Indulgent Feasts of Mamluk Dynasty's Teen King Revealed in Amir Khusrau's Poetry

Delhi's Turbulent Medieval Epoch and the Flamboyant Reign of Muiz-ud-din Kaiqubad

During the late medieval period, Delhi witnessed centuries of incessant turmoil. Dynasties rose and fell, with some rulers barely leaving a mark in history. One such figure was Muiz-ud-din Kaiqubad from the Mamluk Dynasty. Ascending the throne as a mere teenager, Kaiqubad swiftly compensated for his restrained upbringing by indulging fervently in both wine and women. According to a court poet, he was immersed in perpetual pleasure parties, surrounded only by moon-faced maidens with rosy lips. His voracious appetite extended beyond his pursuits to his zest for food, leaving a memorable yet tumultuous legacy in Delhi's history.

Amir Khusrau's Culinary Chronicles: A Glimpse into 13th-Century India

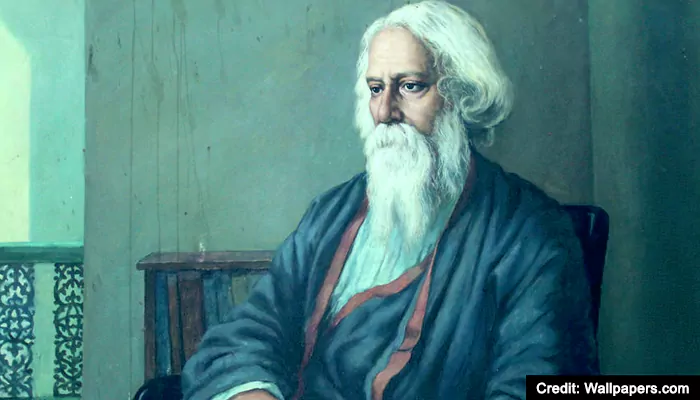

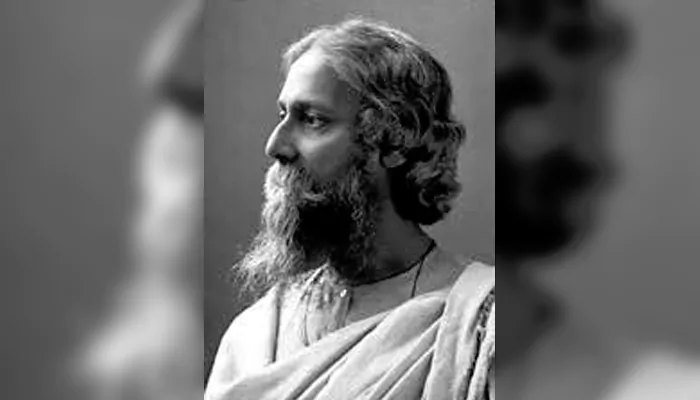

In the 13th-century text Qiran-us-Sa'dain, Amir Khusrau paints a vivid picture of opulent feasts hosted by the sultan. He depicts a grand spectacle of over 1,000 dishes presented on sturdy tripod trays, accompanied by numerous cups of sweet vegetable juice described as "tasteful and nourishing as the water of life." To cater to those seeking respite from indulgent liquor, a rose-flavored julab, consisting of water and sugar, was readily available. Amir Khusrau, acclaimed as the father of qawwali, the alleged inventor of the sitar, and one of India's eminent Persian-language poets, offers a treasure trove of insights into the culinary and cultural facets of 13th and 14th century India through his literary works, including divans, prose, and historical poems. His writings provide intriguing glimpses into the society and gastronomic customs of the era.

In his analysis of Amir Khusrau as a Historian, Professor Syed Hasan Askari underscores the profound role of historians in shedding new and enlightening perspectives on the past. He contends that Amir Khusrau's extensive body of work, brimming with substantial, factual insights, qualifies him as a historian. By virtue of his contributions, Amir Khusrau significantly enhances our understanding of history and merits recognition as a historian in his own right. Askari's perspective underscores the importance of expanding historical knowledge through fresh insights and the diligent pursuit of historical truth.

Culinary Tapestry of the Delhi Sultanate: From Royal Feasts to Exotic Imports

In his literary works, Khusrau vividly portrays the opulent feasts and extravagant culinary offerings that graced the royal kitchens of Delhi's sultans. For instance, under the reign of Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq, the kitchen staff would lay out a staggering array of over 200 dishes daily, catering to the appetites of approximately 20,000 people.Khusrau's writings reveal the profound influence of Western and Central Asian cuisines on the culinary landscape of the Delhi Sultanate. One dish he mentions is "tutmaj," akin to the Turkish "tutmac," a noodle-and-yoghurt soup believed to have originated during the time of Alexander the Great. This dish, described by Mahmud al-Kashgari as a "well-known food of the Turks," traversed borders, making appearances in anecdotes related to the Seljuk Turks, the Delhi sultans, and medieval cookery books in Chinese, Urdu, and Arabic.

