Agrarian fury, religious strife, and anti-colonial rage exploded in the Malabar region

In the late summer of 1921, the tranquil coastal belt of Malabar — with its swaying palms and red-tiled homes — erupted into one of the fiercest uprisings against British rule in southern India. The Moplah Rebellion, also known as the Malabar Rebellion, was not just a local disturbance. It was a storm of pent-up frustration. British administrators, unprepared for the scale of the violence, found themselves at the heart of a rural revolt driven by a complex web of social, religious, and political grievances.

The Moplahs (or Mappilas) were a Muslim agrarian community descended partly from Arab traders who had settled on Kerala’s coast centuries earlier. By the 20th century, most Moplahs in Malabar were tenants or small farmers living under the oppressive thumb of Hindu landlords — known as jenmis — in a land tenure system bolstered by colonial authority. For decades, they endured high rents, forced evictions, and a justice system that favoured the elite. Beneath the surface of daily life, anger simmered.

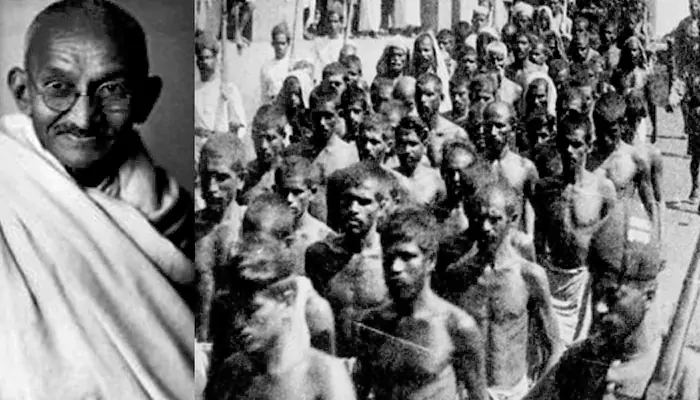

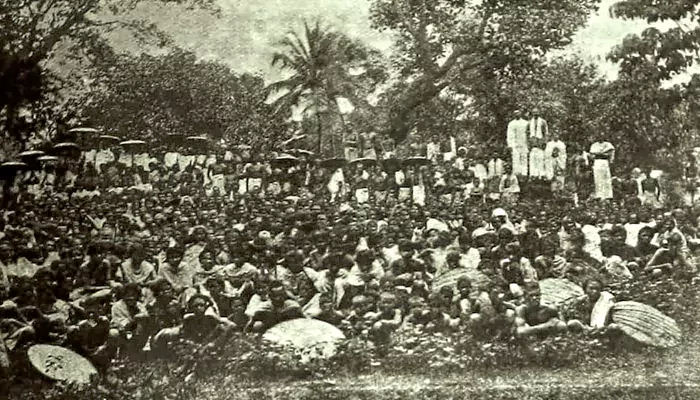

The immediate backdrop of the rebellion was the national Khilafat and Non-Cooperation movements. The Khilafat agitation, which sought to defend the Caliphate after World War I, found support in Malabar, especially among Muslims. Meanwhile, Gandhi’s call for non-violent resistance against the British was gaining traction. Local leaders held meetings, boycotted British institutions, and mobilised peasants. In Malabar, this charged atmosphere took a different turn. What began as a peaceful protest soon spiralled into an armed revolt.

On August 20, 1921, British police raided a mosque at Tirurangadi, suspecting it to be a rebel hideout. The Moplahs reacted with fury. What followed was a chain of attacks on police stations, courts, government offices, and symbols of colonial power. The uprising spread rapidly across Eranad and Valluvanad taluks. In some areas, rebels declared independence from the British and hoisted their own flags. One leader, Variyankunnath Kunjahammed Haji, even set up parallel governance — collecting taxes, issuing passes, and running courts.

Although initially aimed at the British and the landlord system, the rebellion soon took a darker turn. Reports emerged of violent attacks on Hindu landlords and suspected collaborators. Temples were damaged, and forced conversions were alleged. This shift alarmed both British officials and Indian nationalists. Gandhi, while condemning British repression, also criticised the violence against civilians. The rebellion had transformed from a political and agrarian protest into a communal and chaotic conflict.

The colonial government responded with overwhelming force. Troops were rushed in from nearby provinces. Villages suspected of aiding rebels were burned. Thousands were arrested, tortured, or executed without trial. One of the most horrific episodes came in November 1921 — the Wagon Tragedy. Nearly 100 detained rebels were packed into a closed goods train wagon. By the time it reached its destination, 67 had suffocated to death.

By early 1922, the rebellion was crushed. Over 10,000 people were killed or displaced. Entire villages were left in ruins.

The Moplah Rebellion remains one of the most debated events of India’s colonial history. Was it a peasant revolt against feudal oppression? A communal flare-up? Or an early cry of freedom from rural India? Historians offer different interpretations. But one thing is clear: it exposed the fragility of British control in the countryside and the volatility that simmered beneath colonial peace.

In modern Kerala, memories of the rebellion are still raw. For some, it marks a bold, if bloody, stand against empire. For others, it’s a chapter of communal violence and tragedy.

What cannot be forgotten is this: in 1921, the British were shaken not by armies, but by angry peasants and barefoot rebels in the heart of Malabar.