How the philosopher-president imagined a world where religion and governance worked together for justice and peace

Imagine a world where politics respects faith without exploiting it, and religion unites rather than divides communities. Such a vision might sound utopian in today's fractured times, yet it was central to the life and philosophy of Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan.

Born on September 5, 1888, the teacher-turned-statesman dedicated his intellectual and political career to bridging two spheres often seen in conflict—religion versus politics. His dream was neither a theocracy, where religion dominates politics, nor a soulless state stripped of values, but a society guided by universal spiritual values while remaining politically secular and just.

For Radhakrishnan, religion was not about rituals or rigid dogmas, but about humanity's eternal quest for truth. He drew deeply from Vedanta, seeing all religions as different pathways leading to the same summit. To him, exclusivism was a betrayal of religion's essence; pluralism was its most authentic expression.

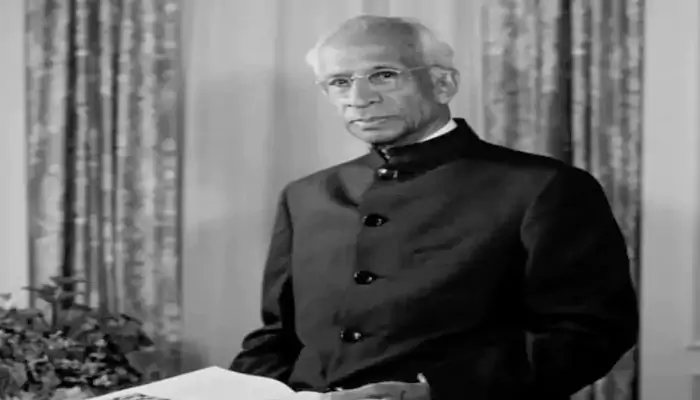

Credit: India Today

He frequently invoked the Vedic maxim, “Truth is one, the wise call it by many names,” as the cornerstone of his outlook. This recognition of diversity was not mere tolerance—it was the celebration of multiple ways of seeking the divine.

Building on this vision, Radhakrishnan proposed the idea of a “universal religion.” This was not a new sect or creed, but a philosophical framework that distilled the essence of every faith—love, compassion, humility, and justice.

Such a universal religion, he believed, could unite humanity beyond sectarian boundaries, enabling us to see shared values rather than differences. In a world scarred by communal strife, his humanistic approach stands out as a blueprint for peaceful coexistence.

Even as he honoured spirituality, Radhakrishnan insisted that the political sphere remain secular. His secularism was not a denial of religion, but rather its equal respect. For him, India’s strength lay in its pluralism, and the state’s role was to ensure that no faith dominated others.

This was not merely a political calculation but a moral necessity—to protect the dignity of every citizen and to foster a just society where freedom and equality could thrive.

Paradoxically, while he separated institutional religion from politics, he did not exclude spirituality from public life. For Radhakrishnan, governance was more than administration; it was the integration of spiritual ideals—like justice, compassion, and non-violence—within the secular framework of politics. In his view, the presence of spirituality in politics uplifted it beyond mere power struggles.

In his view, democracy was not just a system of votes but a moral order that enabled individuals to realise their potential within a larger collective good.

Radhakrishnan’s tenure as Vice-President and later as the second President of India exemplified this synthesis. As ambassador to the Soviet Union, he relied on reason and dignity to strengthen ties in a tense Cold War environment.

Credit: The Hindu

As President, he acted less as a partisan figure and more as a moral compass, reminding the young republic of its duty to uphold pluralism, justice, and education. His insistence that his birthday be celebrated as Teachers' Day reflected his conviction that educators, more than politicians, shape the nation's soul.

Today, the world Radhakrishnan envisioned feels fragile. Rising religious nationalism, sectarian politics, and intolerance threaten the pluralist ideals he supported. Critics often dismiss secularism as alien to India's traditions, yet Radhakrishnan’s vision was deeply rooted in its philosophical heritage—one that embraced diversity, not division.

His reminder that the state must remain impartial while individuals draw on their faith for moral strength remains as urgent today as it was in the turbulent years after independence.