Amid temples and fortresses, traders from every shore found a haven in the Vijayanagar Empire. This is the story of how a medieval Indian city opened its gates and rewrote the rules of commerce

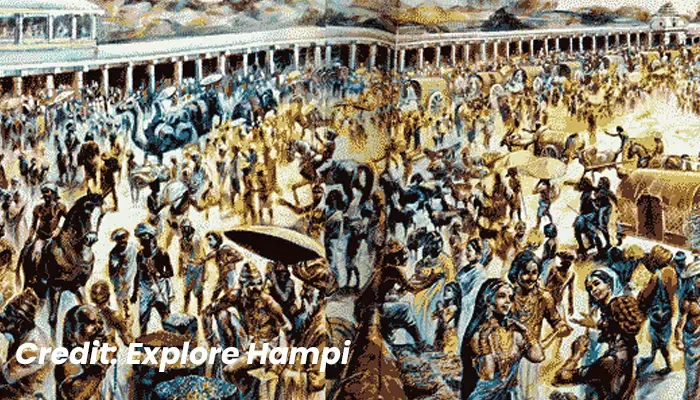

Before the world had heard of Wall Street or the Silk Road became a standard term, Hampi—capital of the Vijayanagar Empire—was already teeming with brokers, bargaining merchants, and caravans laden with stories and spices. Situated along the Tungabhadra River and adorned with magnificent architecture, this city was not merely a temple town; it was a global marketplace cloaked in medieval splendour.

Founded by the brothers Harihara and Bukka in the 14th century, Vijayanagar rose like a giant in southern India. Its rulers understood something many empires overlooked: trade is power, and prosperity follows commerce like a shadow.

With commerce ingrained in its very fabric, Hampi became a stage where traders from Persia, Arabia, China, Southeast Asia, and Europe played their roles. Pepper, cardamom, ginger, and tamarind were weighed by the fistful. Precious stones, musk, silk, and seed-pearls shimmered under the marketplace sun.

From sturdy pack-bullocks and head-load carriers called Kavadis to river vessels capable of carrying men and oxen alike, goods moved across land, water, and sheer human effort. According to Portuguese traveller Duarte Barbosa, even buffaloes and ponies joined the relay of transport.

Trade wasn't just about goods—it was about grit.

The sea did not divide, rather it connected. Vijayanagar's western ports, such as Mangalore, Honnavar, and Calicut, and its eastern gateways, including Pulicat and Nagapatnam, became vital nodes in global trade networks. Arab dhows, Chinese junks, and Portuguese caravels—all dropped anchor here. According to Persian traveller Abdur Razzak, the empire boasted over 300 ports, each buzzing with life and filled with commerce.

Imports were equally exotic—coral, vermilion, coloured velvets, rosewater, and quicksilver arrived ashore. Saffron from Persia, camphor from Burma, and porcelain from China flowed in, illustrating that Hampi was less a city and more a confluence of civilisations.

Every ledger entry represented a guild. The Pekkandru, Virabanajigas, Nakaramu, and Paradesi weren't merely names; they were institutions that managed wealth, settled disputes, protected traders, and maintained product standards.

The Virabanajigas, known as the "Valiant Merchants," left their influence across Karnataka, Andhra, and Tamil regions. Meanwhile, the Paradesis, true to their label, included foreign merchants like Portuguese, Arabs, and early Dutch traders.

Even skilled artisans, such as potters (Kumbhalikas), weavers (Padmasale), and oil-pressers (Tilaghatakas), formed guilds, illustrating that Vijayanagar's economy was grounded both at the top and in local communities.

The empire's coinage was as sophisticated as its cities. Gold, silver, and copper coins—Varaha, Gadyana, Hon, Jital—were minted with standard weights and denominations. For the common folk, barter still thrived.

Yet, the financial system was so strong that even taxes like Mula Visam and Mulavisabadi were calculated with accuracy and fairness. Trade wasn't just encouraged—it was protected, nurtured, and institutionalised.

Travellers like Niccolò de' Conti, Afanasy Nikitin, and Domingo Paes were captivated. They left behind tales of wealth, irrigation-based agriculture, bustling streets, and courtyards filled with silks and sandalwood. Their accounts revealed an empire that thrived on both order and opulence.

Even as wars raged and thrones changed hands, the kings of Vijayanagar—the Rayas—never abandoned trade. They lowered taxes during famines, provided shelter to foreign merchants, and kept their ports open while many other empires shut theirs.

In today's hyper-connected world, where trade deals and treaties dominate headlines, the story of Vijayanagar serves as a reminder: true prosperity lies not just in hoarding wealth but in opening doors.

And Hampi? She opened them wide, and the world walked in.