga, watching the train rush past (their gaze wide with wonder), become a metaphor for life moving forward. In 'Pratidwandi', Siddhartha’s searching eyes reflect the unrest of a society in transition. Because for Ray, the eyes were a lens through which we enter both the character and the world they inhabit.

Now, Vidhu Vinod Chopra taps into the same language in '12th Fail'. Manoj’s eyes tell us as much as his words. When he looks at a police officer for the first time, there is reverence. When he meets someone who has just cleared the IPS, his stare carries both awe and determination. His journey is marked more by what his eyes register, particularly dreams, doubts, and then resilience. And just like that, the film's emotional core is built through Manoj's gaze.

Space as a Mirror of the Character

The space in Ray's films reveals who his characters are and where they stand in life. In 'Pather Panchali', the crumbling house with its leaking walls and broken courtyard tells us everything about the family’s financial situation. In 'Apur Sansar', the torn cushions in Apu’s rented room show his lack of money, but the open windows letting in air and light suggest a mind alive with ideas, and never trapped. In 'Gupi Gayen Bagha Bayen', the stark difference between the palaces of Shundi and Halla (one calm, the other chaotic) reflects the contrasting worlds of peace and war.

Chopra uses this same language in '12th Fail'. The aerial shot of Manoj’s mud house in Chambal, surrounded by barren land, instantly places him in isolation, far from the world of privilege. Later in Delhi, the tiny room he squeezes into feels suffocating, capturing his struggle to breathe in an unfamiliar, competitive city. In contrast, Shraddha’s space (more open) reflects the distance between their worlds, not only in comfort but also in opportunity. Even the exam hall becomes a stage where Manoj’s fight for space in society plays out.

Through these choices, Chopra establishes Ray’s idea that space isn’t just where a character lives but also who they are, and how the world sees them.

The Long Takes and the Ethic of Attention

For Ray, the long take was a method for making cinematic time match a character’s inner rhythm. Sustained shots let actions arrive in real time, giving actors room to reveal subtle shifts of feeling without line readings. In films such as 'Pather Panchali' and 'Charulata', Ray holds the frame through ordinary gestures and domestic routines so that meaning accumulates slowly. In 'Jalsaghar', the unbroken musical sequences turn performance into a measure of decline. In 'Mahanagar' and 'Nayak', extended framings register social pressure and personal unspooling by keeping the camera a calm witness rather than an impatient judge.

Vidhu Vinod Chopra imports this discipline into '12th Fail' with clear intent. The aerial shot of Manoj’s Chambal house is held until the landscape itself registers distance and want. In Delhi, the camera remains with him in the cramped room, observing study, fatigue, and resolve as continuous time rather than a series of edited moments. An exam-hall sequence watches his face move from panic to composure in one uninterrupted beat. And yes, the interview corridor is filmed as a corridor of pressure, not quick cuts.

Those long takes do work that montage cannot. They create endurance in the viewer, or more precisely, a shared duration that turns preparation into drama. Chopra uses duration as a moral device. By making us inhabit Manoj’s time, the film insists that persistence and aspiration deserve sustained attention. That is a lineage straight out of Ray, where patience itself becomes a form of storytelling.

Moral Compass Without Preaching

Satyajit Ray’s moral art depended on staging ethical dilemmas rather than resolving them for the viewer. In 'Mahanagar', the question of a woman working is explored through small shifts in domestic routine, the redistribution of chores, and the recalibration of authority. 'Jana Aranya' exposes the corrosive logic of a marketplace by tracing incremental compromises, each choice generating its own consequence. 'Pratidwandi' presents political disillusion as a series of encounters that erode certainties, and not as a manifesto. Now, what unites all these films is a trust in consequence, and consequence alone, to make the moral point.

'12th Fail' makes institutional bias explicit through dialogue when interviewers mark pedigree over merit, but it does not resolve the question with a speech. Instead, moral meaning accrues through how Manoj inhabits challenges. An extended exam sequence converts anxiety into ethical pressure; the corridor outside the interview room functions as a testing ground where composure and humility speak louder than arguments. Manoj’s repeated returns to study after each setback, his refusal to take shortcuts, and the way he steadies himself before an interviewer are ethical acts rendered as habit. These gestures accumulate into moral identity.

What is striking is the film’s refusal to separate individual virtue from structural reality. Chopra invites the audience to judge by watching and to feel the weight of systems on embodied action. The effect is a moral pedagogy that mirrors Ray’s.

Satyajit Ray gave generations of filmmakers a grammar of compassion. '12th Fail' stands as another example that this grammar still breathes, finding new urgency in the story of a young man from Chambal who refuses to let circumstances dictate his destiny. We could go on drawing lines between Ray and Chopra, but perhaps it is enough to say that films like '12th Fail' reassure us that the inheritance of Indian cinema is alive, evolving, and still capable of moving us.

And yes, Happy Birthday, VVC!