During the mid-18th century, the Marathas invaded Bengal repeatedly, causing widespread destruction and loss.

There’s no point in holding grudges against a particular community for what happened centuries ago. We don’t go around hating the British today just because they once colonized us and exploited our people. In the same way, the hate-mongering we see in some recent Bollywood films (I’m sure you have guessed which ones) makes little sense. It has never been about one community versus another; it has always been about power. Now, the Maratha raids in Bengal are a brutal chapter in our history that doesn’t get much attention today, and there won't be any 'The Bengal Files' based on it, simply because it doesn’t fit the current trend of targeting a particular religion. The Marathas repeatedly invaded Bengal in the mid-18th century, but does that mean all Marathas should be hated by the Bengalis today for what their ancestors did? Of course not. Hate built on history is meaningless, as it only blinds us to the real story.

If you want to know how Bengal faced wave after wave of Maratha invasions, and why “Bargi elo deshe” (the Bargis came to the land) still comes to our memory, read on. Again, this is only about history.

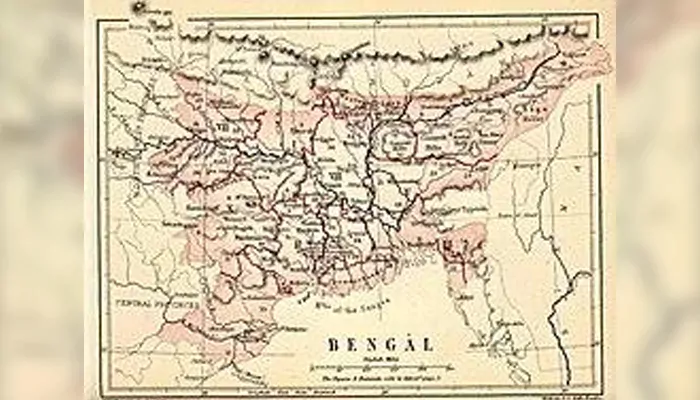

By the 1740s, Bengal was a glittering province of the Mughal empire, though the empire itself was fading fast. Nawab Alivardi Khan, who seized power in 1740, presided over a territory that stretched across Bengal, Bihar, and parts of Orissa. Its silk, textiles, and most importantly, fertile fields made it one of Asia’s wealthiest regions.

But the Mughal centre could no longer hold. Regional nawabs asserted autonomy, and external enemies circled. To the west, the Marathas had grown from a confederacy of warrior clans forged by Shivaji into an expansive force under the Peshwas. Among them, the Bhonsles of Nagpur under Raghuji Bhonsle looked eastward.

Now, the word “Bargi” comes from the Marathi bargir, cavalrymen equipped and maintained by the state. Swift and lightly armed, they were designed for speed and surprise. But for Bengal, this mobility was devastating.

Bengal’s wealth made it irresistible. The Marathas, who funded their wars through tribute called chauth (a quarter of a province’s revenue), wanted Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa under their fold.

Politics within Bengal added fuel to this. When Alivardi Khan toppled Nawab Sarfaraz Khan in 1740, Sarfaraz’s allies sought Maratha support. Mir Habib, once in Alivardi’s service, defected and became the invaders’ guide.

Nawab Alivardi Khan of Bengal with his grandson & heir apparent Siraj-ud-Daulah meeting the nobles of Murshidabad. pic.twitter.com/hkcjLfcrWm

— Timurid-Mughal Archives (@Timurid_Mughal) July 6, 2023

(Credit: Timurid-Mughal Archives)

Historians stress that the motive was revenue, not religion. The silk trade routes through Orissa, the fertile plains of Bengal, and the weakening of Mughal control, all these made the province a prize. Local rivalries and internal rebellions made the Maratha advance easier.

The Bargi raids stretched roughly from 1741 to 1751, unfolding in waves.

1741-42: The First Assault. Raghuji Bhonsle sent Bhaskar Ram Kolhatkar with 40,000 cavalry. They ravaged Orissa, swept into Bengal, and plundered Hooghly and Murshidabad. Alivardi fought back at Burdwan, but could not stop the looting.

1743-45: Treachery and Escalation. Pathan officers rebelled against Alivardi. In 1744, he lured Bhaskar Ram to Katwa under the guise of parley and had him killed. Raghuji, enraged, took command himself.

1746-48: The Height of Devastation. Raghuji’s son Janoji led fresh raids. Battles like Ranisarai in 1748 saw Bengal’s elephants crush Maratha cavalry, yet every dry season brought fresh incursions into Bihar and western Bengal.

1749-51: Stalemate and Exhaustion. The raids lost intensity as Alivardi’s relentless pursuit wore down the attackers.

Through it all, Alivardi Khan proved both ruthless and resilient, defending his province against superior numbers with cunning and stamina.

The Marathas relied on mobility. Bargis on fast horses descended without warning, looted, burned, and vanished before defenders could even gather. They struck in dry months, avoiding floods and rivers swollen with monsoon rains.

Alivardi turned Bengal’s geography into his ally. He fortified towns, organized peasant militias, and used riverboats as floating defenses. His elephants, deployed with precision, shattered cavalry formations, most famously at Ranisarai. He also knew when to purge disloyal generals and when to bargain with defectors.

The toll was staggering, to say the least. Contemporary Dutch accounts suggest 400,000 people died in Bengal and Bihar during the decade of raids. Villages burned and crops withered, while merchants and weavers vanished. Silk looms fell silent, mulberry groves dried up, and fields lay fallow. Revenue collapsed, and migration reshaped Bengal’s demography.

What survives most vividly is the lullaby that came from it. "Chhele ghumalo, paada judaalo, borgi elo deshe…" Mothers hushed their children with the terror of marauders, weaving famine and fear into the rhythms of daily life. It is folklore as a historical record.

By March 1751, both sides were drained. The treaty at Katwa ceded Orissa up to the Subarnarekha River to the Marathas. Bengal agreed to pay an annual tribute of 1.2 million rupees. Mir Habib was installed as governor of Orissa, though his assassination in 1752 confirmed Maratha dominance.

For Bengal, it meant respite but also loss. Alivardi died in 1756, leaving a weakened province. And the Marathas held Orissa until the British swept it away in 1803.

Later retellings cast the Bargi raids as a religious war, a Hindu revenge on a Muslim nawab. In reality, Bengal’s Hindus bore the heaviest suffering, and it was Alivardi (Turkic-Afghan by origin) who defended them. Poets like Gangaram in his Maharashtra Purana recast events with sectarian zeal, but historians expose these as propaganda. Temples, too, were plundered, a reminder that revenue, not piety, drove the raids.

Today, the same myths are recycled online, feeding divisions. Yet history resists such simplification. The Bargis came for money, not faith, and their raids devastated communities across lines of religion.

The Marathas and Alivardi Khan fought for wealth and survival, and ordinary people carried the burden. To miscast such events as communal struggles is to misunderstand the past and endanger the present. And the lullaby should remind us that civilians always pay the highest price, and empathy (not blame) is the only inheritance worth carrying forward.