Long before others worldwide, Aurangzeb's son tried his hand at a Taj on a frugal scale.

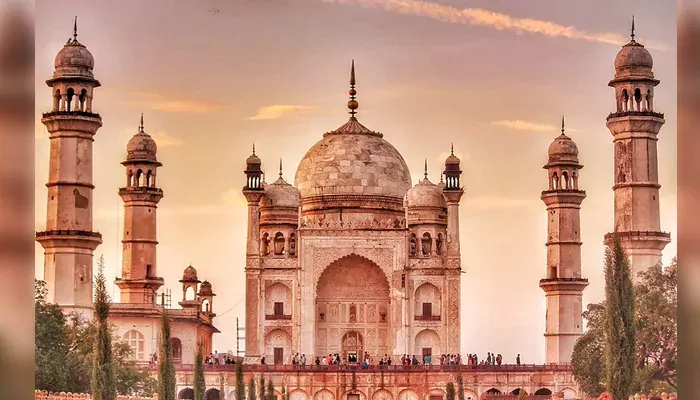

There are countless replicas of the Taj Mahal scattered across the world, yet, as it goes without saying, none of them come close to matching its splendour. Most were built knowing they could never outshine Shah Jahan’s marble masterpiece. The British, however, gave it a shot with Kolkata’s Victoria Memorial, which is grand in its own right, but still no Taj. However, the first to take on that impossible challenge wasn’t a foreign ruler at all. It was Shah Jahan’s own grandson, Azam Shah, who became the seventh Mughal emperor from 14 March to 20 June 1707. In the late 17th century, when he was a prince, he set out to build a mausoleum for his beloved mother, Dilras Banu Begum, in Aurangabad. And the result was Bibi Ka Maqbara, which is striking from a distance, but, as history remembers, a far humbler cousin of the Taj.

Bibi Ka Maqbara, commissioned by Prince Azam Shah between 1668 and 1669, commemorates Dilras Banu Begum, Aurangzeb’s first wife and Shah's mother. Often called the "Taj of the Deccan," it attempts to channel the spirit of its illustrious predecessor, paying tribute to maternal love and imperial legacy. But why did Azam Shah undertake such a project under the vigilant eye of his father? How did the changing tides of empire shape its creation? And why does it remain a shadow beside the Taj’s blazing glory? The answers lie in a story that involves everything from devotion to financial restraint, and the twilight of Mughal splendor.

The Mughal Empire’s architectural legacy comes from Persian refinement and Islamic artistry, along with Indian craftsmanship. From Akbar’s bold urban experiments like Fatehpur Sikri to Shah Jahan’s crowning masterpiece, the Taj Mahal, the dynasty’s monuments symbolized not only power, but also ideals of beauty and cultural synthesis. Shah Jahan’s reign, from 1628 to 1658, reached an architectural pinnacle. The Taj Mahal, constructed over two decades at an eye-watering cost of around 32 million rupees (billions in today’s terms), was a monument born from grief and love after Mumtaz Mahal’s death in childbirth in 1631. The project employed thousands of artisans, imported pristine marble from Makrana, and dazzled with inlaid semi-precious stones, epitomizing the empire’s vast wealth and artistic mastery.

When Aurangzeb took the throne in 1658, the empire entered a new chapter. He secured power through ruthless succession wars, imprisoning his father and eliminating rivals. His reign was marked by austerity, strict religious orthodoxy, and relentless military campaigns to extend Mughal control into the turbulent Deccan plateau. Although he expanded the empire to its greatest territorial reach, the costs were immense thanks to strained resources and heavy taxation.

In the midst of all this, Aurangzeb’s marriage to Dilras Banu Begum in 1637 linked him to Persian Safavid royalty. She became his favorite wife, bearing five children, including Azam Shah, but died tragically young in 1657 due to childbirth complications. And her death left Aurangzeb deeply bereaved.

Azam Shah, then viceroy of the Deccan, took on the task of commemorating his mother’s memory through the construction of Bibi Ka Maqbara. Aurangzeb sanctioned a modest budget of about 700,000 rupees, mere fractions compared to the Taj Mahal’s lavish spending. Designed by Ata-ullah Rashidi, son of the Taj’s chief architect Ustad Ahmad Lahauri, and supervised by Hanspat Rai, the mausoleum stood as a balancing act between filial affection and imperial frugality. Historian Abraham Eraly notes that Dilras remained “Aurangzeb’s great love,” her tomb a reminder of private sorrow amid public duty. Situated in Aurangabad, the Deccan’s Mughal capital, the mausoleum also proclaimed the empire’s authority over a region rife with rebellion.

17th century Mughal Prince Azam Shah, son of Emperor of India Aurangzeb @DalrympleWill http://t.co/jPfSzryqnF pic.twitter.com/L8tbgyh436

— Razvi (@razvinama) March 26, 2015

(Credit: Razvi)

At a glance, Bibi Ka Maqbara evokes the Taj Mahal’s iconic form: a central dome flanked by four minarets, set within a charbagh garden meticulously divided by waterways and fountains designed to reflect the paradise imagery of Islamic cosmology. Both monuments follow the Mughal hasht bihisht, or “eight paradises,” plan, embodying a sacred geometric order.

Yet, the differences become clear in the details. The Taj Mahal rests on an octagonal base, creating a dynamic, multi-angled experience for visitors; Bibi Ka Maqbara sits on a simpler square platform, lending it a more static presence. The Taj’s central dome soars to 73 meters with a pronounced bulbous curve, surrounded by four chhatris, while the Maqbara’s dome is slimmer and just 54 meters high, with a vertical elegance that feels more restrained. Its minarets are shorter, stubbier, and integrated into the platform corners, contrasting with the Taj’s detached, slender towers.

