The untold story of schoolgirls who turned lunchboxes into weapons of revolt

In 1930s British India, rebellion wore many disguises. But no one expected it to wear a school uniform and carry a tiffin box. In the lanes of Bengal, amid rising nationalist fervour, teenage girls quietly trained to fight. They didn't shout slogans on the streets. They passed their exams by day and planned assassinations by night. And often, their weapons of choice were smuggled past British police — neatly hidden between parathas and boiled eggs.

As the British tightened control following the Non-Cooperation and Civil Disobedience movements, a new wave of revolution brewed in Bengal. While male revolutionaries dominated headlines, a quieter but equally determined resistance was taking shape in girls' schools. Organisations like the Chhatri Sangha (Women's Students' Association) and Jugantar welcomed young women into their fold. Here, they were trained in physical combat, firearms, and covert communication.

Many of these girls came from educated, middle-class families. They had read Bankim and Tagore. They understood nationalism, and more importantly, they believed in sacrifice. Their age gave them cover. So did their innocence. And they used it brilliantly.

The tiffin box was never questioned. It was routine — part of every schoolgirl's day. British officers and guards, who frisked young men for pamphlets and pistols, never thought to inspect a girl's lunch. This assumption was fatal.

Wrapped inside a clean napkin, nestled next to homemade food, revolvers were transported across cities. Girls used the boxes to carry messages, bullets, even cyanide capsules. What seemed like lunch breaks were missions. The lines between student and soldier blurred.

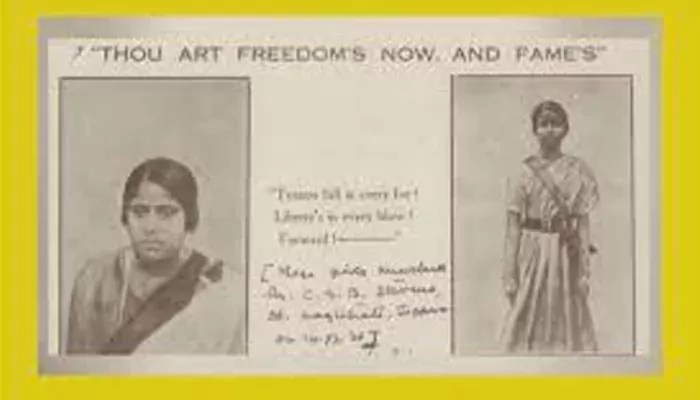

The most famous instance of this daring tactic came in 1931. Two schoolgirls from Comilla, Santi Ghose (15) and Suniti Chowdhury (14), were active members of Jugantar. On December 14, they walked into the office of British magistrate Charles Geoffrey Buckland Stevens under the pretext of delivering a petition.

Their schoolbags and tiffin carriers had hidden a small revolver. As Stevens stood up to receive them, they shot him dead. The girls were arrested immediately. Their act shook the Empire. Two teenagers had just executed a top colonial officer, and they showed no remorse. Instead, they said they were proud.

Schools, particularly in Calcutta and Comilla, became centres of quiet resistance. Many headmistresses sympathised with the cause and looked the other way. Others unknowingly fostered revolutionaries by encouraging reading, critical thought, and discussion. Subjects like history became weapons. Girls read about Rani Lakshmibai, then practised firing pistols in secret courtyards.

Study hours were often interrupted by strategy sessions. Science notebooks hid diagrams of bombs. Even the playground became a place to rehearse escape routes. These young girls balanced algebra with anarchy.

The British clamped down. Many schoolgirls were arrested, detained without trial, or sent to remote prisons. Yet, they endured. Suniti and Santi were given lengthy sentences. Inside jail, they wrote poetry, mentored other prisoners, and refused to apologise. Their resolve inspired others, not just women, but every Indian who felt voiceless.

The crackdown led to tighter surveillance in schools. Teachers were questioned. Tiffin boxes were now checked. But by then, the message was clear — rebellion was no longer limited to guns and marches. It lived in whispers, books, and lunch boxes.

Today, these girls remain forgotten, mainly in mainstream retellings of the freedom struggle. Their names may not appear in textbooks, but their spirit lives on in every young person who speaks truth to power. They showed that courage isn't about size or strength. Sometimes, it's about walking into danger with a smile, a ribbon in your hair, and a pistol in your tiffin.

These were not just students. They were warriors in disguise.

And history, though slow to remember them, can never erase what they did.