From a fearless teenager in Kakinada to a lawyer, parliamentarian, and nation-builder, Durgabai’s life was a masterclass in civic courage

Durgabai Deshmukh was barely twelve when she challenged the gendered silence of colonial India. Born in 1909 in Rajahmundry, Andhra Pradesh, she grew up watching her father tend to the sick during deadly outbreaks of plague and cholera—lessons that instilled in her a profound sense of service. By 1921, she had already made her presence felt.

When Mahatma Gandhi visited Kakinada, young Durgabai demanded that he address a gathering exclusively for devadasis and veiled Muslim women—groups long ignored in public discourse. Organisers dismissed her request unless she raised ₹5,000, an impossible sum for a child. She did it in a week. Gandhi not only kept his promise but asked the spirited girl to translate his speeches during his Andhra tour.

This was the crucible of the Non-Cooperation Movement, and Durgabai's defiance set the tone for a lifetime of public action.

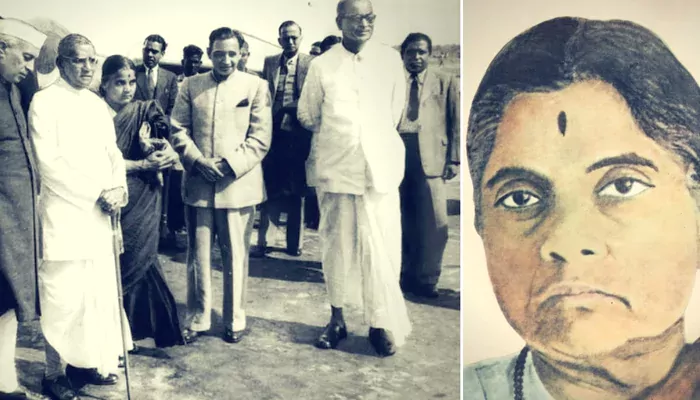

(Credit: Outlook India )

In an era when child marriage was common, Durgabai's moral compass remained steadfast. Married at eight, she left her marital home as a teenager, convinced of the injustice of the practice. Her family, unusually progressive for the time, supported her decision.

In 1923, she was already trusted enough by the Indian National Congress to oversee the Khadi exhibition at its Kakinada session. She famously refused Jawaharlal Nehru entry without a ticket, earning his respect for her unwavering fairness.

By 1930, she was a key organiser of the women's wing during Gandhi's Salt Satyagraha, an act that resulted in her arrest. She spent nearly three years in prison, where she realised how many women inmates did not even understand the charges against them. This realisation sharpened her sense of justice: she resolved to study law and provide free legal aid.

Denied a hostel at Andhra University, she advertised in newspapers, rallied other aspiring women students, and founded one herself. She earned degrees in Political Science and Law from Madras University, quickly becoming a respected criminal lawyer.

Durgabai's vision reached far beyond courtrooms. In 1937, she established the Andhra Mahila Sabha, a women's welfare organisation that still operates schools, hospitals, and vocational centres across South India.

Her work attracted the attention of the Congress leadership, and in 1946, she was appointed to the Constituent Assembly, one of only fifteen women among the 389 members who drafted independent India's Constitution. She proposed over 750 amendments, advocated for women's property rights, and championed judicial independence.

As the only woman on India's Planning Commission in 1950, she laid the foundation for a national social welfare policy and promoted the establishment of Family Courts. Her advocacy influenced women's education policy as chair of the National Council on Women's Education, securing free primary education for girls and supporting adult literacy programmes.

(Credit: The Better India )

After marrying Chintaman Deshmukh, India's first Indian Governor of the Reserve Bank and later Finance Minister, Durgabai continued her work with unwavering zeal. She represented India at the United Nations, the World Food Congress, and UNESCO, which later honoured her for her literacy initiatives. The Government of India awarded her the Padma Vibhushan in 1975.

Durgabai Deshmukh died in 1981, but the institutions she founded—such as the Andhra Mahila Sabha and the Durgabai Deshmukh Centre for Women's Studies—continue to uplift communities across India. She remains a towering yet under-recognised figure, a woman who marched with salt and fire, and built the scaffolding of a fairer nation.