Chhota Nagpur’s Kols rose against colonial corruption and land grabs

In the winter of 1831, a revolt swept through the thick forests of Chhota Nagpur. It did not begin in royal courts or among the educated elite. It started with the Kols—tribal communities who had lived for generations in harmony with the land. When that land was seized by force, they rose.

The Kol Uprising was one of the first major rebellions against British rule in eastern India. It wasn’t just an outburst of anger. It was a direct response to broken systems, foreign laws, and the betrayal of age-old tribal customs. Forgotten by many, this uprising holds a crucial place in the early resistance to colonialism.

The British East India Company had extended its influence into the Chhota Nagpur plateau by the early 19th century. Their arrival brought dramatic changes. The traditional system of tribal self-governance and communal land ownership was quickly dismantled. In its place came revenue collectors, moneylenders, and landlords—mostly outsiders who didn’t understand or respect tribal customs.

The Kols, Oraons, Mundas, and other indigenous groups were pushed out of their lands. New settlers claimed their fields. Debt began to pile up. Corruption became rampant. The tribal way of life was no longer protected. The balance had been broken, and resistance began to brew.

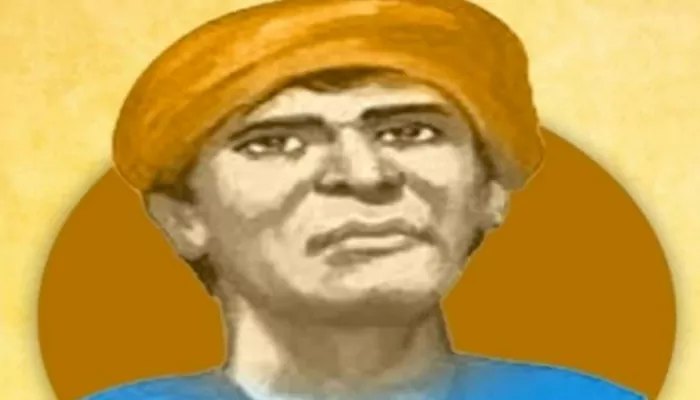

At the heart of the rebellion stood Budhu Bhagat, a leader of the Oraon tribe. Born in what is today Jharkhand, Bhagat was a respected figure in his village, known for his courage and clear vision. When oppression turned unbearable, he became the face of revolt.

He united various tribal groups under one banner. The aim was simple: to drive out the exploiters and reclaim their forests. With bows, arrows, axes, and spears, the rebels attacked British outposts and targeted landlords who had seized tribal lands. For a short time, they succeeded in taking control of several parts of Ranchi, Palamu, Gumla, and Hazaribagh.

The British administration, caught by surprise, quickly realised the scale of the uprising. Reinforcements were rushed in. Martial law was declared in many parts of the region. What followed was a brutal crackdown.

Budhu Bhagat and his two sons were eventually surrounded near Silagai village. In a fierce encounter, both his sons were killed. Bhagat too was shot, refusing to surrender. He died fighting—an image that would forever remain etched in the memory of his people.

Even after the leadership was crushed, it took months for the British to regain control. The dense forests had become a battleground.

What led to such a massive and organised uprising? The answer lies in land and identity. Tribal communities had their unwritten laws and rights. But the British introduced systems of private ownership, tenancy, and taxation that did not fit tribal realities.

Outsiders who obtained land through colonial rule became landlords. They forced the tribes into bonded labour or turned them into tenants on their ancestral land. Combined with rising debt, insults to their traditions, and unchecked exploitation, the Kols had reached a breaking point.

Though the Kol Uprising was ultimately suppressed, it left a lasting impact. It was among the first coordinated tribal movements against colonial rule. It proved that forest communities, despite lacking formal training or modern arms, could mount a powerful resistance.

In modern-day Jharkhand, Budhu Bhagat is still remembered. Schools, roads, and memorials bear his name. His story is passed down in folk songs and oral traditions. The uprising also laid the groundwork for future tribal movements like the Santhal Rebellion of 1855 and Birsa Munda’s Ulgulan in the 1890s.