Another Turkish import, "halwai-i-sabuni," finds mention in Khusrau's writings as a confection reserved for grand feasts and celebrations. Literally translating to "saponaceous pudding," this treat is detailed in Friedrich Unger's cookbook as a mixture of cooked starch, honey, blanched almonds, and sesame oil.

Khusrau also introduces us to "bughra," a dish with intriguing historical roots. Originally a simple meat dumpling attributed to the 10th-century Turkic ruler Satuq Bughra Khan, it transformed into a Persian creation consisting of flour paste strips. Abu Fazl's Ain-i-Akbari documents a bughra prepared with meat, flour, ghee, chickpeas, sugar candy, root vegetables, fenugreek, ginger, and an assortment of spices.

Beyond these, Khusrau's writings unveil a tapestry of culinary delights, including the Arabic "lauzinaj" (an almond confection), sherbets, "shikanjaben" (a sweet and sour lime-based beverage), meat-filled "samosas," "Barra-i-Birryan" (roasted goat ribs atop fragrant polaw), and "abgoosht" (a hearty Iranian meat stew). These gastronomic treasures offer a tantalizing glimpse into the rich and diverse culinary heritage of the Delhi Sultanate.

Feasting and Festivities in Medieval India: Culinary Delights and Traditions

Bread also holds a special place in Khusrau's writings, with a particular focus on two types of naan. The first, known as naan-e-tanuk, is described as a delicate, almost translucent bread, so thin that one could see through it. The second variety, naan-i-tanuri, is thicker and prepared in a clay tandoor, puffing up like a joyful dome, honored to be among royal dishes. Khusrau even suggests that naan-e-tanuk would be fitting as a cloth for Jesus's table, while naan-i-tanuri would put the humble k'ak bread to shame.Khusrau's admiration extends to mangoes, which he praises with eloquence. In a vivid tribute to the fruit, he writes:

“Naghzaki-ma (Var Khwash) naghz-kunbistan, Naghza tarin mewa (Var na mat) - Hindustan.

Our fairling (i.e. mango) beauty-maker of the garden, Fairest fruit of Hindustan, Ere ripe, other fruits to cut we bon, But mango serves us ripe or not.”

In Nur Siphir's writings from 1318, he holds mangoes and bananas in high esteem, drawing parallels between them and the grapes and guavas of Khurasan. He extols the mangoes of Devagiri, describing them as akin to "golden shells of milk and honey that, when savoured, inundate the palate with the sweetness of candied water." India's musk melon is celebrated as a fruit of paradise, with its bananas and betel leaves unrivaled anywhere. He lauds the exquisite flavor of pomegranates from Jodhpur, asserting that "few dried fruits could rival" India's cardamom and cloves.

Khusrau's writings offer a glimpse into the customs of his era, particularly during Eid festivities. During Ramzan, he recounts how people would break their fast with zalibay-i-nabat, believed to be akin to present-day jalebi, and fuqqa, a barley-based beverage infused with sugar, raisins, herbs, and spices. On Eid, the new moon signaled the end of fasting, prompting gatherings and celebrations. On this occasion, the young and children adorned themselves in fine linen and silk attire. Perfumes and rosewater were distributed using gidabdaran vessels. Gifting and sharing sweet delicacies were customary. During Shesh-i-Id, ruqaq and shakkar paich, a sweetmeat made from rice or wheat and sugar, were relished, and fine bread and sweet halwa were exchanged as gifts. Khusrau also mentions the sacrificial offerings of sheep and goats on another occasion.

These historical accounts paint a vivid picture of the culinary and cultural richness of the time, offering a glimpse into the traditions and flavors that shaped the festivities and daily life during that era.

Khusrau's Paan Passion and Regal Association

Khusrau's writings consistently reveal his fascination with tambul, or betel leaf, which he extols as a "marvelous accompaniment of food." In Nur Siphir, he asserts, "Common people have no taste in it," reserving its enjoyment for nobility and their heirs. Its elaborate preparation, he insists, is an exclusive privilege, reserved solely for the king, who symbolizes celestial alignment.Khusrau's profound affection for paan finds poetic expression, evident in one enigmatic verse:

Gala katey, woh choon na kare, aur muh rakt bahay, So pyaari baatein karein, fikar katha dikhlaye.

Throat slit, he doesn't make a sound/ Blood drips from his mouth/ He tells tales like a child/ And makes the imagination go wild.

But nothing compares to his ode to the paan in Qiran-us-Sa'dain:

“A chew of betel bound into a hundred leaves, came to hand like a hundred-petaled flower. Rare leaf, like a flower in a garden, Hindustan's most beautiful delicacy, sharp as a rearing stallion's ear, sharp in both shape and taste, its sharpness a tool to cut roots, as the Prophet's words tell us. Full of veins with no trace of blood. yet from its veins blood races out. wondrous plant, for placed in the mouth, blood comes from its body like a living thing.”