Sculpting with Yak Butter: The Insane Artistry Behind Losar's Colourful Altars

- Devyani

- 3 weeks ago

- 3 minutes read

Forget marble and bronze; in the high Himalayas, the most sacred masterpieces are carved from grease and ice.

I’ve often wondered why we humans insist on making things difficult for ourselves. We build cathedrals out of heavy stone and paint ceilings while dangling from scaffolding. But nothing quite matches the beautiful, slightly masochistic dedication of a monk elbow-deep in a bucket of ice water, trying to prevent a lump of yak butter from melting between his palms.

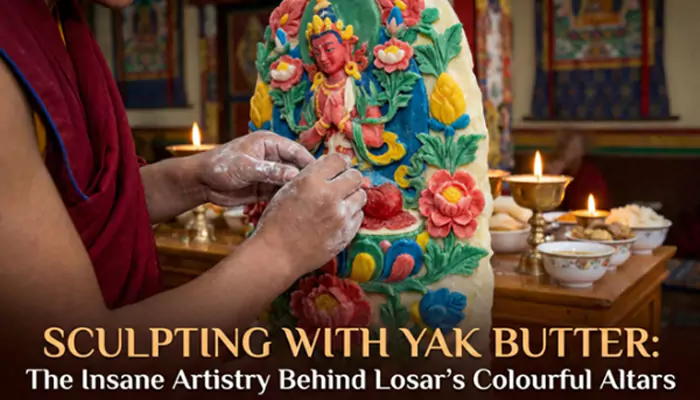

Welcome to the World of Tormas

As Losar - the Tibetan New Year - approaches, the monasteries of Ladakh, Tibet, and Bhutan transform into frantic, freezing workshops. This isn't your standard Sunday morning "sculpting class." This is a grueling test of endurance where the medium is as temperamental as a toddler and twice as slippery.

Why Butter, Though?

It seems an odd choice, doesn't it? If you want to create a sacred offering, why choose something that turns into a puddle the moment the sun hits it?

Actually, that is exactly the point. In Himalayan Buddhism, the transience of the art is the lesson itself. You spend weeks - sometimes months - crafting these psychedelic, neon-colored towers of intricate flowers and deities, only to watch them be dismantled or cast into a river once the festival ends. It’s a vivid, greasy reminder that nothing stays put. Not the butter, and certainly not us.

To get that vibrant, "breaking the internet" look, monks mix the butter with mineral pigments. We're talking shocking pinks, electric blues, and deep turquoises. The result is something that looks less like a religious icon and more like a high-end prop from a Wes Anderson movie set in the clouds.

The Physics of Chilled Grease

The process is, frankly, a nightmare. To work with butter, you have to keep it firm. This means the monks work in unheated rooms during the dead of winter. To keep their own body heat from ruining the fine details - the petals of a lotus or the curve of a dragon’s scale - they must constantly dip their hands into freezing water.

I can barely handle a cold shower in February. These guys are doing it for hours on end, their fingers turning a ghostly blue just to ensure a yak-butter goddess has a perfectly straight nose. It’s a level of "doing it for the craft" that makes most modern artists look a bit lazy, perhaps?

A Modern Lens on an Ancient Greasiness

Today, as we scroll through our sleek, digital lives, there’s something grounding about the smell of yak butter. It’s heavy, slightly rancid, and utterly human. While the world outside debates the latest tech trends, the monasteries are quiet, save for the scraping of butter and the low chant of prayers.

It’s not just "art." It’s a physical manifestation of patience.

When the altars are finally unveiled on the 15th day of the New Year - the Butter Lamp Festival - the glow of thousands of lamps reflects off these waxy masterpieces. It is, quite literally, a flickering moment of perfection. Then, it’s gone. And honestly? That’s the best part.