Taj Mahal by Ustad-Ahmad Lahori

— Architectural Art (A-A) (@4AAAAart) August 7, 2025

Agra, India 🇮🇳 pic.twitter.com/iSwo7BLt2A

(Credit: Architectural Art (A-A)

Materially, the contrast is immensely striking. The Taj Mahal gleams entirely in Makrana marble, alive with intricate pietra dura inlays of jasper, lapis lazuli, and other precious stones. Bibi Ka Maqbara, meanwhile, uses marble only up to about three meters from the base; above that, dark basalt stone coated in lime plaster attempts to mimic marble’s shimmer, a cost-saving compromise that has weathered unevenly. The ornamentation also reflects this frugality: where the Taj bursts with Quranic calligraphy and dazzling floral motifs, the Maqbara relies on stucco carvings and modest inlays.

Bibi Ka Maqbara - a 'Dakkhani Taj' (Taj of the Deccan) of India :

— Archaeo - Histories (@archeohistories) November 20, 2023

A a late Mughal Tomb, located in Aurangabad (now Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar), Maharashtra, India.

Bibi-Ka-Maqbara (tomb of a lady), a beautiful mausoleum of Rabia-ul-Daurani alias Dilras Banu Begum, the wife of… pic.twitter.com/4IJdpB6wEp

(Credit: Archaeo - Histories)

The scale differs markedly as well. The Taj spans 17 hectares with a vast 300-meter-square plinth; the Maqbara covers roughly 12 hectares, its enclosure rectangular rather than square. Both use symbolic numerology, with the number eight recurring in the Maqbara’s octagonal screens and minaret bases, a nod to paradise and its grand model. Yet, as architectural historian Ebba Koch observes, the Maqbara feels “half the size” of the Taj, with compressed proportions and details that lack the finesse of the original. Its garden, while laid out in the charbagh style, eschews expansive reflecting pools for narrower axial water channels, imparting a less dramatic effect.

Aurangzeb’s bond with Dilras Banu Begum was deeply personal. As a Safavid princess, she not only carried noble lineage but also bore him his heirs. Contemporary accounts describe her as his favored consort, and her death at the age of 35 struck a blow. Building a tomb in her honor mirrored Shah Jahan’s tribute to Mumtaz Mahal, though here the initiative came from their son Azam Shah, navigating the constraints of his father’s puritanical reign.

Politically, the monument served a dual purpose. The Deccan region was volatile, marked by ongoing resistance from Maratha leaders and regional sultans. Aurangabad, renamed from Khirki, became a strategic center, and Bibi Ka Maqbara functioned as a tangible assertion of Mughal permanence in the south.

Yet Aurangzeb’s strict religious orthodoxy and frugal governance limited the scope of architectural ambition. Initial requests for lavish materials were reportedly curtailed, confining the budget to a fraction of what the Taj had commanded decades earlier. Historian Surendra Sahai notes that Aurangzeb prioritized military campaigns and fiscal discipline over monumental extravagance. The mausoleum thus stands as a compromise, an effort to memorialize and consolidate legacy amid tightening imperial purse strings.

The affectionate nicknames, such as “Poor Man’s Taj" or “humble cousin,” reflect the Maqbara’s compromised grandeur. Its materials betray its modest means: lime plaster over basalt is vulnerable to weathering, dulling the building’s once-intended radiance. In contrast to the Taj’s pristine marble, this surface requires constant upkeep.

Its smaller footprint and compressed proportions dilute the visual impact. Rather than inspiring awe, it often invites comparison and, sometimes, disappointment. Decorative flourishes are restrained, lacking the Taj’s lavish pietra dura and flowing calligraphic bands. Instead, stucco and simpler carvings dominate, reducing the depth and intricacy that define its illustrious predecessor.

Bibi ka Maqbara (Tomb of the Lady)

— IIHC (مركز التراث الهندي الإسلامي) (@IndoIslamicHC) February 1, 2024

Commissioned by Azam Shah, son of Aurangzeb, in memory of her mother, Rabia ud Durrani, posthumously.Located in Aurangabad (Maharashtra), IndiaConstructed between 1668 and 69Cost: 700,000 rupeesEngineer: Hanspat RaiDesigned and erected by… pic.twitter.com/PNvgqeYnGZ

(Credit: IIHC)

Underlying these shortcomings is Aurangzeb’s fiscal conservatism, shaped by years of draining warfare and imperial overreach. UCLA’s MANAS resource highlights how opportunities for grand architectural projects dwindled under his reign. This austerity shapes the Maqbara’s character; it feels less like a testament to unrestrained love and more like a functional monument shaped by necessity.

Today, Bibi Ka Maqbara is celebrated as a treasured landmark, proudly known as the “Taj of the Deccan.” Protected by the Archaeological Survey of India, it draws visitors to Aurangabad, complementing the nearby Ellora and Ajanta caves as a cultural constellation. And its story of love on a budget offers a resonant counterpoint to the Taj’s perfection, reminding us that devotion need not always wear the guise of extravagance.

Preservation efforts throughout the 20th century have sought to maintain its charm and structural integrity, even as it endures inevitable comparisons. While not yet a UNESCO World Heritage Site, its tentative inclusion underlines the diverse architectural heritage of the Mughal era.