How a song of devotion turned into a battle cry—and sparked controversy across colonial and communal lines

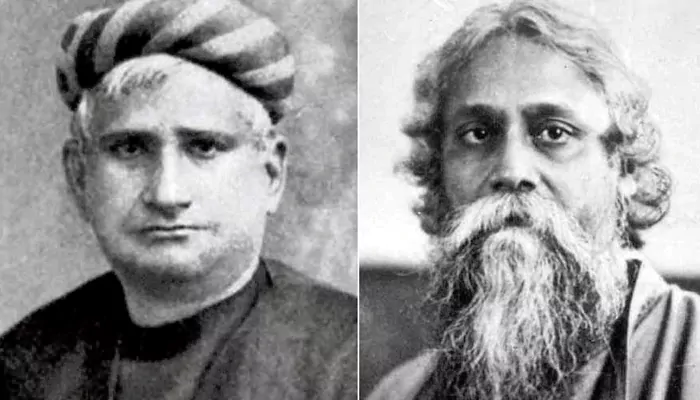

When Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay wrote Vande Mataram in the 1870s, he probably never imagined it would one day shake the foundations of an empire. Set against the backdrop of colonial Bengal, the poem praised the land as a divine mother. What began as verse in a novel soon became a symbol of resistance. But by the early 1900s, the British saw it as a threat. Some Indian leaders, too, especially in a society as diverse as India's, hesitated. The national song stood on the edge of censorship and controversy.

Vande Mataram first appeared in Anandamath, Bankim's 1882 novel about Hindu monks rebelling against a Muslim ruler. The novel was fictional, but the sentiment was sharp. The song's early verses praised the beauty of the land—its rivers, grains, and green fields. But later verses invoked Durga, the Hindu goddess of power.

Rabindranath Tagore was among the first to set it to music. In 1896, at the Indian National Congress session in Calcutta, he sang it aloud. It was an emotional moment. The song's future as a nationalist anthem was sealed.

During the Swadeshi Movement in 1905, when Lord Curzon partitioned Bengal, Vande Mataram became the voice of protest. It was sung in processions, printed on pamphlets, and shouted from street corners. British officials grew uneasy. To them, it wasn't just poetry—it was political fire. In many provinces, the colonial administration banned the public recitation under sedition laws. Printing presses that carried it were raided. Activists who sang it were jailed.

The British feared what the song had come to represent—a mass awakening.

Not all resistance came from colonial rulers. By the 1910s, several Muslim leaders began to voice their discomfort. The association of the "Mother" in the song with Durga—a Hindu deity—was seen as religiously exclusive. The fact that Anandamath portrayed Muslims as historical enemies added to the unease.

Prominent Muslim figures, including those in the Muslim League, questioned whether the song could unify the nation. They argued it alienated non-Hindu Indians, particularly with its religious overtones in the later stanzas.

The issue resurfaced in 1937, when the Congress came to power in several provinces under the Government of India Act. Schools and public institutions began incorporating the national anthem, "Vande Mataram," into their daily routines. But protests followed. The Congress Working Committee had to step in.

After discussions involving leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru, Subhas Chandra Bose, Maulana Azad, and Rabindranath Tagore, a middle path was chosen. Only the first two stanzas—those that spoke of the land, not the goddess—would be sung officially. The rest could be left aside to respect India's religious diversity.

Interestingly, even as Congress tried to defuse communal tensions, the British stuck to their restrictions. In several instances, Vande Mataram remained barred from public broadcasts and events. The colonial state feared any mass expression of unity. It was only after independence that the ban was lifted for good.

On January 24, 1950, the Constituent Assembly adopted "Vande Mataram" as the national song, granting it equal status to the national anthem, "Jana Gana Mana." But the compromise from 1937 still stood—only the first two stanzas were deemed fit for official use.

The journey of Vande Mataram reflects India's complex and multifaceted relationship with nationalism and pluralism. It was never just a song—it was a slogan, a symbol, and sometimes, a source of division. However, it also reminded Indians of their shared heritage, their everyday struggles, and their shared hopes.

Even today, the echoes of early 20th-century debates are still audible. Yet, Vande Mataram endures—not because it was perfect, but because it carried the spirit of a people in motion.