It wasn't really about winning a match. For Mohun Bagan, it was about reclaiming pride and standing up to colonial rule.

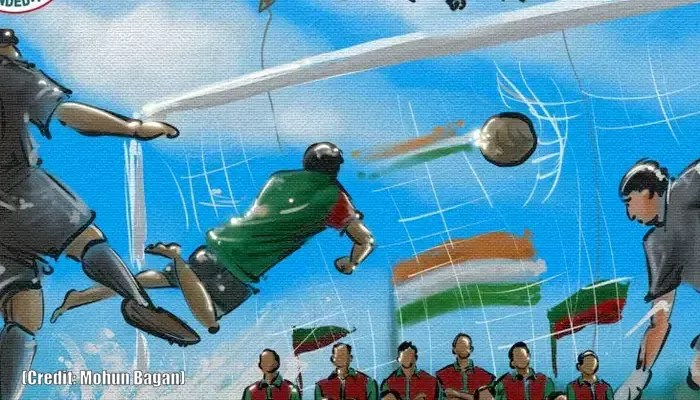

If you remember 'Lagaan' (of course you do), you’ll know the match was never really about cricket. It was about pride. It was a battle for dignity, where Bhuvan and his team faced off British officers for what was theirs. They knew nothing about cricket, learned it from scratch, and turned the game into a symbol of defiance. However, while 'Lagaan' was fiction, something eerily similar played out in real life, back in 1911, in Calcutta. Only this time, the game was football. And the heroes were eleven young men from Mohun Bagan. Eleven barefoot Indians took on a British team in boots, on their own turf. Back then, wearing shoes wasn’t common for Indian players, but that didn’t stop them. Against all odds, the Indian team defeated the British, and that single win totally sent ripples across the country. It showed the British that Indians could not only stand up to them but also defeat them at their own game.

So, as we gear up to celebrate India’s 79th Independence Day, let’s look back at that day when a simple football match turned into a statement of the freedom movement.

Mohun Bagan had been around since 1889. By 1911, it had become one of the better-known clubs in Calcutta, not because it had won much, but because it represented something more personal to many Indians. In a city that was still the capital of British India, the idea of a local team going up against the colonizers felt powerful, even if it was just on a football pitch.

At the time, Bengal was already simmering. The partition of the province in 1905 had angered people across communities, leading to the rise of the Swadeshi movement (a push to reject foreign goods and reclaim Indian identity). Football, like many things in that era, became much more than what it seemed on the surface. British teams played in boots, had better training, and had access to better facilities. Indian teams, on the other hand, were often underprepared and underfunded.

Shoes cost money. A good pair could cost Rs 7, as much as a schoolteacher’s salary back then. So naturally, most Indian players played without them. But over time, it became a symbol of resistance. Playing barefoot became a statement: we don’t need to copy you to beat you.

The Mohun Bagan team that played that day is still remembered as the "Immortal Eleven." But back then, they were just a group of young men comprising students, clerks, and others.

Their captain, Shibdas Bhaduri, was 24 and knew how to rally his team. Alongside him were players like Hiralal Mukherjee in goal, Sudhir Chatterjee, the only one to wear boots, and Abhilash Ghosh, who would go on to score the winning goal. Many of them came from small towns and villages, particularly from what is now Bangladesh.

They trained under Sailen Basu, a no-nonsense man and a Subedar Major in the British Army. He didn’t pamper them; rather, he believed in them and made sure they were focused and ready for the tournament.

Their decision to play barefoot wasn’t only about not having money. On dry grounds, playing without boots gave them an edge, but it was also risky. On wet ground, like in the previous year’s semi-final, they slipped and were knocked out. Luckily for them, July 1911 was dry. And they were ready.

To reach the final, Mohun Bagan had to go through a series of tough matches, mostly against British teams. They beat St. Xavier’s College 3–0, edged past Rangers 2–1, squeezed past the Rifle Brigade 1–0, and finally took down the Middlesex Regiment in a replay after drawing the first game.

As their winning streak grew, so did the buzz. People from Bengal, Bihar, and Assam made their way to Calcutta. Special trains were arranged. Steamers crossed the Hooghly, packed with fans. Tickets that cost Rs 1 or Rs 2 were being resold for Rs 15 on the black market, an enormous sum for the time.

On match day, the Calcutta Football Ground was literally overflowing. Some say there were 60,000 people. Others claim it was closer to 20,000. Either way, the place was packed with thousands more perched on trees, rooftops, even telegraph poles, trying to catch a glimpse. Kites flew above the ground to signal scores to those outside.

At 5:30 PM, the game kicked off. The East Yorkshire Regiment looked sharp and confident. Within 15 minutes, they scored a free kick from Sergeant Jackson. The crowd fell silent, but Mohun Bagan didn’t back down. In the second half, Shibdas Bhaduri equalized, and the roar that followed was really deafening. Just two minutes before the final whistle, Abhilash Ghosh collected a loose ball and found the net.

Mohun Bagan had done the unthinkable. Crowds stormed the field. People sang, danced, cried, and whatnot. Cries of “Vande Mataram” rang out across the Maidan. Hindus and Muslims joined hands in victory processions. Diyas were lit at homes. Some said it felt like Diwali had arrived early. As The Times of India wrote the next day, “Every Bengalee carried his head high… the rout of the King’s soldiers in boots and shoes by barefooted Bengalee lads.”

See, it wasn’t about winning a trophy. Simply put, it was a punch to colonial arrogance. For decades, British teams had ruled the football scene, and Mohun Bagan’s win was a crack in that wall.

Even The Englishman newspaper, a British publication, admitted: “Mohun Bagan has succeeded in what the Congress and the Swadeshiwallas have failed to do: to explode the myth that the Britishers are unbeatable.” Historian Boria Majumdar later wrote, “Mohun Bagan had become synonymous with the national battle cry for Vande Mataram.”

Of course, the players didn’t set out to make a political statement. Sailen Basu was still a British Army officer. The club’s top brass wasn’t part of the freedom struggle. But the public saw it differently.

The story of July 29, 1911, still resonates. In 2011, a Bengali film called 'Egaro' (Eleven) brought it to the big screen. Although it wasn’t a box-office hit, the film made waves among football lovers. Writers like Novy Kapadia (Barefoot to Boots) and Jaydeep Basu (Stories from Indian Football) have written in detail about the match and its impact. Even back in 1911, poet Karunanidhan Bandhopadhyay had written a song calling the players “desher chele” - sons of the nation.

And every year, Mohun Bagan celebrates July 29 as "Mohun Bagan Day." The club gives out its highest honor (the Mohun Bagan Ratna) on this day. In 2010, India Post issued a stamp to mark the historic win, and in 2017, when FIFA launched ticket sales for the U-17 World Cup, they did it at 19:11 IST, paying a tribute to that legendary year.

Most importantly, Mohun Bagan’s win laid the foundation for Kolkata’s deep-rooted football culture.