Born in the sawmills and shipyards of North America, the Ghadar Movement weaponised exile, transforming weary immigrants into revolutionaries bent on burning down the British Empire

In the early 1900s, ships from British India transported thousands of Punjabi farmers and soldiers across the Pacific to North America. They arrived seeking fair wages, stability, and dignity. However, they faced racial hostility, exploitative labour, and colonial oversight. Yet, in the alleys of Vancouver and the fields of California, a remarkable transformation occurred—anger evolved into determination. From temples and tearooms, a new movement emerged. Its name: Ghadar—meaning “mutiny” in Urdu.

What started as a murmur of dissent among farmworkers and students quickly grew into one of the earliest international efforts to fight for India’s independence. The Ghadar Movement was more than just a political group; it was a bold statement that exile would not silence their voices.

(Credit: r kondala )

Between 1903 and 1913, approximately 10,000 South Asians—primarily Punjabi Sikhs and former servicemen—immigrated to North America. Many worked in the timber mills and railway yards of the Pacific Northwest, while some pursued studies at universities such as Berkeley. Despite their contributions, they faced constant denial of political rights and were marginalised as second-class citizens. Canada’s continuous journey law and America’s racist immigration policies fueled growing frustration.

In these communities, nationalist ideals merged with socialist ideas. In gurdwaras and union halls, a new resolve took shape: if petitions could not secure India’s independence, then armed struggle was the path to liberation.

(Credit: Cafe Dissensus Everyday )

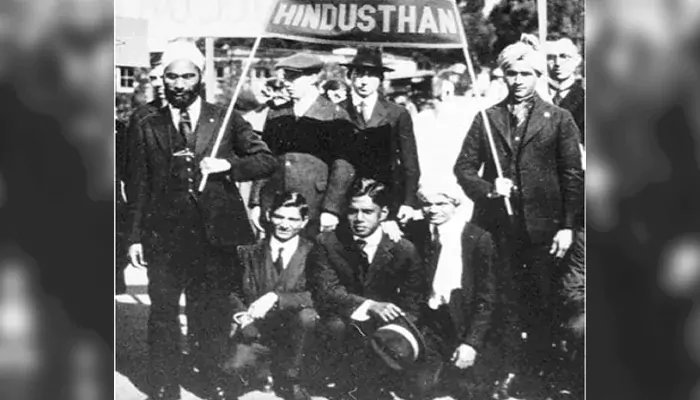

On July 15, 1913, the Pacific Coast Hindustan Association—later known as the Ghadar Party—was officially founded in Astoria, Oregon. Soon after, it moved to Stockton, California, where the local gurdwara became its key hub. Another branch established its headquarters in Oakland.

The party’s revolutionary newspaper, Hindustan Ghadar, published passionate editorials in Urdu, Punjabi, and Hindi, urging Indian soldiers to rebel against their British officers. Distributed covertly via merchant ships and secret couriers, the publication sparked hope and defiance across Punjab, with words like rebellion, freedom, and sacrifice sparking local enthusiasm.

Its early leaders included inspiring revolutionaries such as Har Dayal, Maulvi Barkatullah, Kartar Singh Sarabha, and Vishnu Ganesh Pingle—students and exiles committed to socialism, secularism, and armed resistance, with a shared dream of liberation.

When World War I erupted in 1914, the Ghadar Party saw an opening. Britain was weakened, and the global landscape was changing rapidly. Ghadar members teamed up with Germany and the Ottoman Empire in what became known as the Hindu–German Conspiracy. Their aim: to incite mutiny within the British Indian Army and ignite an armed rebellion in India.

Hundreds of Ghadar supporters returned to Punjab with weapons, money, and revolutionary writings. They planned to work with Indian revolutionaries like Rashbehari Bose and Sachin Sanyal to trigger a nationwide revolt.

However, their plans were uncovered. British spies acted swiftly and crushed the effort, resulting in the notorious Lahore Conspiracy Case. Forty-two revolutionaries faced execution. Others were jailed or forced to go into hiding.

(Credit: Kashmir Times)

Although the armed uprising did not succeed, the spirit of the Ghadar Movement persisted. It infused Indian nationalism with a militant spirit and brought the cause to an international stage long before independence. Many Ghadarites, including Udham Singh and Bhagat Singh’s ideological circle, would later influence the revolutionary phase of India’s fight for freedom.

In the years following the war, the party split along ideological lines—some members adopting Marxism, others leaning toward socialism. By 1948, it had officially disbanded. Yet, its daring experiment—transforming workers into fighters and exile into action—remains one of the most courageous chapters in India’s struggle for independence.